Rice feeds more than half the world – but we are about to enter a major shortage of this staple, putting food security and livelihoods at risk as prices rise. Yields are falling and crops failing as a result of floods, droughts and severe weather caused by the climate crisis. Rice is also a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, so more sustainable production and cultivation methods are a priority. Each day, more than half of the world sits down to a meal of rice. As a staple food for so many, the amount of rice we produce and consume each year is mind-boggling. Globally, over 165 million hectares – or an area the size of Iran – is given over to rice cultivation. But we are about to enter a major rice shortage, and we’re already seeing prices significantly up in anticipation of demand.

With so many people dependent on the grain, this creates serious food security issues for some of the world’s poorest households. Demand for rice has been steadily climbing as populations expand – between now and 2031, demand is expected to grow 1.1% a year. China and India are the world’s primary producers, although many other countries also grow and export it. It takes 3,000 to 5,000 litres of water to produce 1kg of rice. This makes it particularly prone to increasing and more severe droughts that are occurring because of the climate crisis. Rising temperatures, floods, as well as severe, unpredictable weather as a result of climate change, are also causing harvests to fail.

This is particularly problematic for the 150 million small-scale rice farmers who rely on the income from their smallholdings to live and eat. It is estimated that climate change may lower rice yields by 15% by 2050.

The International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) is working on breeding alternative rice varieties with improved nutritional values, including a low glycaemic index, and providing more dietary fibre. As well as supporting farmers to produce better yields and develop locally-adapted climate-resistant farming strategies, the IRRI is developing new models to involve women and young people in rice production to help. That’s only one side of the story. As much as rice cultivation is a victim of the climate crisis, it is also contributing to it. It makes up 12% of methane emissions and 1.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions. This is largely because the stubble and straw left behind after the rice has been harvested is often burnt, or the fields flooded to encourage rapid decomposition, both of which result in significant gas emissions. Rice cultivation also consumes 40% of global irrigation, accounts for 13% of fertilizer use, and covers 15% of the earth’s natural wetlands. Heavy fertilizer use and gases emitted as part of the harvesting process make rice a significant source of greenhouse gases.

The Global Methane Pledge is a commitment by countries to reduce their emissions of the gas by at least 30% from 2020 levels by 2030. Several countries are targeting rice as part of this pledge. Vietnam, for example, which has long operated a ‘rice first’ policy, is now looking to shift away from intensive rice farming as it joins the drive to reduce emissions. Through improved irrigation, tillage practices and seeds, as well as tailored fertilizer application and farmer training, it is managing to increase yields and ‘green’ its rice production. This includes changing the cropping pattern, to rotate different crops, and changing the cropping time to avoid saline water intrusion, which affects some varieties. There are also improvements to be made during the growing and harvesting processes. These include breeding and engineering higher yielding or more drought-, flooding-, saline- and pest- tolerant varieties. Alongside this, efforts are being made to cut pesticide and nitrogen-based fertilizer use, instead using bio-fertilizers. Growing techniques such as alternative wetting and drying are also being experimented with as a way to curb water use and emissions.

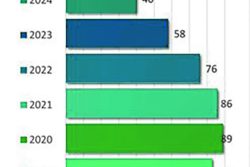

Some countries are looking to shift away from intensive rice farming in order to reduce emissions. Image: Statista

Some of the biggest rice producers globally have been experimenting with alternative ways of dealing with rice straw and stubble.

The Happy Seeder Machine puts mulched stubble back into the field, and has been shown to cut emissions by three-quarters, as well as boost yields. Rolling out machinery like this on the scale required would be a significant investment. Rice straw also has a number of potential uses, such as for soil improvement, cattle feed and for use in paper or making fibre board. While some options are being investigated, others are not economically viable.

Supporting small-scale production

The large number of small-scale farms is also a significant hindering factor to offering solutions. These farms tend to be characterized by low productivity and high-risk value chains, with limited access to market and lowland security. This makes financial investment unattractive given the low margins, high complexity and considerable risk on returns.

Editor’s Note: This article was published by the World Economic Forum on June 6th, 2023. It has been edited for length while its instructive insights have been retained for their relevance to local readers.