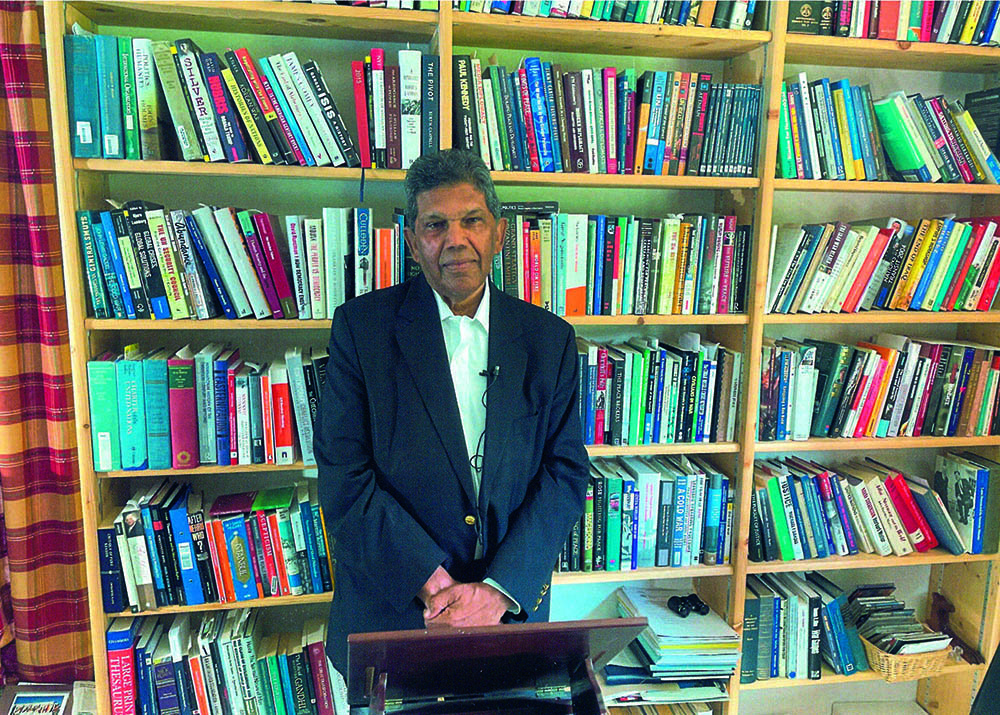

By Dr Bertrand Ramcharan

Seventh Chancellor of the University of Guyana; Previously Professor at the Geneva Graduate Institute. Sometime Fellow of Harvard University and Fellow of the LSE

With its history and demography, Guyana needs to strive continuously for the achievement of equality, and its government has to be seen to be doing this. Policy and perception are both important.

Thomas Piketty, a world-renowned French professor of economics, has just summarised his extensive body of writings into a concise volume, A Brief History of Equality, published by Harvard University Press in 2022. It is widely acclaimed for its insights on problems of inequality.

Since the end of the eighteenth century, Piketty writes, there has been a long-term global trend toward equality, but it remains limited in scope. Various inequalities have persisted, at considerable and unjustified levels, affecting issues such as status, property, power, income, gender, and origin.

Inequality, Piketty submits, is first of all a social, historical and political construction: “All creations of wealth in history have issued from a collective process: they depend on the international division of labour, the use of worldwide natural resources, and the accumulation of knowledge since the beginnings of humanity. Human societies constantly invent rules and institutions in order to structure themselves and to divide up wealth and power, but always on the basis of reversible political choices.”

In short, societies must discuss, agree upon, and pursue governmental policies calculated to promote equality. And in order to attain real equality, we must develop indicators and procedures that will allow us to fight gendered, social, and ethno-racial discrimination, which is, in practice, endemic nearly everywhere, in the global North as in the South.

Social class alone does not suffice to forge a theory of a just society, a theory of property, a theory of borders, of taxation, of education, of wages and salaries or of democracy. Struggles play a central role in the history of equality.

Educational equality is crucial. Historically, it has always been proclaimed but never realized: “The diffusion of knowledge has always been the central tool enabling real equality beyond origins”.

Since the end of the eighteenth century, efforts toward equality have been based on the development of a number of specific institutional arrangements that need to be kept under scrutiny: equality before the law; universal suffrage and parliamentary democracy; free and obligatory education; universal health insurance; progressive taxes on income, inheritance and property; joint management and labour law; freedom of the press; and international law.

However, all of these suffer from multiple insufficiencies and must be constantly rethought, supplemented, and replaced by others. As it currently exists almost everywhere, formal equality before the law does not exclude profound discrimination based on origins or gender. Representative democracy is only one of the imperfect forms of participation in politics. Inequalities of access to education and health care remain extremely intractable. Progressive taxes and redistribution of wealth must be completely reconceived on the domestic and international scale. Power-sharing in business enterprises is still in its infancy. Control of almost all the media by a few oligarchs can hardly be considered the most complete form of a free press. And the international legal system, founded on the uncontrolled circulation of capital, without any social or climatic objective, is usually related to a kind of neocolonialism that benefits the wealthiest people.

Resistance by elites, in the assessment of Piketty, is an ineluctable reality today, in a world in which transnational billionaires are richer than states. Questions regarding the organization of the welfare state, the recasting of the progressive income tax and international treaties, post-colonial reparations, and the struggle against discrimination are complex and technical and can be overcome only through a recourse to history, the diffusion of knowledge, deliberation, and confrontation among differing points of view.

The movement toward equality still has a long way to go, especially in a world in which the poorest, and particularly the poorest in the poorest countries, are being subjected, with increasing violence, to climatic and environmental damage caused by the richest peoples’ way of life.

In the course of the twenty-first century, the planet is probably heading for a temperature increase of at least three degrees.

The global North, despite a small population (about fifteen percent of world population for the United States, Canada, Europe, Russia and Japan) has produced nearly 80 percent of the carbon emissions that have accumulated since the beginning of the Industrial Age. For the period 2010 to 2018, of the one percent of the planet’s inhabitants who emit the most carbon, almost 60 percent resided in North America and their total emissions are higher than the combined emissions of the 50 percent of the planet’s inhabitants who emit the least. Most of the latter live in Sub-Saharan Africa and in South Asia.

Related to this, it is crucial to recognize that the general increase in population, production, and incomes, since the eighteenth century has taken place at the price of overexploiting the planet’s natural resources.

On present forecasts, the world population may stabilize at around eleven billion between now and the end of the century. In the face of this, “there is something totally insane about the very idea of perpetual and unidimensional growth, prolonged indefinitely over thousands and millions of years, and in any event it cannot constitute a reasonable objective for human progress.”

The march toward equality, Piketty assesses, is a battle whose outcome is uncertain, and not a road laid out in advance. Without resolute action seeking to drastically compress socio-economic inequalities, there is no solution to the environmental and climatic crisis.

Piketty advocates a model of cooperative development based on universal values and on objective, verifiable social and environmental indicators that make it possible to publicly state the extent to which different classes of income and wealth contribute to public and climate burdens. It is also necessary to describe precisely the transnational assemblies that would ideally be entrusted with global public goods and common policies of fiscal and environmental justice.

He avers: “In this book, I have defended the possibility of a democratic and federal socialism, decentralized and participatory, ecological and multicultural, based on the extension of the welfare state, progressive taxation, power sharing in business enterprises, postcolonial reparations, the battle against discrimination, educational equality, the carbon card, the gradual decommodification of the economy, guaranteed employment and an inheritance for all, the drastic reduction of monetary inequalities, and finally, an electoral and media system that cannot be controlled by money.”

He concludes that while human progress exists, the movement toward equality is a battle that can be won, but it is a battle whose outcome is uncertain, a fragile social and political process that is always ongoing and in question. Human progress never evolves ‘naturally’. It is subject to historical processes and specific social battles. The organization of the global economic system is still very hierarchical and inequitable. There is much work to be done globally for the advancement of equality.

And in Guyana, a practical start would be for Government and society to heed Piketty’s advice about equality in education. Educational equality, he emphasises, is crucial.

Historically, it has always been proclaimed but never realized: “The diffusion of knowledge has always been the central tool enabling real equality beyond origins”.

It would be a tangible test of the Dear Land’s commitment to equality if its newly-found resources would be used to achieve genuine equality in education.