Richard Drayton, born in Guyana and also a citizen of Barbados, is a Professor of Imperial and Global History at King’s College London

Brinsley Samaroo, who died on 9 July 2023 at the age of 82, was a historian of great originality, and a key figure in the intellectual and political life of Trinidad and Tobago. He spent his whole career at the University of the West Indies campus at St. Augustine in Trinidad, where he rose to Professor of History and for a spell, Director of the Institute of Caribbean Studies, and where he worked constantly, to the end of his life, in its research library.

Brinsley Samaroo, who died on 9 July 2023 at the age of 82, was a historian of great originality, and a key figure in the intellectual and political life of Trinidad and Tobago. He spent his whole career at the University of the West Indies campus at St. Augustine in Trinidad, where he rose to Professor of History and for a spell, Director of the Institute of Caribbean Studies, and where he worked constantly, to the end of his life, in its research library.

During the 1970 Black Power Revolution and in the 1970s turbulence, he was a quiet interlocutor with both urban and rural insurgents, even covertly assisting the National Union of Freedom Fighters.

He was Opposition Leader in the Senate for the United Labour Front from 1981-86, and a Member of Parliament and Minister in the government of the National Alliance for Reconstruction from 1986-1991.

I only met Samaroo in passing a few times. Others who were closer to him, such as Dr. Gabrielle Hosein and his contemporary, the great critic Kenneth Ramchand, have celebrated his warmth, generosity, dry humour, his brilliant teaching, and his fight for the preservation of the architectural and archival heritage of Trinidad, in particular of the sugar industry.

Kirk Meighoo has written of Samaroo’s immense love and care of his severely disabled daughter Naila, for whom he designed his house so she would be able to move freely and enjoy sun and breeze.

My portrait here is drawn through his body of work, which deserves our witness.

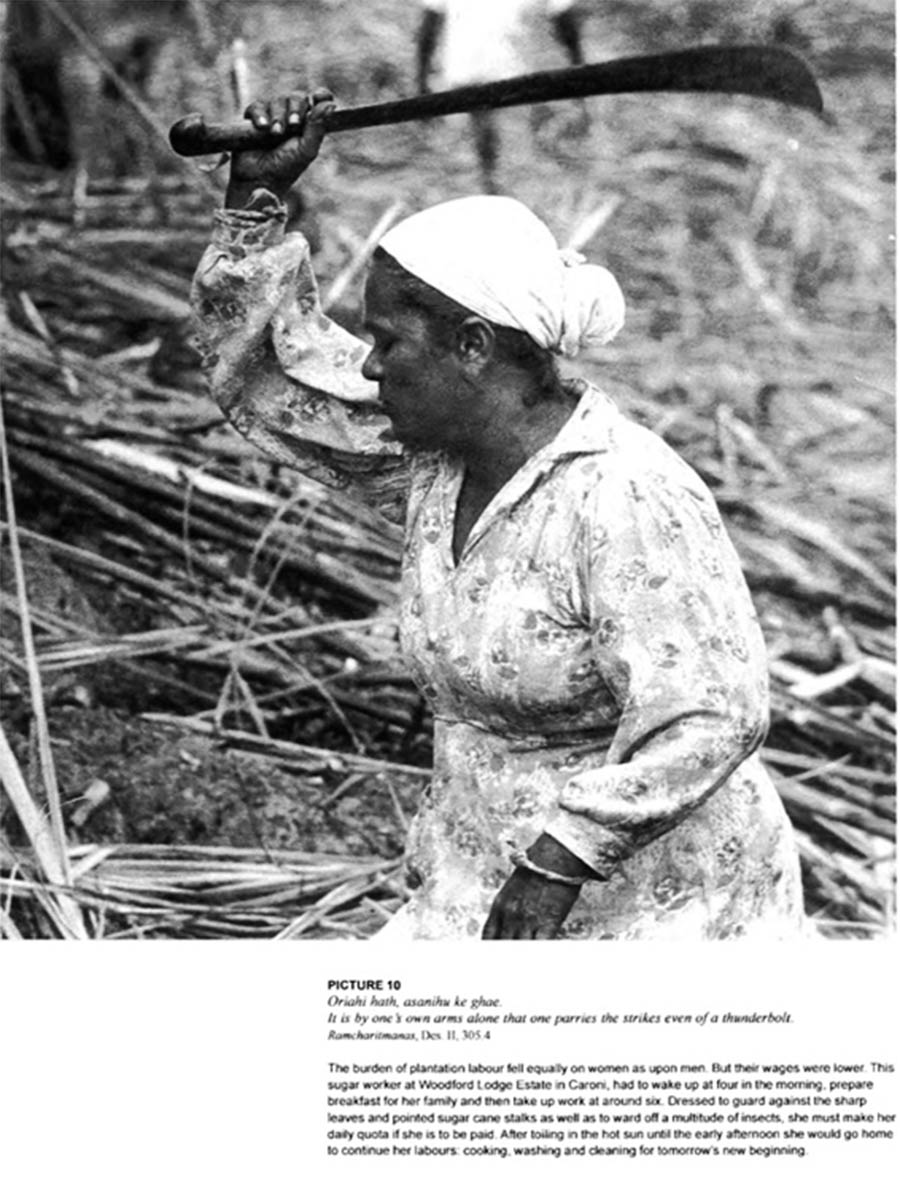

If you want a window into the beautiful generous genius of Brinsley Samaroo, look at Glimpses of the Sugar Industry: the Art of Garnet Ifill* (2003), where Samaroo juxtaposes Ifill’s extraordinary photographs of labour and survival on the plantation to historical commentary and verses from the Urdu poet Mirza Ghalib (1797-1868) and others. Take picture 10, where under a picture of a woman cutting sugarcane with a cutlass, he wrote, “The burden of plantation labour fell equally on women as men. But their wages were lower.”

If you want a window into the beautiful generous genius of Brinsley Samaroo, look at Glimpses of the Sugar Industry: the Art of Garnet Ifill* (2003), where Samaroo juxtaposes Ifill’s extraordinary photographs of labour and survival on the plantation to historical commentary and verses from the Urdu poet Mirza Ghalib (1797-1868) and others. Take picture 10, where under a picture of a woman cutting sugarcane with a cutlass, he wrote, “The burden of plantation labour fell equally on women as men. But their wages were lower.”

This sugar worker at Woodford Lodge Estate in Caroni had to wake up at four in the morning, prepare breakfast for her family, and then turn up for work at about six….,” adding a verse from the Ramcharitmanas, the epic 16th century poem of Tulsidas, which he translates as “It is by one’s own arms alone that one parries the strikes even of a thunderbolt”.

Or we may turn to his 2021 biography of Adrian Cola di Rienzi (born Krishna Deonarine), whom Samaroo called the East Indian-West Indian, who after a circuit overseas during which he participated in Irish republican, Indian nationalist, Garvey’s UNIA Pan-African and Comintern politics, returned to Trinidad where he founded both the Oilfield Workers Trade Union (in collaboration with “Buzz” Butler) and the All Trinidad Sugar workers union. This was, Samaroo explained, “the first time in the history of Trinidad &Tobago that the two major races came together,” forming a class unity across race.

Samaroo dedicated his gifts at once to illuminating his ancestral community’s experience, and to working towards a national cross-race emancipatory future for Trinidad. It was towards that larger end that he sought to rescue the history of working-class struggle and demands for democratic government from the 1880s to, and after, political independence.

He may be compared to Walter Rodney, born two years later, for whom a concern for the special experience of the African diaspora was entangled with larger projects for Guyanese, Caribbean and global futures. That he was proudly “Indian” was never in contradiction with his pride and commitment to Trinidad and to the common past and future of the descendants of enslaved Africans and indentured Indians.

Two emblematic contributions here were his research on Islam as a common ground of African and East Indians in early 19th Century Trinidad; and his discovery of a ship which partially filled with East Indians, then stopped in West Africa to pick up indentured labour there, before coming to Trinidad.

Samaroo saw Trinidad, literally and metaphorically, from below. He was a product of a minority, a community strung between Hinduism and conversion by the Canadian Presbyterians, whose influence was particularly strong on Naparima College, the superb secondary school which produced him like so many other prominent Indo-Trinidadians.

But it is key too that he was a product of San Fernando, the southern second city of Trinidad, both close to, and far from, the power and status of Port of Spain. San Fernando, ten kilometres west of the climax of the sugar industry at the Usine Ste Madeline, the key to “East Indian” experience, and twenty kilometres north of the oilfields, where Black labour dominated, was both far more influenced by trade union struggle, and perhaps the first and most important site for African and Indian cultural and political exchange.

Samaroo took the radical decision to go to university not in Jamaica or England, but in India, where he completed his BA and MA at Hindu College of the University of Delhi. He then went to the University of London, where in 1969 he completed his PhD thesis on “The Constitutional Development of Trinidad, 1898-1925”.

He argues there that working class politics and democratic assertion at the turn of the century underpinned the better-known mobilization of the 1920s and 30s. He illuminated, for example, the rise in 1897 of the Trinidad Workingmen’s Association, the first workers’ organisation in the British West Indies, from the coalition of fifty carpenters, masons, tailors, labourers, and traced the rise of revolutionary politics after 1917, culminating in violent state repression in 1920 with mass arrests, detention, shooting and a Sedition Law.

This was never, alas, published as a monograph, but parts of it appeared in key articles on the Trinidad Workingmen’s Association, and on the 1917-20 disturbances as a precursor to 1937.

What he is best known for internationally was his pioneering role in creating the field of Indo-Caribbean history.

In the 1970s he turned to the problem, beginning with his collaboration on East Indians and the Present Crisis (1978), but with a climax in his work with David Dabydeen on Indian in the Caribbean (1987) and Across Dark Waters (1996), the 1995 celebration of 150 years of Indian contributions to Trinidad and Tobago, and (with Anne-Marie Bissessar) The Construction of an Indo-Caribbean Diaspora (2004).

He was negotiating what is now called “Coolie-tude” before it was cool: with friends and collaborators in Fiji, Mauritius, Natal and India, he brought together a global conversation on the common experience of the Indian indentured labourers and their descendants. In one of his last articles, he examined the environmental history of the “orientalisation” of the Caribbean, the impact of the migration of plants and animals- such as the oxen of the Gangetic plain – from India to the region.

The Blackest thing in Slavery was not the Black Man: The Last Testament of Eric Williams (2022) was Samaroo’s last gift. It resulted from the challenge, entrusted to him by Erica Williams Connell, of editing a vast manuscript which Eric Williams had worked on, in a somewhat chaotic way, in the decade between the Black Power revolt and his death in 1981. For Brinsley this was a poignant task, since of course, its composition was contemporary with that decade in which he was in political opposition to Williams.

His editing is sympathetic and respectful of William’s predicament and achievement, reminding one of how Lloyd Best, in later life, wrote to Arthur Lewis with some regret at the terms with which he had confronted him as a young man. It reveals a Williams, riven by contradictions, on the one hand praising W.E.B. DuBois and Walter Rodney, and even celebrating the Ras Tafari movement as “the first effective Caribbean repudiation of Europe—after Haiti”, while on the other writing coolly about the crushing of the Black Power Revolt.

Samaroo admired in Williams his ambitions for Caribbean civilisation. In an interview, filmed in 1987, when he began his brief career as a Minister, Samaroo shared his vision of how mass media might make the people conscious of their own history, and of the distinct and common experiences of all the constituents of the society.

He saw his own prodigious labours as a researcher and writer as a contribution to that work. He lived and died by one of his favourite quotations from RabindranathTagore: “We have no time to lose, and having no time we must scramble for our chances, we are too poor to be late”.