The topic of de-dollarization is all over the popular press these days. Some have been predicting the demise of the American dollar for decades, while others have taken the enlightened view that the world will be a better place if international payments are settled in a multipolar currency framework, involving about four or five dominant currencies. Perhaps the recent prognostications of the dollar’s demise stem from the American government’s (Trump and Biden administrations) overuse of sanctions following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, as well as the ripping up of the Trans-Pacific Partnership by the Trump administration.

Interestingly, before the recent heightened interest in de-dollarization, academics and policy makers have long pondered the idea of dollarization, a situation in which the American dollar gradually replaces (or encroaches on various functions of) a country’s national currency. I will first discuss my thoughts about de-dollarization in this column and the next one, where I specifically discuss the topic of the Chinese currency and euro versus the dollar. The column after the latter will explore the old topic of dollarization by outlining several pros and cons.

The dollar serves several international purposes that became locked in from the formation of the Bretton Woods in 1945 and the fact that the United States became the largest economy much earlier. When Bretton Woods – a system of direct and indirect pegged exchange rates against gold – collapsed in 1971, the dollar was already privileged as a global currency for settling international payments. It made sense because the US economy exceeded that of the United Kingdom around 1918. A new system of fiat currencies was ratified in 1973 to replace the Bretton Woods pegged exchange rate system. Under the fiat money system, currencies will trade freely against each other in world markets. Some nations such as the small economies in the Caribbean, several in Africa, and notably China decided not to have freely floating rates, instead their central banks continually intervene to maintain a fixed rate or a managed rate around a desired objective (target).

A first major function of the dollar is it provides an international store of value, meaning that countries save their foreign exchange (FX) reserves in dollar-denominated assets, typically safe U.S. government treasury bills and bonds. Recall, countries hold FX reserves for various reasons such as for precaution, import cover requirements, exchange rate management and other factors. As noted in my previous columns, the Bank of Guyana manages this country’s FX reserves, which must be separate and distinct from the dollars held in the Natural Resource Fund (NRF). I have written in the past that when the government draws down from the NRF, it is expanding the Guyanese money supply once the central bank purchases the dollars.

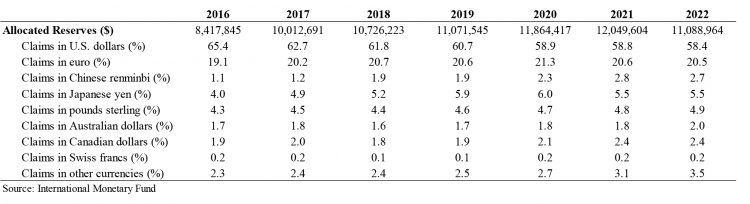

The table provided outlines the total amount of FX reserves countries have reported to the IMF, which then compiles the composition in various national currencies. It is clear that the dollar has lost some ground, about 7 percentage points in recent years. Meanwhile, the Chinese renminbi has increased its share from 1.1% in 2016 to 2.7% in 2022, gaining 1.6 percentage points of the dollar’s loss. However, the dollar is still the most dominant reserve currency, assuming 58.4% of allocated reserves in 2022.

Over the period 2016 to 2022, the euro’s share has remained remarkably stable, prompting one to ask why is this the case? Why has the euro failed to win a share of what the dollar lost since 2016? I will provide an answer in the next column why the euro is unlikely to move significantly beyond this share of global reserves.

The Japanese yen has increased its share from 4% of allocated reserves in 2016 to 5.5% in 2022. This is interesting when one considers that Japan has the highest sovereign debt to GDP ratio among developed economies. In spite of all the problems in the United Kingdom related to energy insecurity and Brexit, that country preserved and gained a share of global allocated reserves, perhaps testimony to financial path dependence (financial history), strong property rights and democracy.

A second important global role of the dollar is it serves as a vehicle currency. This means that the dollar shows up on at least one side of most foreign exchange transactions in the global markets. For example, if a Guyanese wants to trade foreign exchange with a Barbadian, he/she will find that there is not an active market for Bajan versus Guyana dollars. However, an easy trade is to find a vehicle currency (the dollar) against which each currency can be exchanged.

According to data from the Bank for International Settlements, the dollar’s share as a vehicle currency rose from 2010 to 2022, while the euro’s and yen’s share declined. The British pound kept its share as a vehicle. The Chinese renminbi realized a 7% increase in its share from 2010 to 2022, but its overall share, similar to its share in international reserves, remains small relative to that of the dollar. Moreover, data from another source indicates that the dollar accounts for 95% of all SWIFT transactions as at first quarter of 2023.

A contemporary example will emphasize the importance of a liquid vehicle currency and the financial dilemma BRICS will face as it ponders a new currency. A lot has been made of India’s purchase of Russian oil since the Ukraine war. Given that Russia has adopted a boycott policy with respect to the dollar, it wants payments in its own currency: the ruble. Therefore, Russia has amassed billions of rupees in Indian banks. Without the dollar, India is finding it difficult to exchange its rupees for rubles in order to pay Russia. If Russia insists on ruble-rupee transactions, then it will have to assume a steep discount because of transaction costs associated with payments in rubles. The dollar, on the other hand, is generally acceptable for global payments – hence, it is a lot more liquid with none of the transaction costs associated with ruble-rupee payments. As of today, India is clearly the unintended winner in this scenario.

The dollar has another important role in the global economy: it is the most dominant invoicing currency. Most countries invoice their exports and imports in dollars. The invoicing role is obviously tied up with the vehicle role of a currency. In its most simple form, when someone buys a plane ticket to Guyana or a hotel room in Barbados, he or she will notice that these services are priced in dollars; Guyanese exporters earn dollars, not Guyana dollars. If folks are interested, they can download our recently accepted paper: “Dominant currency shocks and foreign exchange pressure in the periphery,” where we present the data for 13 economies, including several large emerging market economies.

We do not, however, know the invoicing data for Guyana and the small economies of the Caribbean. Nonetheless, I am willing to bet my Toyota Prius that Guyana invoices more than 96% of its exports and imports in dollars. Textbook theories of the exchange rate and conventional ideas like Marshall-Lerner are no longer applicable to our situation when we account for invoicing of exports and imports in a major global currency. This practice also requires that we fundamentally rethink how monetary and exchange rate policies work. Suffice to say, the old justification for currency devaluations and depreciation have to be thrown out of the window. It simply does not work in stimulating exports and competitiveness. As a matter of fact, a depreciation can do the opposite by worsening competitiveness via the distribution of income.

In the next column, I will explain my perspective why the euro and yuan will not be a serious threat to the dollar and why the dollar is likely to regain its share of 66% of FX reserves in the coming years.

Comments: [email protected]