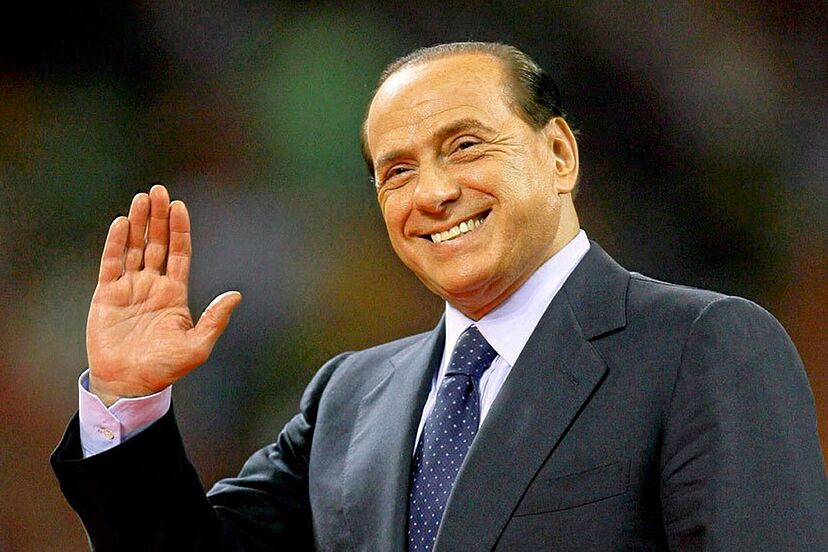

MILAN, (Reuters) – Silvio Berlusconi, the billionaire media mogul and former Italian prime minister who transformed the nation’s politics with polarising policies and often alarmed his allies with his brazen remarks, died today aged 86.

Berlusconi, Italy’s longest-serving premier who counted Russian President Vladimir Putin as a friend and gained notoriety for his “bunga bunga” sex parties, had suffered from leukaemia and recently developed a lung infection.

He died at Milan’s San Raffaele hospital, where he had been since Friday, at around 0730 GMT. Four of his five children and his brother Paolo had been at his bedside, ANSA reported shortly before his death was announced.

Berlusconi’s Forza Italia party is part of Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s right-wing coalition, and although he himself did not have a role in government, his death is likely to destabilise Italian politics in the coming months.

His business empire also faces an uncertain future. He never publicly indicated who would take full charge of his MFE MFEB.MI company following his death, even though his eldest daughter Marina is expected to play a prominent role.

His passing was mourned by allies and rivals alike.

“We fought, won, lost many battles with him, and also for him we will bring home the goals that we had jointly set ourselves. Farewell Silvio,” Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni said.

Enrico Letta, a former center-left premier, wrote on Twitter: “Berlusconi made the history of our country. His death marks one of those moments in which everyone, whether or not they backed his choices, feel affected.”

Shares in MFE’s A- and B-shares jumped by as much as 10% after Berlusconi’s death was reported, with traders on the Milan bourse saying it could pave the way for the company to be sold or merged with a rival.

After building a television empire in the 1980s, Berlusconi threw himself into politics in 1994 and almost immediately became prime minister. He held the post four times – 1994-5, 2001-5, 2005-6 and 2008-11 – despite multiple legal scandals.

He stepped down as prime minister for the last time in 2011, with Italy close to a Greek-style debt crisis and his own reputation sullied by allegations that he had hosted “bunga bunga” sex parties with underage women, something he denied.

He was acquitted on appeal on all charges related to the parties, but he was convicted for tax fraud in 2013, leading to a five-year ban on holding public office.

Despite his health woes and the relentless court battles, Berlusconi refused to relinquish control of Forza Italia and returned to frontline politics, winning a seat in the European Parliament in 2019 and in the Italian Senate last year.

While presenting himself as an elder statesman, he continued to fuel controversy, most notably with his refusal to blame his old friend Putin for the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, saying Moscow had only wanted to put “decent people” in charge of Kyiv.

There is no obvious successor to take the reins at Forza Italia, which won 8% of the vote in 2022, and allies and foes will want to poach his loyal electorate, who stuck with Berlusconi through thick and thin.

Perennially suntanned and vigorously promoted by his own media companies, Berlusconi brought his great skills as a salesman and communicator to the staid world of politics, offering a bright, optimistic outlook that voters lapped up.

He also had a sense of humour that often landed him in trouble, most recently last December when he told players of his Monza soccer team the would bring them “a bus of whores” if they managed to beat a top Serie A rival.