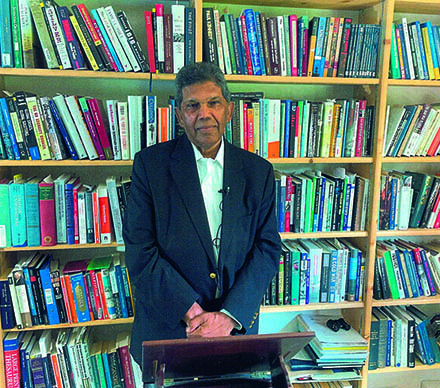

By Dr Bertrand Ramcharan

Chief Speech-Writer to the UN Secretary-General (1988-1992);

Seventh Chancellor of the University of Guyana

In January 1992, the UN Security Council convened at the level of Heads of State and requested the then UN Secretary-General, Boutros Boutros-Ghali to submit to it an agenda for peace highlighting the prevention of conflicts. Later that year, Secretary-General Boutros-Ghali submitted his historic Agenda for Peace, focussing on preventive diplomacy for peace, peace-making, peacekeeping, peacebuilding, and peace enforcement.

I wrote the first draft of this document but I have never been in favour of the inclusion of peace enforcement. I have always believed that the UN should only rarely be in the business of fighting wars. The 1992 Agenda for Peace was a crisp, action-oriented document, and it has served the UN until now – and continues to do so. It led to significant enhancement of UN preventive diplomacy and to the establishment of UN centres for preventive diplomacy in North-West Africa, Central Africa, and Central Asia.

Three decades later, in July, 2023, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres published a policy brief, A New Agenda for Peace. Unlike the 1992 Agenda for Peace, which was formally submitted to the Security Council and the General Assembly for their consideration, Secretary-General Guterrez has published the New Agenda for Peace as a ‘Policy Brief’ for general discussion in the hope that it might influence delegations at the Summit of the Future scheduled for 2024. It remains to be seen whether Governments will be able to take decisions on the broad ideas and proposals put forward by the Secretary-General.

The New Agenda for Peace is a discursive document and one has to dig into it to find actionable proposals. It assesses that a quarter of humanity lives in conflict-affected areas and that conflict is a key driver for the more than 108 million people forcibly displaced worldwide. It estimates that only 12 percent of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are on track. It cautions that the magnitude of the artificial intelligence revolution is now apparent. And it laments that human rights are facing a pushback in all regions: “We see a significant global retrenchment of human rights.”

The New Agenda for Peace puts forward the following three principles for an effective collective security system: trust; solidarity; and universality, namely the universality of norms. Guterres’ vision for ‘multilateralism in a world in transition’ embraces the following: the UN Charter and international law; Diplomacy for peace; Prevention as a political priority; Mechanisms to manage disputes and improve trust; Robust regional frameworks and organizations; National action at the centre; People-centred approaches; Eradication of violence in all its forms; Prioritizing comprehensive approaches over securitized responses; Dismantling patriarchal power structures; Ensuring that young people have a say in their future; Financing for peace; Strengthening the toolbox for networked multilateralism; and An effective and impartial UN Secretariat.

In furtherance of this Sermon on the Mount, he advances twelve recommendations: 1. Eliminate nuclear weapons. 2. Boost preventive diplomacy in an era of divisions. 3. Shift the prevention and sustaining peace paradigms within countries. 4. Accelerate implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development to address the underlying drivers of violence and insecurity. 5. Transform gendered power dynamics in peace and security. 6. Address the interlinkages between climate, peace and security. 7. Reduce the human cost of weapons. 8. Strengthen peace operations and partnerships. 9. Address peace enforcement. 10. Support African Union and sub-regional peace support operations. 11. Prevent the weaponization of emerging domains and promote responsible innovation. 12. Build a stronger collective security machinery.

Guterres has a detailed discussion of these twelve Beatitudes. In what follows, we shall deal with some items that would seem of particular relevance to countries with nation-building challenges or those serving as members of the UN Security Council.

Guterres strongly recommends national action for the prevention of conflicts. He calls upon Governments to develop national prevention strategies to address the different drivers and enablers of violence and conflict in all societies and to strengthen their national infrastructure for peace. He emphasizes that respect for human rights must be at the heart of national prevention strategies. He also highlights the importance of the rule of law.

On the future functioning of the UN Security Council, Guterres calls for the Council systematically to address the peace and security implications of climate change in the mandates of peace operations and other country or regional situations on its agenda. He emphasises that in a number of current conflict situations, the gap between United Nations peace-keeping mandates and what such missions can actually deliver in practice has become apparent. He writes: “The challenges posed by long-standing and unresolved conflicts, without a peace to keep, driven by complex domestic, geopolitical and transnational factors, serve as a stark illustration of the limitations of ambitious mandates without adequate political support. To keep peacekeeping fit for purpose, a serious and broad-based reflection on its future is required with a view to moving towards nimble adaptable models with appropriate, forward-looking transition and exit strategies.”

On the issue of artificial intelligence (AI), Guterres writes that it is both an enabling and a disruptive technology. He recommends the following actions: first, urgently develop national strategies on responsible design, development and use of artificial intelligence, consistent with Governments’ obligations under international human rights and humanitarian law.

Second, develop norms, rules and principles around the design, development and use of military applications of artificial intelligence through a multilateral process, while also ensuring engagement with stakeholders from industry, academia, civil society and other sectors.

Third, agree on a global framework regulating and strengthening oversight mechanisms for the use of data-driven technology, including artificial intelligence, for counter-terrorism purposes.

Returning to the peace and security role of the UN, Guterres recommends: “For the Security Council, ensure that the primacy of politics remains a central tenet of peace operations” (p.24). One cannot help wondering where this leaves the role of human rights and the rule of law – elsewhere highlighted in the New Agenda for Peace.

As a concluding reflection one might ask the question: Is this a document with actionable proposals or a document blowing in the wind?