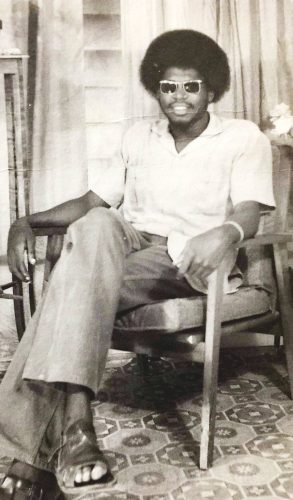

Having worked here in 1974 as a secondary school teacher fresh out of the University of the West Indies, Barbadian financial management and financial analysis consultant William Layne developed a love for Guyana. He has visited the country regularly and has maintained contact through friendships built since then and throughout his professional life.

“I love Guyana. I feel safe and comfortable. Most of my friends are Guyanese who have lived outside of Guyana. We’re like family. … Guyanese are extremely welcoming and hospitable people unlike any other people I’ve met elsewhere. A number of my Caribbean colleagues who lived in Guyana, or worked at Caricom, or visited Guyana on business have said the same thing to me when I tell them of my experiences. Guyana is like home to me, like Barbados is home,” Layne told Stabroek Weekend from his home in Barbados.

In 2011, when a senior Barbadian government official asked him if he would be willing to serve on the Caricom Audit Committee, and that it would entail travelling to Guyana for at least two meetings a year, Layne accepted.

Layne, now 73, is the incumbent chairman of the audit committee, established in 2011 by Caricom Heads of Government to look at the operations of the secretariat and its organs to ensure they operate within the rules and regulations that established them.

He served for four years on the first committee. He was off for the following four years then returned for the period 2019 to 2023. Born in Worthing View, Barbados, he attended the then Boys Foundation School in Christ Church and did his sixth form schooling at Barbados Community College. He obtained a bachelor’s degree in economics, and sociology and history from the University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus in 1973.

He taught for six months at Ellerslie Secondary School in Barbados before teaching in Guyana.

Hooked on Guyana

Layne’s fascination with Guyana started with a Guyanese friend whose father taught at the Cave Hill Campus. “He told me all these stories about growing up in Guyana that got me excited,” he recalled.

In 1974, Layne and another UWI graduate teacher visited Guyana during the Easter holidays. “We were both taken in with developments in Guyana under Forbes Burnham,” he said. “In my case, I was also caught up in the novels of Edgar Mittelholzer and the works of Wilson Harris and Jan Carew. Guyana was frontier-like in my view.” When Layne and his friend arrived at the then Timehri International Airport, they did not know where they were going to stay. “The immigration officer told us to put ‘guest house’ on the form, so we did.” After clearing immigration, they asked a taxi driver to recommend a place where they could stay.

“He took us to Le Grille Guest House on Middle Street. It was run by a Guyanese woman with an Italian husband, a Mr Mancini. The next day Mr Mancini walked us around the city and took us to the bank to change our money. He warned us to stay away from Tiger Bay,” Layne said. They had the addresses of two Guyanese given to them by another UWI graduate who had worked in Guyana for two years. “We called on them on the second day. They welcomed us into their homes with real fanfare,” he recalled. “They became our friends for life. They seemed to know everyone in Georgetown. We went with them to a number of parties and we enjoyed ourselves.”

The following week, the two met with then deputy chief education officer Benjamin Agard, whose father was Barbadian and who told them the Ministry of Education would be glad to have them as graduate teachers in one of the secondary schools. Layne went back to Barbados and resigned at the end of the school term to return to Guyana.

“I was 23 years old,” he recalled. “I told the headmaster at Ellerslie I liked what was happening in Guyana with its government’s plan to feed, clothe and house its nation. I wanted to be part of it. My friend had second thoughts and backed out.”

Back in Guyana in August 1974, Layne boarded and lodged with a newly-found friend’s godmother, a retired teacher, at 33 Alexander Street, Kitty, which was within walking distance to North Georgetown Secondary School, where he was assigned. “She took me in and looked after me like a son,” he said.

With a letter from the education ministry, he reported on the first day of the new school year to the principal, the late Dr Daphne Persico, and was assigned a fifth form as form master.

“Coming from a country that comprised a 95 percent Black population and a small White population with English traditions, where all the names were basically English, my first exposure to Guyana as a multicultural and multiracial society was very interesting,” he recalled. “I had a difficulty pronouncing some of the East Indian names.”

Layne immersed himself into the multiethnic and multiracial society and experienced a bout of diarrhoea. “I delved into the food, which was a rich cultural experience. My landlady warned me that my diet was going to be different and to expect a lot of spicy foods. I remember she bought me some Ferrol Compound to drink every morning for about a week to build my strength back.”

His breakfast included roti and curry one morning, pepperpot and cassava bread, or, bake and saltfish on other mornings, compared to having bread and egg and bread and cheese for breakfast in Barbados most mornings. He also made use of the variety of fruits available.

“Coming from a little island, 21 by 14 square miles, the sheer size of Guyana was an amazing experience. The first time a friend took me on the ferry to West Bank Demerara, I said to her, ‘The sea in Guyana is very calm. She laughed and said this is the Demerara River,” he reminisced.

Travelling along the Essequibo River and touring Mackenzie and its bauxite operations, he said, were also memorable experiences.

Entertainment included Sunday after-lunch limes. “I had a friend who always knew where an after-lunch lime was being held. I attended quite a few. That was part of my cultural milieu,” he said

He found it interesting that Georgetown was laid out in blocks by the Dutch, like New York. “So it is easy to find places in Georgetown by lots unlike the eastern Caribbean. In Barbados, the paved streets follow footpaths that meander, so you go around in circles at times and the house lots do not follow any logical lot numbers. You can have Lot 1 here and Lot 29 next door,” he explained.

Another marvel was the massive seawall that keeps Georgetown from flooding because the city is below sea level, “just like Amsterdam in Holland.

“Georgetown, the Garden City, in those days, was beautiful and enchanting. The canals were well maintained.”

Underlying tensions

While Georgetown was an enjoyable experience, as an outsider, he noted underlying ethnic tensions shared with him through his students.

One Indian student told him relations between the two major ethnic groups were not harmonious because of cultural differences. “The differences did not make it easy to make friends with people of the other race, he said. Within their families, they were not encouraged to integrate but to stick with their own kind. She didn’t like that,” he related.

Another of his Indian students invited him to her home for her birthday. When he told one of his colleagues, who was Black, she was surprised. “She said being invited to the home of an Indian family of a student and of a girl, in particular, was not normally done,” he said.

Layne realised that as a foreigner, he could move between the two ethnic groups with some degree of ease.

“One of the Indian parents told me: ‘You are different from these Black people in Guyana’. He didn’t think that was a racist statement. He didn’t see I was only different culturally because of my experiences,” Layne said.

Having lived and worked in Guyana, Layne said he did not think the politicians created its racial divisions. “They used what was happening to their advantage. Politicians in any system are not usually proactive. They usually follow what society wants,” he expanded.

For example, he said, in Barbados during the 2008 general elections when a significant Guyanese population lived there, some members of a political party blamed the Guyanese for some of the economic problems the country was going through.

“So there was this anti-Guyanese sentiment. The then prime minister got on the air and said Barbadians were too xenophobic and we needed to be more open to fellow Caricom people. He had used some Guyanese labour on his projects and he was pilloried for saying that,” Layne recalled. “There was also jealousy over the Guyanese women. A Guyanese calypsonian in Barbados wrote a calypso that said Guyanese women were taking away the Bajan men because Bajan women were giving their men corn curls to eat while Guyanese women were giving them roti and curry, pepperpot and chow mein. While some Barbadian politicians openly embraced what was happening others did not.”

At the time he also found the Indigenous population in Guyana was not well considered in the society. There were preconceptions about the indigenous people and jokes were being made about them.

Noting that plural societies have issues managing cultural differences and gaining consensus, he said, arriving at a consensus was one of the biggest problems facing Guyana. Decisions were considered biased if made by the other group.

The system of proportional representation, he feels, is a good one because it ensures there is always an opposition in place as part of good governance, and “not like Barbados where we have a first-past-the-post system and no opposition. Politically, Guyana is not an easy country to manage. It’s future I think lies in some kind of coalition establishment.”

He noted that the banks and certain businesses in those days employed people based on their race and the level of the colour of their skin. “These things struck me as divisive. Some of them have since changed,” he added.

The issue of racial and ethnic differences is part of the Caribbean’s colonial heritage to maintain control, he said.

Outside of the political arena. Layne found a willingness to be socially integrated and some amount of social integration. “Some of my friends, like those who lived in New Market Street and who now live in New York, came from all the races in Guyana and they get along very well,” he noted.

Jamaica

At the end of the school year in 1975, Layne returned to Barbados, worked at the Ministry of Trade as an economist for a year, then went to Jamaica in 1976 where he taught at Morant Bay Secondary School in St Thomas parish for two years.

“Before going to Jamaica, I went down to Guyana to see my friends, then back to Barbados and off to Jamaica,” he said.

He found Jamaica, like Barbados, to be very class conscious with a small upper class that controlled the business sector and a significant middle class. “A number of problems arose from the class structure which led to some political violence around election time,” he noted.

In Jamaica’s 1976 general elections, Layne, 26 at the time, felt invincible and supported the People’s National Party led by Michael Manley.

“At the time UWI graduates in social sciences were all left of centre and supported the socialist parties. Michael Manley, like Forbes Burnham, was a fantastic orator. [I was] fascinated with Burnham, he was one of the reasons I had gone to Guyana, and Manley was another reason I had gone to Jamaica. Manley had introduced democratic socialism in Jamaica and Burnham, cooperative socialism in Guyana. They both had the vision to uplift the poor,” Layne said.

However, Jamaica was “an awakening” for Layne. “I realised as a young person that idealism must be tempered with reality. Instead of creating heaven for the people, you created hell for them,” he added.

He noted the United States did not take kindly to little Jamaica pursuing a non-aligned role, establishing close relations with Cuba and actually voting against the US at the United Nations. “Economic pressure was put on Jamaica, the economy started to disintegrate as happened in Guyana,” he noted.

There were shortages of food and foreign exchange in Guyana and Jamaica.

“By the time I had left Jamaica, it had experienced its first devaluation and Guyana had also been through it. It was wreaking hardships on the poor people,” he recalled.

Layne moved back to Barbados in 1978 and left secondary school teaching. He continued travelling to Guyana as often as he could on long weekends to hang out with his friends.

“When I returned to Barbados in 1978 from Jamaica, my parents’ house became a transit stop for a number of my Guyanese friends on their way out of Guyana. Many had begun to migrate from about 1976. They stopped over sometimes for a week or two. Some went to Canada before making their way to the US,” he related.

After his return to Barbados he worked for five years in the public service, first as an economist and then as a research officer in aviation and tourism.

He then went on to study accountancy in Canada. From Canada he went to New York to meet his Guyanese friends.

“One time I went to a barbecue and it was the whole of New Market Street there. Some were living in Queens and some in Brooklyn. I said to them, ‘When I met you guys in Guyana in 1974, I expected we would always keep in touch, that you would come up to Barbados to see me and I would go down to Guyana to see you. I never envisaged we would be meeting up so far away from our home countries and more so in the cold.’ At the time we never imagined living away from the Caribbean except to study,” he said.

Layne also keeps in contact with friends who remained in Guyana like Donald Sinclair and Cecilia McAlmont, his former colleagues at NGSS.

“I also keep in touch, through technology, with some of my Guyanese and Jamaican students who are all over the world,” he stated.

The export of the region’s better brains, he said, is one of the tragedies of life he found as a Caribbean man who dreamt of growing up and building a sustaining place where all people would earn a decent living. While migration is the story of human civilization, he noted, “The large-scale migration from Guyana and Jamaica because of economic failures is a cause for concern.”

Nevertheless, he said, “I would recommend young people spending some time away from their land of birth. It makes you more culturally aware of the world and the differences you have to learn to appreciate for a meaningful life.”

Layne spent three and a half years in Canada where he got married and had a son. On his return to Barbados his work kept him in touch with Guyana.

He first rejoined the public sector as a management accountant in the Ministry of Finance, then moved to the then National Insurance Department as the finance controller. He was subsequently appointed the supervisor to regulate the insurance industry, after which he was appointed the director of social security. In these positions he attended regional social security meetings some of which were held in Guyana.

His last public service appointment was permanent secretary in the Ministry of Finance, a position he held for ten years before opting for early retirement in 2010. As permanent secretary he attended Caricom meetings in Guyana.

After a six-month break, he took on a consultancy for a hotel and became a director, then he did a number of projects for the government under the area of financial management and analysis, which he still does.

He is also on a number of boards of directors for private and state entities including Republic Bank (Barbados) and the Life of Barbados which was started by Guyanese Cecil de Caires, who moved his company from Guyana to Barbados in the 1960s.