Denis Williams’s (1923 – 1998) December 1950 exhibition shortly after his return to London at the Gimpel Fils Gallery was a success. The exhibition earned him recognition and patronage in the London art world and forced British Guianese to look at his work without the biases of their allegiance to traditional forms and themes in art. And while the painting Human World (1950, see Eye on Art July 16) was acquired for the British Guiana National Art Collection arriving in 1956, the work that was being considered for Tate Britain (see Eye on Art July 9) was not.

Denis Williams’s (1923 – 1998) December 1950 exhibition shortly after his return to London at the Gimpel Fils Gallery was a success. The exhibition earned him recognition and patronage in the London art world and forced British Guianese to look at his work without the biases of their allegiance to traditional forms and themes in art. And while the painting Human World (1950, see Eye on Art July 16) was acquired for the British Guiana National Art Collection arriving in 1956, the work that was being considered for Tate Britain (see Eye on Art July 9) was not.

Once again resident in London, Williams continued to show at the London and Paris Gimpel Fils galleries and in significant exhibitions around London including ‘Eleven British Painters: Recent Work’ at the Institute of Contemporary Art in 1953 and the watershed ‘This is Tomorrow’ at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1956. According to the Whitechapel’s online archive, the exhibition responded to the new technologies of the 1950s and tasked the 38 participants, formed into 12 groups “[composed of] an architect, a designer, an artist and a theorist, [to] amalgamate their individual approaches and produce a work by deploying a new methodology.”

For this exhibition, Williams worked alongside US-born artist John Ernest (1922 – 1994) and British artist Anthony Hill (b. 1930). The exhibition was innovative in its conception and realisation and has remained a subject of study for artists and curators. In 2010, the Whitechapel hosted an exhibition on the making of ‘This is Tomorrow’, which included documents from the production process and the final results of the collaborations such as the original promotional posters designed by each group, artists’ personal correspondences, and rarely seen photographs.

Williams, therefore, was a regular presence on the London art scene in the 1950s. However, his exhibited works were a visual departure from his earlier figurative paintings of Guiana and early London days. They evidenced a profound engagement with the ideas dominating a shift to abstraction and non-representational painting that characterised post-War British art. Painting in Six Related Rhythms (1955), now in the Tate Britain collection since 2020, is from this period.

Also during these London years, Williams taught at the Central School of Art (which later merged with the Saint Martin School of Art to form the Central Saint Martin School of Art) and was a visiting tutor at the Slade School of Art, University College London. His presence at both institutions allowed him to be engaged with the current discourses on art.

In 1957, Williams moved from London to Khartoum, the capital city of the newly independent Republic of Sudan. Here he was attached to the design school, a carry-over from colonialism, which by that time was subsumed within the Technical Institute of Khartoum. (Today, it is the College of Fine and Applied Art of the Sudan University of Science and Technology which after years of funding neglect continues to struggle to serve and be relevant to its students.)

Then in 1962, he moved to Nigeria where he remained until 1967. Early in his residency there, he directed two art workshops, one of which he did alongside US-born Jacob Lawrence (1917 – 2000).

While resident in Nigeria, Williams also taught at the School of African Studies, University of Ife and later at the School of African and Asian Studies, University of Lagos. His time in West Africa appeared to have been very productive and culminated in his book “Icon and Image: a Study of Sacred and Secular Forms of African Classical Art” (1974).

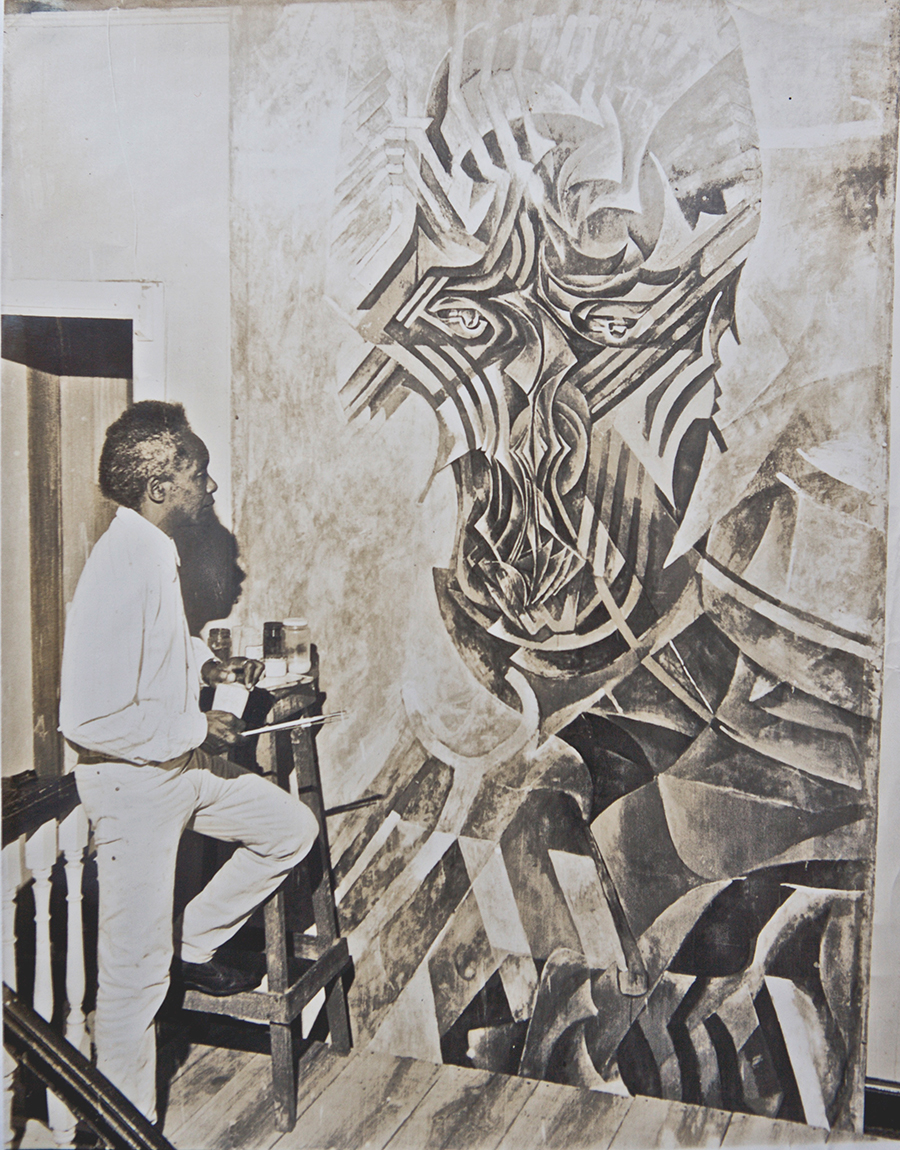

Williams returned to Guyana in 1967. By this time, he had gained substantial exposure to archaeological practices, starting out in Sudan. He first lived at Issano in the Upper Mazaruni where he conducted extensive archaeological research. His collection of artefacts found in the Mazaruni environs were later donated to what would come to be called the Walter Roth Museum. In Georgetown, in January 1969 he delivered the inaugural Edgar Mittelholzer lectures collectively titled ‘Image and Idea in the Arts of Guyana’. He was also appointed director of the National History and Arts Council in 1969. In 1974, he was appointed director of Art and completed the large painting Majestas which was initially taken to the Anglican Church in Kamarang. In 1975, he established the E R Burrowes School of Art, of which he was the first principal until 1982. He relocated to the Walter Roth Museum to serve as its director until his passing in 1998. Williams was also instrumental in establishing the Museum of African Heritage in 1985.

Williams wrote copiously on African art, drawing on the material encountered during his time living on and travelling across the continent. He founded Archaeology and Anthropology, Journal of the Walter Roth Museum and sustained it by contributing substantially in multiple ways. He coordinated the national art collection, pressed for a national gallery, and was meaningfully involved in art exhibitions for Guyanese artists in Guyana and the region, writing numerous catalogue essays in the process. Williams was also responsible for a programme of public art and monuments to which he also contributed with the mural Memorabilia II (1976) which is in the National Cultural Centre and the Enmore Martyrs Monument (1977) sited in Enmore Village.

Williams was awarded an honorary doctorate for his work in archaeology by the University of the West Indies, as well as the Cacique Crown of Honour from the Government of Guyana in 1989. He had previously been awarded an Arrow of Achievement in 1973. Williams died at his home in D’Urban Backlands on 28 June, 1998. He was buried in St Sidwell’s Churchyard, on 4 July.

After collating notes from Eve Williams’s ‘The Art of Denis Williams’ and the writing of other scholars, I know I have only scratched the surface on Denis Williams, the artist; this was the focus of the essays these past weeks. I reiterate here that the intention was to introduce this great man of our soil to students of art – young and old – as one to emulate. To highlight an important takeaway, Williams was well-read on his discipline and pushed his own boundaries when he could have settled into zones of comfort with his successes. He was also a man who thought about the business of art in terms of its functions to society and tried to actualise these.

Akima McPherson is a multimedia artist, art historian, and educator