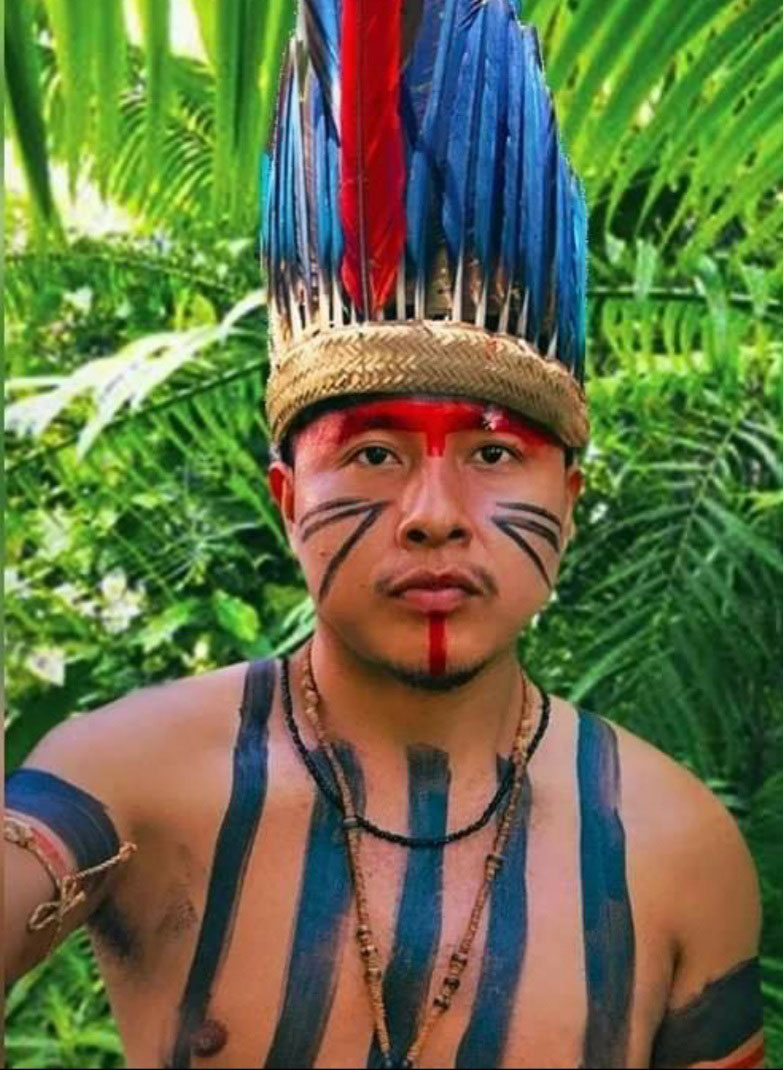

A master’s degree student in water governance and water management, Romario Hastings is eager to banish the stereotypes and preconceptions surrounding Indigenous People and intentionally adopted the Akawaio name, ‘Kapohn’, once he became culturally aware of his identity.

The 29-year-old who is also a digital creator and youth advocate, and uses the name for his social media handles, said: “I believe we are more than just a display of culture. There are so many things to learn from us, if we seek out these things with a researcher’s mindset and develop a deeper meaning to some of what may be considered simple. During my undergraduate studies, I did some courses in social movements and advocacy. I did an internship with the Amerindian Peoples Association on youth advocacy and policy because as Indigenous Peoples we are desperate for advocacy as much as we pursue our careers in engineering, medicine, in the political field or whatever area it is.”

Hastings, who was in Aishalton wrapping up his fieldwork for his master’s degree thesis on water management, when Stabroek Weekend caught up with him, said, “I have been fortunate to experience life in the hinterland, in the city and now internationally as a student at the IHE Delft Institute for Water Education. I have narrowed my focus to water governance and water management and policy-related matters with my profile on ecosystems health and water resources.” He would like to obtain a doctorate eventually.

Hastings, a former hinterland scholarship student, began his educational journey at Kako Primary in Region Seven, Cuyuni/Mazaruni where he wrote the then Secondary School Entrance Examinations and secured a place at President’s College (PC).

“President’s College was the first time I was out of my comfort zone,” he recalled. “I experienced a number of culture shocks, the language, the food and even relating to students from other ethnicities. Some hinterland students returned to the secondary schools in their home areas like at St Ignatius Secondary in Lethem. I had no option. I was a quiet and shy student.” Hastings said it was uncomfortable for him to start conversations with his coastal colleagues because they all spoke in Creolese which was new to him. “I felt very out of place speaking standard English. I had to deal with all the preconceptions of who and what Indigenous people were or are. There were lots of questions,” he said. “As a preteen, I was still forming my identity and trying to understand who I was. There was no form of support system for students like me facing culture shock or other challenging issues coming from an entirely different culture which I think should be present in these boarding schools.”

At that time communication with Kako was very difficult. “We didn’t have digital technology so most of the communication was by satellite. There was no way I could have said, ‘Mom I had a bad day. Could I come home at weekend? I’m missing your food’. It took a while for me to adjust but then in about third form I became more comfortable and confident and I finished school,” he said.

These early experiences at President’s College helped him to be more versatile at adapting to different environments. After PC he took a year off and returned to Kako. He had wanted to do medicine because he was in the science stream at school.