In this week’s edition of In Search of West Indies Cricket, Roger Seymour looks at the Lord’s Test Match of the 1984 West Indies Tour of England.

Prologue

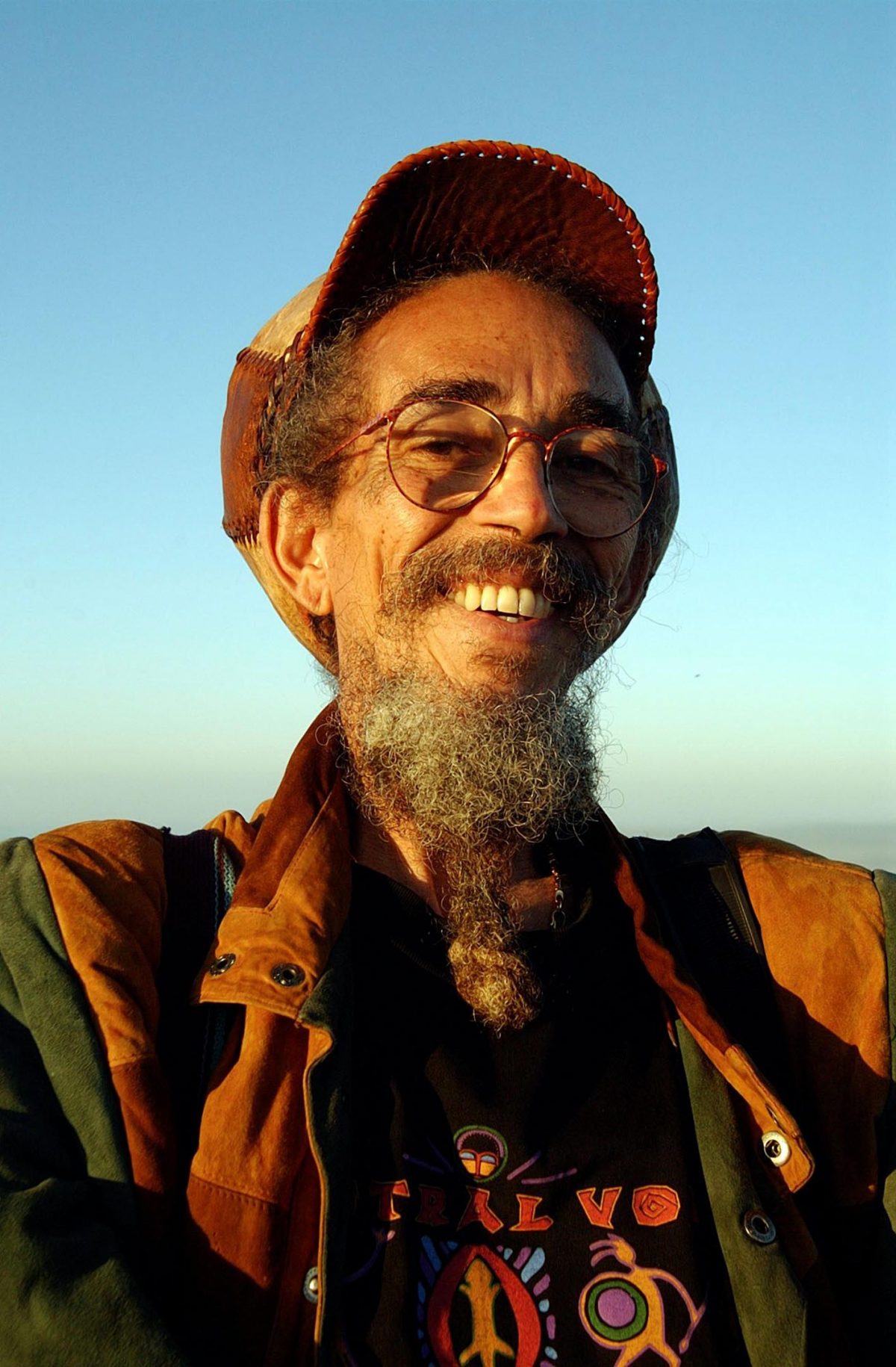

All West Indies cricket fans of the 1970s-to-2000s vintage know Colin Cumberbatch, the cricket photographer. ‘Jah B’ or ‘Bone’ as he is known throughout the Caribbean was a familiar sight at Test Matches and One Day Internation-als during home series. Frequently, he was also a member of the small Caribbean media contingent on overseas tours. Cumberbatch, his floor-length Rastafarian locks neatly tucked under his distinctive ‘crown’, could often be seen at the close of play crossing the ground, lugging his bag of cameras and tripod, pausing numerous times to engage with cricket aficionados.

A master griot with a perpetual smile, Cumberbatch has a unique style of relating his life experiences. Narratives on cricket matches are interspersed with travelogue anecdotes, history chronicles, and explorations of myriad subjects ranging from the servicing of adding machines to how to bid in the game of Bridge to the best Caribbean vegetarian restaurants.

A few years ago, he shared this yarn with a group of West Indies fans: “It’s lunch time, fifth day at the Lord’s Test, up in England, 1984. We chasing runs and looking solid. I left the spot where I was taking photographs and I gone over to the pavilion. When I reach the West Indies dressing room, the place buzzing. I notice Viv [Richards] sitting alone, looking like he pissed with the world. I know Vivi since he was ‘bout 15, 16 years old. I used to live next door to his brother Donald.” Born in British Guiana, Cumberbatch had migrated to Antigua in 1965, where his father had gone to work, to join his parents.

“I approach Viv, and ask him, ‘Why you vex so?Ah who do you?’,” the bard continued laughingly. He paused, casting a serious facial expression, before mimicking Viv’s response, whilst motioning with his hand, “Da one dey, you ….”

……………………………………………..

On 13th May, 1984, the twelfth West Indies Test team departed from Barbados for a highly anticipated tour of England, having just retained the Sir Frank Worrell Trophy after dispatching the visiting Australians 3-0. On their last visit, four seasons prior, the tourists had held on to the Wisden Trophy, winning the five-Test series 1-0, as the weather wreaked havoc that summer. The solitary victory, a two-wicket squeaker in the First Test at Trent Bridge, was fortunate to fall their way, after David Gower, running backwards at cover, dropped a spiralling skier off Andy Roberts, whose innings of 22 not out, was the critical difference in the end.

The First Test, at Edgbaston, was completed just after lunch on the fourth day, as the West Indies raced to their fourth consecutive victory. The margin of defeat, an innings and 180 runs, was one of the heaviest ever inflicted upon England at home. After dismissing England for 191, the West Indies compiled a mammoth total of 606, led by centuries from Viv (117), and Larry Gomes (143). Skipper Clive Lloyd, 71, Eldine Baptiste, 87 not out, and Michael Holding, 69, also contributed substantial scores. For Gomes, it was a significant return to form, after having lost his place in the team for the final three Tests of the Australian series.

The Second Test at Lord’s, cricket’s headquarters, commenced on Thursday, 28th June, with Lloyd winning the toss and inviting the hosts to bat. A keen tussle ensued over the first four days, as England battled gallantly after the embarrassing defeat in the initial match. England’s left-handed opening pair of Graeme Fowler and Chris Broad defied the fearsome West Indies attack of Malcolm Marshall, Joel Garner, Milton Small and Baptiste, with a century stand, a plank on which England failed to capitalise. Apart from Fowler’s maiden Test century, 106, and Broad’s debut innings of 55, only all-rounder Ian Botham’s knock of 30 was of any significance in the 286 total. Marshall was the pick of the bowlers, with six wickets for 85 runs.

In reply, the West Indies were soon struggling at 35 for three, with the openers, Gordon Greenidge and Desmond Haynes, and first down batsman, Gomes, falling victim to Botham. A fourth-wicket century partnership between Lloyd and vice-captain Richards appeared to be swinging the pendulum in favour of the visitors, when Richards was adjudged lbw to his Somerset County teammate, Botham. Richards’ dismissal for 72, the sixth lbw decision of the match, thus far, left the West Indies precariously poised at 138 for four. A vital seventh-wicket partnership of 40 between Marshall, 29, and Baptiste, 44, both of whom fell to Bob Willis, added some respectability to the West Indies score of 245. Once again, Botham dominated the highlight reel, becoming the first Englishman to take eight West Indies wickets in an innings in a Test in England.

At close of play on the Saturday afternoon, England were 114 for four, 155 ahead, with Allan Lamb, 30, and Botham, 17, the not-out batsmen. When the match resumed on Monday, the pair held the upper hand against the West Indies attack, taking their fifth wicket partnership to 128, before Botham was trapped lbw by his other Somerset teammate, Garner for 81, his highest score in a Test against the West Indies. When Lamb, having passed the century mark, accepted the umpires’ offer for light – 115 minutes had been lost earlier in the day due to similar conditions – 53 minutes before the scheduled close, England led by 328, with three wickets standing.

At the fall of England’s ninth wicket, Derek Pringle lbw to Garner – the Test record equalling 12th lbw decision of the match – 17 minutes into the final morning’s play, England Skipper Gower signalled the declaration. It was a tough assignment awaiting the West Indies. Score 342 to win the match, or occupy the wicket, for four and a half hours plus 20 mandatory overs, to avoid defeat. The bookmakers probably set the odds in favour of a draw, or a possible England victory if the cavalier West Indies threw caution to the wind in attempting a risky run chase, since no team had ever scored over 300 in the fourth innings to win a Lord’s Test. Defending the formidable target was a bowling attack of giants; the evergreen Willis stood 6’ 6”, Pringle, 6’ 5”, Neil Foster 6’ 4”, along with a pair of 6’ 2” dwarves, Botham and Geoff Miller, who were quite capable of restricting the scoring if plans started to go awry. Everything pointed towards the game petering out to a tame draw.

Four months earlier on the final day of the First Test versus the Australians at the jam packed Bourda ground, openers Greenidge and Haynes had launched an assault as the West Indies chased 323 in two sessions plus four overs. As the 20 mandatory overs began, the West Indies required 152, with all their wickets intact, and the heavy hitters, Richards and Lloyd padded up. However, Greenidge and Haynes spluttered in the final hour, and the match was called off with four overs remaining; the scoreboard reading 250 without loss, Greenidge, 120, and Haynes, 103.

On this occasion, Greenidge and Haynes began cautiously, playing themselves in, paying close attention to the fifth-day wicket. A boundary from Greenidge through mid-wicket set the score ticking along, as the BBC Television Commentary team of Ted Dexter, Jack Bannister, Jim Laker and Richie Benaud let the game unfold in front of the viewers’ eyes, calmly providing expert analysis and commentary of the contest, whilst duly noting the necessity for wariness.

The first 11 overs from Willis and Botham yielded 39 runs, nothing out of the ordinary, as the pair continued with their measured approach against the attacking field set by Gower, with Greenidge, in particular, punishing any short or loose deliveries. Just past the first hour, Haynes tucked a delivery from Pringle to short mid-wicket. Both batsmen started running, but Greenidge spied Lamb charging towards the ball, and shouted “No!”. Lamb swooped, picked up the ball and his underarm throw plugged the stumps, as Haynes scrambling in vain, was just short of his ground. Fifty-seven for one.

Gomes joined Greenidge, who was beginning to give a hint of his intentions. Two savagely executed boundaries off of Pringle’s bowling, one a menacing textbook square cut and the other a powerful straight drive, should have set off alarm bells in England’s camp. Having grown up in England, Greenidge was well tuned to the weather and pitch conditions, and here he was exploiting his knowledge and experience. A brace off Pringle brought up Greenidge’s 50, as the score moved to 77 for one. At lunch, the West Indies were 82 for one off 20 overs, with Greenidge on 54, having already struck ten fours.

The die was cast between lunch and tea, as Greenidge continued to go from strength to strength. Gomes in the supporting role continued to turn the strike over to the in-form opener. A drive to wide cover followed by a scampered single brought up a much deserved hundred for Greenidge. His century had taken 146 minutes and came off 135 deliveries, and was the backbone of the West Indies total of 149 for one.

A beautifully timed square drive by Gomes off Botham brought up the century partnership, as the runs continued to flow from the wilting England attack. Using his feet, Gomes drove Miller, bowling around the wicket, straight down the ground, Greenidge hopping out of the ball’s path, to bring up his 50, as the score climbed to 201. At tea, the West Indies were nicely perched on 214 for one, after adding 125 off 25 overs in the session, whilst striking 17 fours. Greenidge, 125, Gomes, 52.

Gower was confronted with a study in contrasts; two forces of opposing magnitudes in the right-handed Greenidge and left-handed Gomes. Two artists: one a sculptor, the other a landscape painter. The first plundering Gower’s attack to pieces with savagely executed strokes, the vicious thumps reverberating around the sparsely filled ground. The second effortlessly caressing the ball into the gaps, just as deliberate in destruction. It was only a matter of time now.

In the Caribbean, everything had ceased. People were glued to their television sets or transistor radios. History was unfolding; no one wanted to miss it. The floodgates burst open after tea, no white flag required. There was no stopping the rampaging Greenidge. Botham was nonchalantly hoisted for six over square leg. England supporters, fully appreciating the brilliancy of the innings, joined in the applause. A vicious square cut eluded a diving Gatting, crashing into the boundary advertising billboard, as Greenidge passed the 150-mark in 228 minutes. Pringle’s return to the attack was promptly greeted with two powerful drives, one of which forced the standing umpire to take evasive action. The 200 partnership rolled by, as the runs flowed in a torrent.

As the mandatory 20 overs commenced, the West Indies were 299 for one. Eight runs later, applause rippled around the ground as the second-wicket partnership reached 250, surpassing the West Indies’ record of 249 set by Lawrence Rowe and Alvin Kallicharran in March 1974 in the Third Test at Kensington Oval. Greenidge completed his first Test double century by hooking Foster for “a remarkable six,” the BBC commentator opined. There was a standing ovation from the appreciative crowd who were fortunate to witness only the ninth double century in a Test match at Lord’s.

With 13 runs required the BBC cameras panned the ground, capturing the celebrating West Indian fans in the stands, and pausing for a few seconds on the balcony of the West Indies dressing room. In the middle of the players, sat Viv, his massive forearms resting on the railing, lost in his thoughts, with his omnipresent chewing gum.

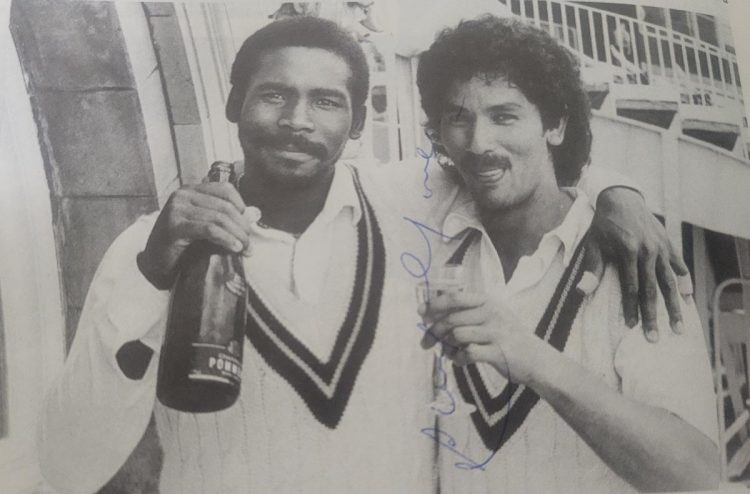

Gomes completed the honours, driving Botham through the covers. As jubilant supporters poured onto the ground, Greenidge grabbed a souvenir stump and started sprinting for the pavilion.

“What seemed to be an almost impossible assignment at the start of this innings has turned out to be an absolute doddle,” the BBC commentator summarised the famous West Indies victory.

Postscript

Greenidge’s innings of 214 included 29 fours and two sixes, while Gomes’ knock of 92 included 13 boundaries. Their record undefeated stand was worth 287.

Inexplicably, Man-of-the-Match Adjudicator Godfrey Evans, the former England wicketkeeper, awarded the prize jointly to Greenidge and Botham.

The West Indies went on to sweep the series, the first team to accomplish the feat in England.

During the West Indies first innings, the famous Topley incident had occurred. Twenty-year-old Don ‘Toppers’ Topley was employed as a young professional on the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) ground staff. One moment ‘Toppers’ was selling programmes during the Test match, the next, he was on the field as the 12th man, subbing for Broad. Fielding at long-leg, ‘Toppers’ made an incredible one-handed catch off Marshall, only to step on the boundary rope, and for it to be counted as six.

Cumberbatch never made it back to his spot and spent the rest of the afternoon on the West Indies dressing room balcony. And Viv’s response: “Da one dey..,.” motioning to GGs – Greenidge’s nickname among the players – “you ain’t see he dey in a mood? I ain’t gon get no batting today.” Poor Viv, he had to sit there all day with the pads on, knowing fully well that it was over since lunchtime.