The Petroleum Activities Bill 2023

The Petroleum Activities Bill 2023

On 20 June 2023, the Ministry of Natural Resources released the draft Petroleum Activities Bill 2023 for public comment, with a 14-day period for doing so. Considering the importance of having a modern and up-to-date legislation for the oil and gas sector, this is too short a period for a comprehensive review to be carried out of the Bill. Additionally, if passed into law, the Bill will replace the Petroleum (Exploration and Production) Act of 1986 which was promulgated at a time when there was no evidence of discovery of petroleum products in commercial quantities. We trust that the Authorities will see it fit to extend the deadline for comment by at least another 14 days.

In today’s article, we begin a discussion of the contents of the Petroleum Activities Bill 2023 whose main purpose is to provide for exploration, production, storage, and transportation of petroleum via pipelines and to incorporate rights over subsoil geological pore space.

The IMF’s assessment of the 1986 Act

In its 2017 report entitled “Guyana: A reform Agenda for Petroleum Taxation and Revenue Management”, the IMF identified several deficiencies in the 1986 Act. These include:

(a) The discretional nature of the fiscal provisions, such as royalty payments, profit sharing and taxation, leaving the specifics to be dealt within the various Production Sharing Agreements (PSAs) entered into with oil exploration companies;

(b) The Minister responsible for petroleum, in consultation with the Minister of Finance, having the authority to remit, in whole or in part, any royalty payable, upon application by a licence holder, or to defer payment; and

(c) The Minister having discretionary powers to exempt a licensee from income tax, corporation tax and property taxes, among others, subject to affirmative resolution of the National Assembly

According to the IMF, most PSAs around the world usually have a formula in which the government’s share increases as a function of production, a combination of production and prices, or an economic variable such as the ratio of cumulative revenue to cumulative costs, or the project’s internal rate of return. In many countries, the top tier government share of profit oil could be as high as 80 or 90 percent. The Fund also expressed concern that although the Act provides for competitive bidding procedures to be followed in the grant of petroleum prospecting licences, the practice has been to grant such licences and to negotiate PSAs on a first-come-first-served basis. In addition, while the Act provides for the grant of petroleum prospecting and production licences, it is mostly silent on processing and refining of petroleum products and other associated activities. Accordingly, the IMF recommended that the Authorities consider reforming and modernizing the legal and fiscal framework for petroleum exploration and production.

Structure of the Bill

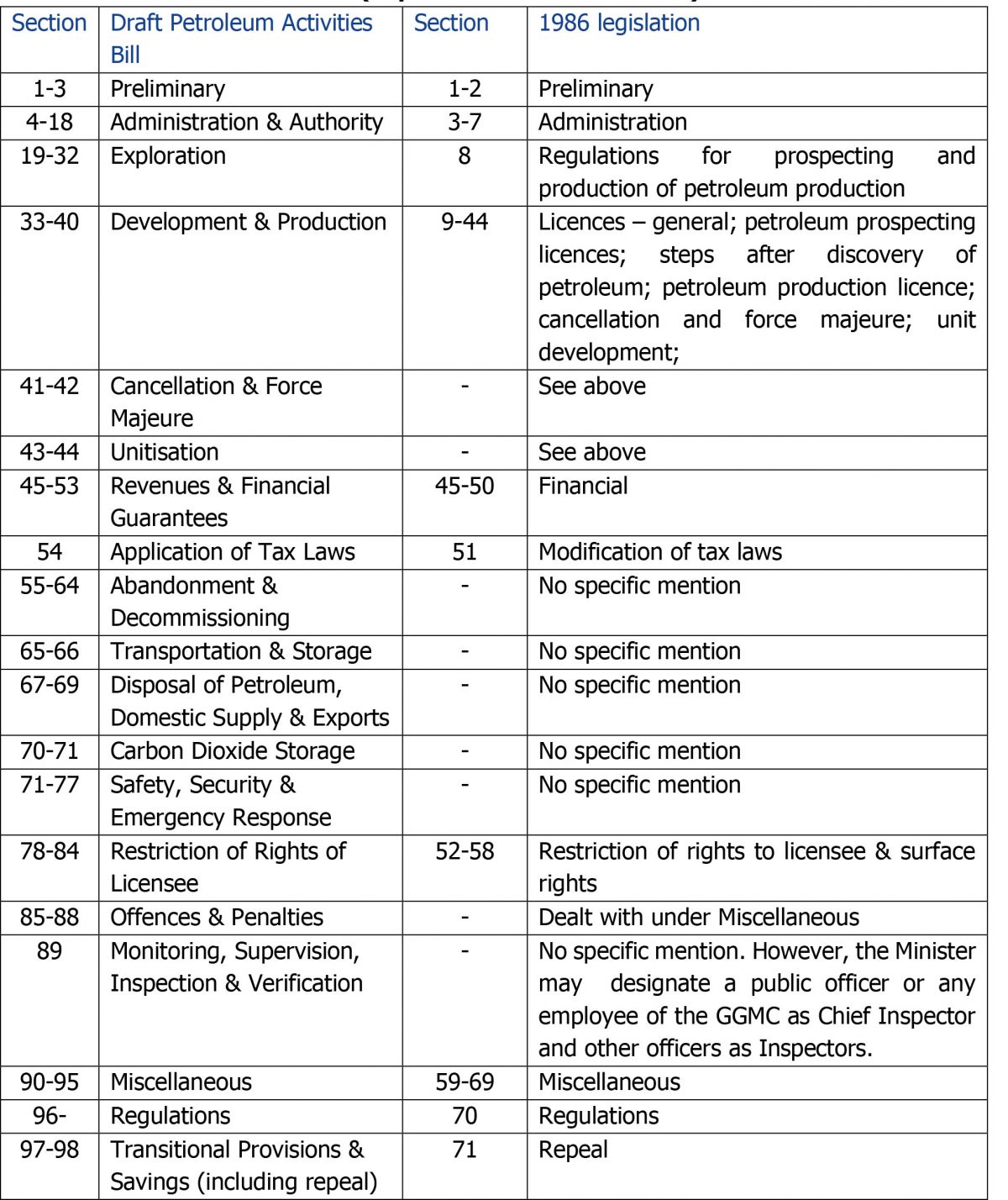

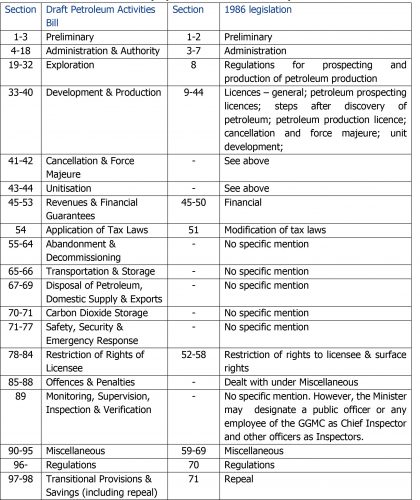

The Petroleum Activities Bill contains 56 pages covering 98 sections, compared with the 1986 Act that has 51 pages and organized in 79 sections. On the face of it, the Bill appears more comprehensive than the 1986 Act. Table I provides a comparison of structure of the Bill with that of the 1986 Act.

Table I

Comparison of the structure of the Petroleum Activities Bill with

the Petroleum (Exploration and Production) Act 1986

Part I – Preliminary

The Bill applies to the exploration, production, storage, and transportation of petroleum via pipeline and the geological storage of natural gas and carbon dioxide in the national territory including the internal waters and territorial sea, as well as in the contiguous zone, the exclusive economic zone, and the continental shelf. It also applies to utilisation of produced petroleum when such utilisation is necessary to or constitutes an integral part of production or transportation of petroleum. Additionally, the Minister may issue regulations to supplement or delimit the provisions of this section about what utilisation is considered necessary to or constitutes an integral part of production or transportation of petroleum.

In comparison, the 1986 Act applies to not only exploration and exploitation of petroleum but also its conservation and management. Given the importance of conservation in the light of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, it is unclear why this specific requirement has not found its way in the Bill.

Part II – Administration and Authority

The Bill provides for property rights to be vested in the State, covering the pore space of sub-soil or sub-seabed geological formations and petroleum existing in its natural condition in strata underlying the national territory including the internal waters and territorial sea, as well as in the contiguous zone, continental shelf, continental margin and the exclusive economic zone,. The 1986 Act makes no mention of this, which therefore represents an improvement.

Under Section 5, the Minister has extensive responsibility in the administration and management of the petroleum sector. This includes:

(a) Ensuring responsible exploration, development and utilization of natural resources;

(b) Protecting and conserving the environment and advancing the low carbon economy;

(c) Ensuring the development of petroleum resources is economically sustainable, promotes investment and contributes to the economic development of the nation and long-term benefit of the people of Guyana;

(d) Creating a stable, competitive and predictable regulatory environment;

(e) Ensuring the optimization of infrastructure to minimize the footprint of petroleum operations;

(f) Seeking deployment of proven and commercially viable clean technologies to reduce the carbon intensity of petroleum operations to as low as reasonably and commercially practicable; and

(g) Ensuring petroleum operations comply with applicable law and best international industry standards and practices.

Additionally, Section 6 confers upon the Minister the following powers:

(a) Administering licensing of petroleum exploration, production, storage and transportation operations;

(b) Prescribing rules, regulations and issuing guidance as is necessary to carry out the purpose of the Act;

(c) Cooperating with the relevant government agencies regarding environmental and safety aspects of petroleum operations;

(d) Overseeing the conduct of petroleum operations to ensure compliance with the Act, and the terms of the respective licence and petroleum agreement;

(e) Inspecting petroleum operations and seeking corrective action and

imposing sanctions for non-compliance;

(f) Develop terms of reference and qualification criteria for the grant of exploration and production rights;

(g) Granting geological storage licences for natural gas and long-term storage of carbon dioxide; and

(h) Exercising any other powers required for the management of petroleum resources and operations carried out under this Act.

In contrast, the 1986 Act provides for the Minister to designate a public officer or any employee of the Guyana Geology and Mines Commission (GGMC) as Chief Inspector for the purposes of the Act as well as such number of public officers or employees of the Commission as are considered necessary, as Inspectors. However, while the Bill makes no specific mention of the involvement of the GGMC, the Minister may delegate any of the powers related to administration of petroleum resources and supervision and inspection of petroleum operations to a department, agency or government body under its administrative authority.

It is evident that the Bill provides for an over-concentration of powers in the hands of the hands of the Minister. It will be recalled that the Petroleum Commission Bill was tabled in the Assembly in 2017, providing for the establishment a Petroleum Commission to oversee and manage the oil and gas industry to ensure, among others, compliance with the policies, laws and agreements relating to petroleum operations, including compliance with health, safety and environmental standards as well as local content and participation requirements. It was also to be responsible for researching efficient, safe, effective and environmentally responsible exploration, development and production of petroleum in Guyana, including the optimum methods of exploring and extracting petroleum and petroleum products.

The Commission was to act as an advisory body to the Minister, while the board of directors was to comprise experts in various fields as well as representatives of civil society and the parliamentary opposition.

The Petroleum Commission Bill was referred to a Special Select Committee of the National Assembly for detailed consideration but did not make it back to the Assembly for debate and approval. In September 2020, the Minister indicated that the Bill would be re-tabled within six months. To date, this has not been done. The main concern was about the elaborate powers vested in the Minister, a concern that the then Minister of Natural Resources had acknowledged. In his inaugural speech on 8 August 2020, the President stated that there were plans to set up a Petroleum Commission to insulate the oil and gas sector from political interference. And as recent as last week, the Vice President indicated that the establishment of the Commission is not a priority at the moment. He sought to justify the over-involvement of the Minister on the ground that no Commission is in place.

Given the over-concentration of responsibilities and powers in the hands of the Minister, we urge the Authorities to establish the Petroleum Commission first and then to make the necessary amendments to the Petroleum Activities Bill so as to transfer some of the responsibilities and powers to the Commission.

– To be continued –