Denis Williams (1923 – 1998) received the first-ever British Council Scholarship granted to an artist from British Guiana in 1945. While it has been recorded posthumously from the recollections of a much younger contemporary that Williams received this award for the skill exhibited in Portrait of Peter (see a reproduction with last week’s article), I believe that Self-Portrait with a Towel was a more likely contender.

Denis Williams (1923 – 1998) received the first-ever British Council Scholarship granted to an artist from British Guiana in 1945. While it has been recorded posthumously from the recollections of a much younger contemporary that Williams received this award for the skill exhibited in Portrait of Peter (see a reproduction with last week’s article), I believe that Self-Portrait with a Towel was a more likely contender.

The latter was painted in 1945, the same year as the award, and demonstrates far superior skills than the former. With the latter, we see a superb understanding of the anatomy of the face, and both a psychological and aspirational presence of the sitter. This Williams painted in oil has ideas about himself that are not those of a colonial subject in subjection. The work, therefore, anticipates the kind of colonial subject Williams would become – one willing to gently and robustly fray the tethers of coloniality. Self-portrait with a Towel was coincidentally the work meditated upon by a young Arlington Weithers which he used to train his eyes (see Eye on Art May 21, 2023). This work Weithers spoke of now identified was not painted while Williams was in Sudan, but seen by the younger relation years later while the older was off in the distant land.

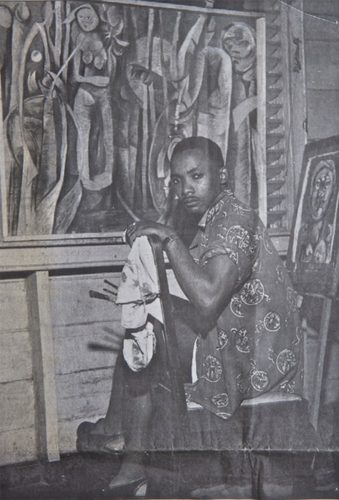

Denis Williams – Oil, 1945 (As reproduced in

The Daily Chronicle August 13, 1950)

Nonetheless, Williams, already a highly competent portraitist, embarked on his two-year course at Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts in 1946. Today the institution is one of six colleges within the body collectively referred to as the University of the Arts London. However, in 1946 Camberwell was an independent institution. At Camberwell, Williams was exposed to training that included studies of the full human anatomical form and drawing and painting from the model. This is noteworthy, as Williams and his British Guiana contemporaries in the 1940s appear to have had little opportunity to develop skills in these two areas of study as the visual records are overwhelmingly of landscapes. And while Williams was already evidently knowledgeable about the anatomy of the human face, portraits done by him in various textual records suggest this was not the case for the shoulders and upper torso and thus the full human body.

At Camberwell, Williams came under the instruction of influential British artists Claude Rogers, William Coldstream, and Lawrence Gowing who each excelled at portraiture (while two also excelled in landscape and one also excelled in still-lifes). Williams, therefore, was poised to become a grand portraitist capable of the full-body variant. Williams completed his course in 1948. In 1949, Williams exhibited with Ghanaian artist Kofi Antubam (1922 – 1964) who had trained at Goldsmiths’ College, University of London (now Goldsmiths, University of London). It was this exhibition that garnered Williams the attention of writer, painter, and critic Wyndham Lewis (1882 – 1957). Lewis was also the founder of Vorticism in 1914, a modern art movement that combined elements of Cubism’s fragmentary treatment of the environment with hard-edge abstraction. So favoured by Lewis was Williams that when Williams departed London for Georgetown in 1949 and as he was transiting through New York City, Lewis wrote letters of introduction for Williams to the Director of Museums Collections at the Museum of Modern Art, New York Alfred H Barr Jr; art historian and art collector James Thrall Soby; and University of St Louis Professor Felix Giovanelli who had connections to the art world.

In his letter to Barr Jr, Lewis wrote: “I am writing you this letter because (1) I regard him as a young man of very unusual talent: [sic] and (2) it is obvious that that talent will be wasted unless he can somehow, at this juncture, arrange his life in such a way as to enable him to paint […]” (Eve Williams, The Art of Denis Williams, p. 20). In his letter to Giovanelli, Lewis wrote: “Denis Williams is an extremely intelligent young man […]. Guiana is no place in which to be a painter. It would be wonderful if he could stay in New York […] The main fact in all this is that he is a very unusually talented artist” (Eve Williams, The Art of Denis Williams, p. 21). Unfortunately for Williams, neither Barr Jr nor Soby was in New York at the time of his visit and Giovanelli, despite his efforts, was unsuccessful in securing him a necessary extension to his visa or sponsorship to extend his stay. Ultimately, Williams’s race worked against him. In London, he was an anomaly among “Negro” men, and in New York, there was no room for multiple “Negro” artists. Thus, the reductive and pejorative attitudes that pertained to Williams’s race were prevailing, making working within the centres with ease an impossibility. Years later his countryman, Frank Bowling would reject a race marker in being categorised. Bowling rejected being defined as a Black artist and encouraged others to do the same so that their work could be looked at through lenses not blurred by denigrating racialized attitudes. Unfortunately for Williams, Georgetown was also a hostile place. For an artist returning home fresh from the feeding grounds of two centres of art – London and New York – Georgetown was not a place of welcome. In 1949, he exhibited a series of paintings with the Guianese Art Group, with which he had exhibited prior to his 1946 departure for London. The critical response was unwelcoming and has been reported on by Williams and others.

Of that experience, Williams in Kaie in 1976 in defence of the 1763 Monument noted that within a few months of his return home in 1949, he had completed a group of paintings he called The Plantation Series and that when exhibited, “They were instantly denounced. Concerning one in particular, Origins, [sic] a local newspaper informed the public that precious scholarship money had been wasted on a man who only wished to take Guyanese back to Africa.”

Williams initially left Guyana as a portrait artist of high repute and returned as some kind of rebel, painting the foundational ill of colonial existence – an entanglement of sugarcane and black bodies. Admitting his rebellious intentions, Williams also wrote in the aforementioned essay, “[The] last thing a colonial art-student returning to his country in 1948 would be thinking about would be [upholding] the classical tradition in which he was trained.” Rightly so. By 1948, European painters had already abandoned the Greco-Roman tradition and had assimilated lessons learned from Japanese woodcuts, Freudian theory regarding the dream and the unconscious, and aesthetic sensibilities inherent in West African sculpture. Thus, to return home doing as he had before his departure could have been seen as a waste of a scholarship and would have signalled that the sojourn away had not fuelled the flames of the aspiring colonial subject. In the face of Georgetown’s unreceptive public and thus clear indications of his artistic inclinations being suffocated, Williams departed once more for London. The May 2, 1950, issue of The Daily Chronicle carried on its front page amidst news of May Day parades, and news from Germany, Japan, and the United States, “B G artist to live in England.” The article announced that on the previous day, Williams had departed the colony on the Lady Nelson to Trinidad where he would embark the SS Misr to England. It also announced that Williams carried with him some paintings while others had been sent to New York in hopes of a show.

Continued next week.

Akima McPherson is a multimedia artist, art

historian, and educator.