In this week’s edition of In Search of West Indies Cricket, Roger Seymour presents the second part of the Mike Findlay interview. Part One, The Trailblazer was published last Sunday

On the morning of Saturday, 30th August 1997, I returned to the Pegasus Hotel to pick up Mike Findlay, who wished to go and pay his respects to the family of the late Hubert Cromarty, the Guyanese physiotherapist who had accompanied the West Indies team on their 1968/69 Tour of Australia and New Zealand. Findlay had fond memories “of the wonderful soul, who was always willing to render assistance.”

Findlay was having breakfast when I arrived, having just finished a workout in the gym. As soon as I sat down, he enquired if I had brought my notepad, since he had prepared some notes, wanting to add to his earlier thoughts, particularly on fitness and captaincy.

Fitness

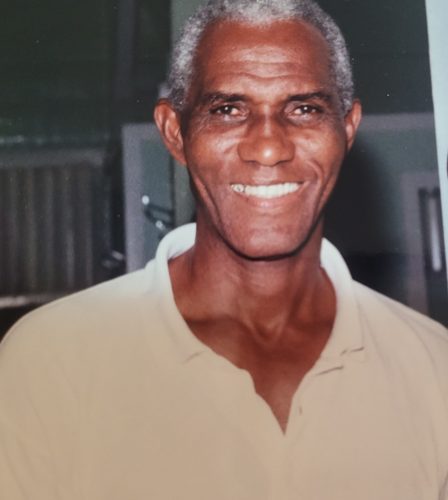

Tall and lanky, the 54-year-old Findlay readily discoursed on his fitness philosophy: “I have always worked on my fitness. Ever since my high school days, I have strived to be superbly fit by training hard. In addition to three weekly sessions at the gym, I stretch and do calisthenics on a daily basis. I still swim in the ocean, and do a lot of running in the sand at the beach. Apart from the odd glass of wine, I never drank.

“I have never stopped playing cricket. Last Sunday, I played for my club, Saints, in the National Knockout Championships. Saints has been the only club I have played for, and I have represented it in the Premier Division since 1962. It’s one regret I have in the Caribbean, that too many chaps stop playing between the ages of 35 and 40, and they have so much knowledge and experience to share and pass on.”

It was an interesting observation; a wealth of untapped knowledge just sitting there. Basil Butcher of the Mackenzie Sports Club in Linden, and Seymour Nurse of Spartan in Barbados, are the only players that readily spring to mind, who continued to play long after their time at the top was over.

Captaincy

Findlay was well versed in the role of leadership. He had been prepared for it from his earliest days of representing Troumaca Village – where anyone could have been called upon at any time to address the team – through his sojourn at the St Vincent Grammar School, where he skippered both the cricket and football teams.

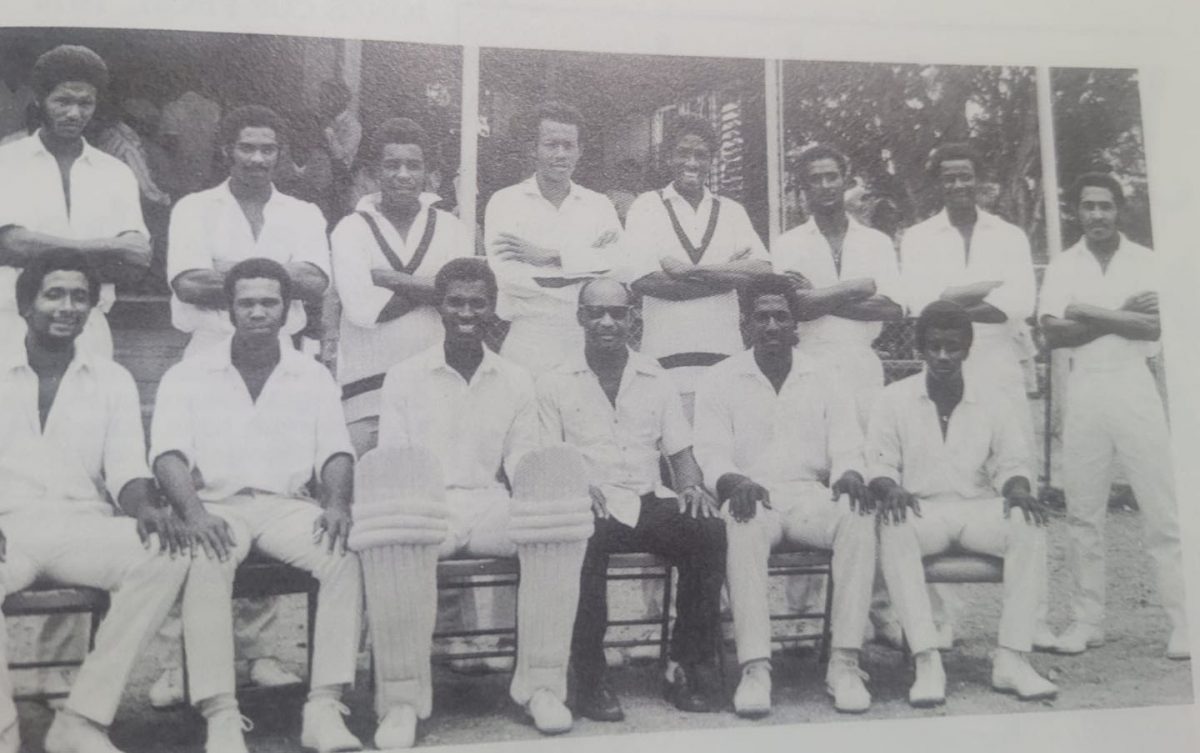

In 1970, Findlay, the newly-crowned West Indian Test custodian was given the honour of leading the Combined Islands. It was not an easy task, since there was not much interaction between the two chains, and there were also fierce rivalries within each archipelago. The Combined Islands, with a brittle batting line up, further coupled with limited preparation time and poor training facilities, lost all four of their matches outright. The wooden spoon was a harsh baptism for the new captain at the first class level.

In 1971 and 1972, Findlay led a youthful St Vincent and the Grenadines team to the Bottlers Trophy in the annual Windward Islands Competition, thus breaking the hold on the tournament by the Dominicans, led by the Shillingford clan. In 1972, under his leadership, St Vincent made a clean sweep with outright wins over Dominica, St Lucia and Grenada. In 1973, St Vincent and Dominica shared the title as Findlay, leading the way with his bat, scored 234 runs at an average of 58.50, including an innings of 112 versus Grenada.

In 1974, after one season of Leonard Harris’ captaincy, and two under the guidance of Irvine

Shillingford, Findlay was again handed the honour of leading the Combined Islands, whose best finish in the competition was fourth the previous year. Despite the development of young players such as Andy Roberts, Jim Allen, Viv Richards, Victor Eddy blended with the Test capped Findlay, Grayson

Shillingford and Elquemedo Willett, and the experienced Irvine Shillingford, the team from the ‘small

islands’ finished in the cellar once again, as their batting failed to deliver substantial scores.

Almost 50 years later, the 1975 Shell Shield Tournament is safely ensconced in West Indies

cricket folklore, following the furore over the official decision of the famous ‘Tanti Merle’ match at the

Queen’s Park Oval between the Combined Islands and Trinidad and Tobago (In Search of West Indies

Cricket – Who won the 1975 Shell Shield? -15th May, 2016). Under Findlay’s astute leadership, the

Combined Islands, perennial doormats in the Shield, finally came of age. After the two trial matches

between the Windwards and the Leewards, both won by the former, a confident Skipper Findlay

predicted, “If the Islands don’t win [the Shield] this year, it probably will be a long time before they do.”

“In 1975, Danny Livingstone was the Combined Islands Manager. An Antiguan, who had played for Hampshire [1959 – 1972] in the English County Championships, he moulded us together as a team. We planned every match. Each session was detailed down to runs and wickets. Everyone was fully aware of the plans,” Findlay related.

The Islands led Guyana on first innings in a drawn game in Grenada, and then defeated Barbados by 163 runs at Kensington Oval, their first victory over the Bajans. Next, led by a century from Richards, they surpassed Jamaica’s first innings total of 348, as Findlay, 46 not out, and Hugh Gore, 25, added 62 for the tenth wicket. After overhauling the Jamaican score, the pair were mobbed by an invasion of delirious fans at the Antigua Recreation Ground. In the final round, after conceding first innings points to Trinidad, Findlay’s side needed an outright win to snatch the Shield from Guyana, which having completed its quota of matches, led the points table with 28.

Chasing 283 runs in 263 minutes, it came down to the final delivery, with Gore and Findlay (the last pair again) at the wicket, requiring three runs to win the Shield. In a 2016 telephone interview, Findlay recounted one of the most famous last balls in West Indies cricket history: “Jumadeen was the bowler. Gore drove the ball back past the bowler and we took off. As I turned for the second run, the fielder was about to throw to the bowler’s end. I dived at full stretch. My dive took me past the wicket and the umpire. As I tried to get up, I noticed Umpire Stanton Parris turning down Jumadeen’s appeal for run out. The wicket was broken and the ball was in Jumadeen’s hand. The game was over.”

The controversy over the official result, ‘drawn with scores level’, raged for months, as voices up and down the necklace of the Windward and Leeward Islands screamed for ‘justice’, for the match to be ruled a tie, and the Shell Shield to be awarded to the Combined Islands, which finished the competition, as runners-up with 26 points. Amidst the brouhaha, there were few calming voices from the Islands. Findlay, also known as ‘The Pope’ to his cricketing brethren, for being an absolute stickler for sportsmanship, refused to be lured into the uproar, simply saying that he would abide by the rules. Test colleagues cited Findlay’s diving catch down the legside to dismiss the New Zealand opening batsman Glenn Turner in the 1972 Third Test at Kensington Oval, when he asked Sobers, his captain, to recall Turner after Umpire Kippins had upheld the appeal, since he wasn’t sure if he had taken the catch cleanly.

At the apogee of his captaincy of the Combined Islands, with the ultimate prize so near and yet so far, ‘The Pope’ was the epitome of graciousness, accepting the WICBC’s final ruling that the match was a draw and the Combined Islands were second. The office of captaincy dictates that a moral code of conduct must be adhered to at all times.

“Leadership is not confined, or restricted to the playing field. A good captain, a good leader, has to give and gain respect in every aspect of life,” Findlay, glancing at his notes, explained over breakfast.

“He must understand and think about his players all the time, be aware of their mood changes, and appreciate their disappointments within the game. A captain’s loyalty to his players never ends, and he must ensure a feeling of camaraderie and friendship in the dressing room. Whilst professionalism lends to fierce competition and playing hard, your opponents are not the enemy. Having leadership thrust upon you, one must adopt and develop leadership qualities, and lead by example.”

It’s a captain’s burden to have to weather the vagaries of high expectations and the agony of defeat and poor performances, dimensions to which Findlay can readily relate. In the 1975 Windward Islands tournament, Dominica, with innings victories in all three matches, retained the Heineken Trophy, whilst Findlay’s Vincentians had to settle for the runner-up position, following outright wins over St Lucia and Grenada. In the latter game, Findlay was 99 not out when victory was secured.

In the 1976 Shell Shield the weather wreaked havoc with all the Islands’ matches. The next two seasons were additional servings of bitter disappointment. In the first, the Islanders defeated Jamaica by nine wickets in St Vincent, and fell short of outright wins over Guyana and Trinidad & Tobago after securing comfortable first innings leads. Their final match against Barbados held on the Easter weekend, between the Fourth and Fifth Tests of the Pakistan Tour, was billed as the ‘unofficial Sixth Test’ of the season, as the two teams were tied at the top of the points table. Winning the toss, Findlay invited the home side to bat. They posted 511 runs on the board, as the visitors bowled and fielded poorly. Forced to follow on, despite a century from Richards, the Islands lost by six wickets, as Allen’s second innings hundred saved the embarrassment of an innings defeat. 1978 witnessed Findlay’s team tied for second with Jamaica, as Barbados retained the title. Losing to Guyana by five runs at Bourda in a thrilling match in which the momentum swung back and forth throughout, probably cost Findlay the elusive title in his final year in the Shield. Under his tutelage, the Combined Islands had risen from minnows to full-fledged competitors.

In June 1978, Findlay collected the Heineken Trophy as St Vincent ended Dominica’s four-year reign in the Windward Islands tournament. After missing the 1979 tournament, Findlay returned in 1980 to lead a well balanced Vincentian team to another title, in the absence of Dominica, still suffering from the ravages of Hurricane David in 1979. Findlay marked his comeback with an even hundred versus Grenada at Arnos Vale, St Vincent. Two years later, Findlay called it a day in a match at home to arch rivals Dominica, where Stanley Hinds donned the gloves.

The Combined Islands, under Viv Richards, finally won the Shell Shield in 1981, the last year that the Windwards and Leewards played as one team. Irvine Shillingford, the lone survivor from the inaugural 1966 tournament was a member of the team. In 1982 and 1983, the Windward Islands were the surprise team in the tournament, finishing in the runners-up position on both occasions. Wilf Slack, Findlay’s cousin from Troucama, then playing for Middlesex, was encouraged by Findlay to return for the Caribbean, and his influence was immediate. In the two years, the Windwards achieved the unique feat of inflicting back-to-back losses on Barbados, at Kensington – their first defeat at home since 1975 – and at Arnos Vale. Findlay managed the team in 1983.

West Indies duties

In 1978, Findlay was assigned the responsibility of managing the West Indies Young Cricketers on their tour of England. It was just the beginning of his off-the-field duties for the West Indies, where his experience of two England tours with the Test proved invaluable. In 1997, Findlay was appointed a West Indies selector, remaining on the panel until 2002, while serving as chairman from 1999 to 2002.

In 2007, Findlay was appointed manager for the Tour of England, just after the West Indies hosted the World Cup and Brian Lara’s retirement from Test cricket. Although Findlay was the chairman of the tour party selection committee, he noted that the Test XI will be picked, “…in consultation between the selectors in England and the selectors in the Caribbean… it’s no longer going to be where the [tour] selectors will do their own thing.” Meeting with the press at Grantley Adams International Airport prior to the departure to England, Findlay duly noted that the players had been given a code of conduct and anyone breaking the rules would pay the penalty.

He was also the manager on the subsequent tour, the inaugural ICC World Twenty20 Championship held in South Africa in September 2007, before declining any further managerial positions, citing work and family commitments. Findlay also served as Chairman of the West Indies Cricket Board’s Cricket Committee, the Board’s Representative on the ICC Cricket Committee, and as West Indies Cricket Ambassador. In May 2019, he was one of three Independent Directors of Cricket West Indies appointed to a two-year term in office.

Witnessing a great wicketkeeper like Findlay in action, one’s gaze becomes fixated on the hands; gloved, with ‘inners’ adding another layer of protection; synchronized, outstretched, effortlessly snaring wides, chasing improbable chances, plucking impossible catches. Wicketkeepers are forever on their haunches, disguising their ballerina balance, poised like predators, uncoiling instantly with every delivery for uncharted flight. The padded limbs, apparently instinctively reading the line, glide to the ball’s projected path, attached torso and hands in tow, the latter pair scything the air. The game pauses for a blur, time freezes, a flying edge from the dangling bat, a batsman’s life hangs precariously, hinging upon the deftness of the hands.

Cricket West Indies can honour the legacy of Michael ‘Mike’ Thaddeus Findlay, popularly referred to by his cricketing brethren as ‘The Pope’ by instituting an Annual West Indies Sportsmanship Award in his name. In his own words, “I never felt any inclination to live abroad.” It was his Mike’ destiny to be the keeper of the Islands’ flames.