By Carl B. Greenidge

The name Havelock Brewster undoubtedly should feature among those who helped to put Caribbean economic scholarship on the academic map.

In the early 1960s the workings of the global economic system and of world trade seemed to condemn developing states to perpetual poverty. In the search for a more convincing explanation of the mechanisms involved, economists turned to analytical frameworks beyond those of the classical school even as exemplified by the pioneering contribution of the venerable W A Lewis, Nobel Prize winner, for example. In the process, they turned to more radical and robust frameworks of analysis including Marxist economic analysis. In Latin America a Dependency School emerged which contended that underdevelopment or economic backwardness was the result of dependence and that the dependence was the product of the specific financial and institutional relationships between the periphery (and the LA region in particular) and the metropole. In the Caribbean, ‘The New World School of Economics’, following only partly in the footsteps of the work of the Caribbean’s own venerable Sir W Arthur Lewis and William Demas, set out to fashion a framework as well as a comprehensive programme of regional economic transformation relevant to the Caribbean and its small states. The members of that school included a core of economists such as Lloyd Best (with Kari Levitt) George Beckford and Alister McIntyre based at the University of the West Indies.

Havelock Brewster in collaboration with Clive Thomas in, ‘The Dynamics of West Indian Economic Integration” (Mona, Jamaica: Institute of Social and Economic Research, 1967), led the charge in setting out what was to become a seminal work and one of the best known pillars of that programme of transformation. (See for example, Richard Bernal et al, 1984. Caribbean Economic Thought: The Critical Tradition. Social and Economic Studies. Vol. 33, No. 2, The Social Sciences and Caribbean Society (Part 2, June.).

They identified international trade as a major constraint on the rate and direction of development of small states and proposed regional integration as a solution to overcome the handicaps of small size and diseconomies of scale. That publication marked a major departure in the analysis of economic integration and development policy pertaining to small states.

Brewster, the co-author evolved into one of the most accomplished economists produced by the Caribbean region. He undertook substantial studies in a number of topical areas, including prices and wages, productivity, planning and the use of input output analysis. In these he matched analytical capacity with strong quantitative skills and an ability to persuade. After his notable contributions to the New World School of Caribbean Economics his preferment as Professor of Economics at UWI Barbados Campus followed in 1971-3.

He subsequently opted to leave the academy for UNCTAD in Geneva where he was to spend much of his professional life. From there and wherever he was located, he would undertake forays to contribute to deliberations on subjects of importance and interest especially in international trade, development and the like. UNCTAD had for many years been the premier multilateral institution in the field of development for which it had a mandate especially given the inability of the UN members to establish the International Trade Organisation as envisaged in the post-War global economic management architecture. UNCTAD sought to assist the developing countries to participate in world trade by improving market access abroad, strengthening and stabilizing commodity markets and enlarging financial flows to them. It had established a reputation for faithful pursuit of that goal particularly under Directors General, Raul Prebisch and F.H Cardoso. In the words of the Secretariat (UNCTAD: A brief historical overview., UNCTAD Secretariat, 2016), ‘Even for close observers of multilateral development diplomacy, the overall perception people hold of UNCTAD seems to be that, in its heyday, it was a vigorous advocate for radical structural changes in the international economic regime, but that this period has long passed and that it was pointless to examine its current activities.’ Even after the heyday to which the foregoing assessment makes reference, UNCTAD served as a kind of think tank. It provided technical assistance to Guyana, for example during the latter’s struggle to formulate and implement an effective response to the economic crisis of the mid 1980s. Over the period 1988-1992 when Guyana was involved in negotiating the Paris Club debt rescheduling Agreements, various Structural Adjustment Agreements with the Bretton Woods Agencies, IBRD and IMF and the IDB, within the framework of the Economic Recovery Programme (ERP) the willing assistance of UNCTAD as an independent and philosophically understanding agency was invaluable in the successful achievement of Guyana’s goals.

At UNCTAD, Brewster advanced up rungs of the organization and in April 1982 he was appointed as Chief or Head of the critically important Commodities Division. From that vantage point he led UNCTAD’s widely recognized work on trade analysis and global investment including the role of Foreign Direct Investment. In deciding to go to UNCTAD, Brewster may well have anticipated, not unreasonably, that in the Secretariat he would be strategically placed to gain a clear view of, and be in a position to influence, international policy-making and development. However, the institution had powerful enemies, many of those were driven by the fear of the very potential that Brewster and developing country economists and policy-makers posed.

He was subsequently joined in the institution by his former colleague from the New World Group, Sir Alister McIntyre, who with the support of the region was appointed as the DSG. Brewster was re-assigned by Sir Alister, as part of a ‘restructuring’ exercise involving some 39 staff members when Sir Alister became Officer-in-Charge, in June 1985. Not all observers accepted this change in good faith least of all Brewster. He saw it as a personal attack and some sections of the press concurred and claimed that it may have been taken in response to the demands of a few member states. The details of the case are not germane here but it is mentioned to highlight two issues confirmed by the UNCTAD tribunal which looked into Brewster’s formal complaint about the matter. First, there was Brewster’s ‘outstanding’ contribution to the institution’s work and his versatility as a technician. This complaint which remained unresolved for over two years points to the tendency, common in the region, for intellectual and personal rivalries between outstanding Caribbean personalities get out of hand and become dysfunctional. Brewster concluded his career at UNCTAD as Special Research Advisor, probably specially created in recognition of his contribution to the institution’s standing in international trade. He was one of a select band of Guyanese who reached the top or penultimate tier of a multilateral or plurilateral economic institution. That select band includes Kenneth King (FAO), Maurice Odle (UN Centre for Transnational Studies), Carl B Greenidge (ACP) and P I Gomes (ACP).

Ironically, Wikipedia, under the topic ‘Guyanese economists’, lists the names of three individuals, (C Y Thomas, Winston Jordan and Vishnu Persaud) not including Brewster https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Guyanese_economists). This is as much a testimony to the inadequacy or inappropriateness of Wikipedia’s approach to identifying material. It may also be a reflection of Guyana’s lack of recognition of its own scholarship and if outstanding practitioners of the discipline, such as Profs Rawle Farley and Kerwin Charles do not merit a mention on such pages we ought not to regard the omission of Prof Havelock Brewster as an outrage. He did, however, shine both as an international civil servant and as an academic. He has also published widely.

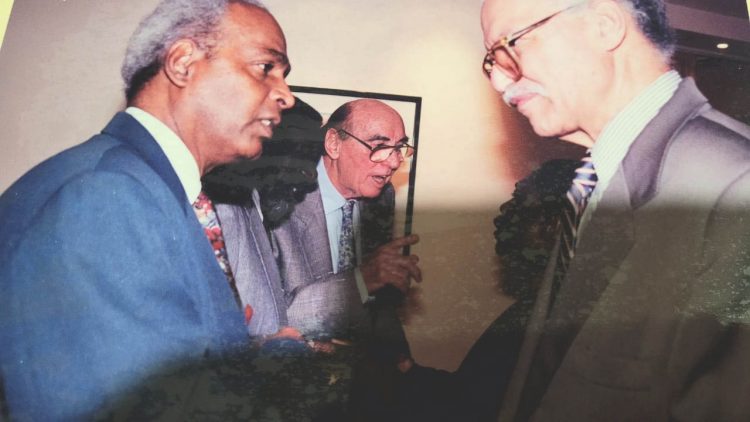

When I first met Brewster in 1989, he was already well established as an economist of international repute. We met in Geneva. I was contributing a paper to a UN Conference on Privatisation of Public Enterprises. He was not a participant but in our conversations and in his public delivery it was impossible to miss the impression that he projected a great degree of gravitas. For all that, he was approachable and a very friendly person. Over the years following our first meeting he found time for social encounters, including at his home to exchange ideas and welcome those he found interesting especially during his diplomatic stints in Brussels and Washington.

On one occasion in Geneva in 1991 he confided in me that he had been approached by Dr Jagan to take up the position of Economic Adviser to the PPP leader and the PPP. We discussed some of the hazards and pitfalls of such an assignment in the very difficult political climate of Guyana. He eventually took up the offer from the Guyana leader and evidently became a close and trusted adviser to the President whom he almost invariably accompanied to international and bilateral meetings; even when he served as Guyana’s AED and Executive Director (ED) to the IADB in the first decade of the millennium and as Advisor to the CRNM. Subsequently, he was appointed as Ambassador to the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the EU. He remained a close and influential adviser to the PPP and Dr Jagan until the latter’s demise. In 2008 and 2009 he emerged briefly, from what may have been exile or a period of quiet reflection, on the side of the NGOs and Caribbean academia to join the public debate on the signing of, and contested necessity for the Caribbean Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) in the Context of the ACP-EU Cotonou Accord.

In all the period I knew Havelock Brewster (Ross-Brewster) he clearly enjoyed his position as a recognized, front-line economist but I also had the impression that he and his family very much enjoyed the postings to Washington and Brussels. He was a strong ‘family man’ and seemed to find refuge and to derive much strength from the family. The manner and timing of his wife, Jennifer’s demise was therefore particularly poignant and shocking for him. On their very final day (or final day of packing) in Brussels Jennifer Ann suddenly collapsed and died. I am of the impression that he never fully recovered from the manner of the loss.

Havelock Brewster enjoyed the limelight as an economist. His interests were not restricted to that arena however. He had a longstanding interest in philosophy, science and literature along with facility in French and Spanish. The latter could partly explain why he may have been so comfortable in Belgium.

Prior to making his mark as an economist Brewster read for a first degree in economics at the University of Durham, in the United Kingdom, and followed this with a MA in Economics from Dalhousie University, Canada, in 1964 where he also won a post-graduate Fellowship.

Brewster’s standing and friendships among the UWI colleagues, where he was appointed an Honorary Professor of Economics at the ISER, remains very high. At the time of his demise he was one of the giants of Caribbean economics as well as one of most able public servants we have contributed to the international fora. He leaves us, having played his part in ensuring that regional analysis with a Caribbean flavour had a respected voice in the corridors of international and regional policy making. At the latter level, that voice, although heard and accepted, has elicited only a fitful policy response largely evident in lip service rather than in meaningful sustained action. That struggle to ensure that Caribbean political leaders keep regional integration, the Single Market and Economy in particular, on the front burner is still a work in progress (See Odle, for one insight into the evolution of this idea, in ‘Caribbean Integration: is the glass half full or half empty?’. The CLR James Journal 21-2. P87-94. Fall 2016).