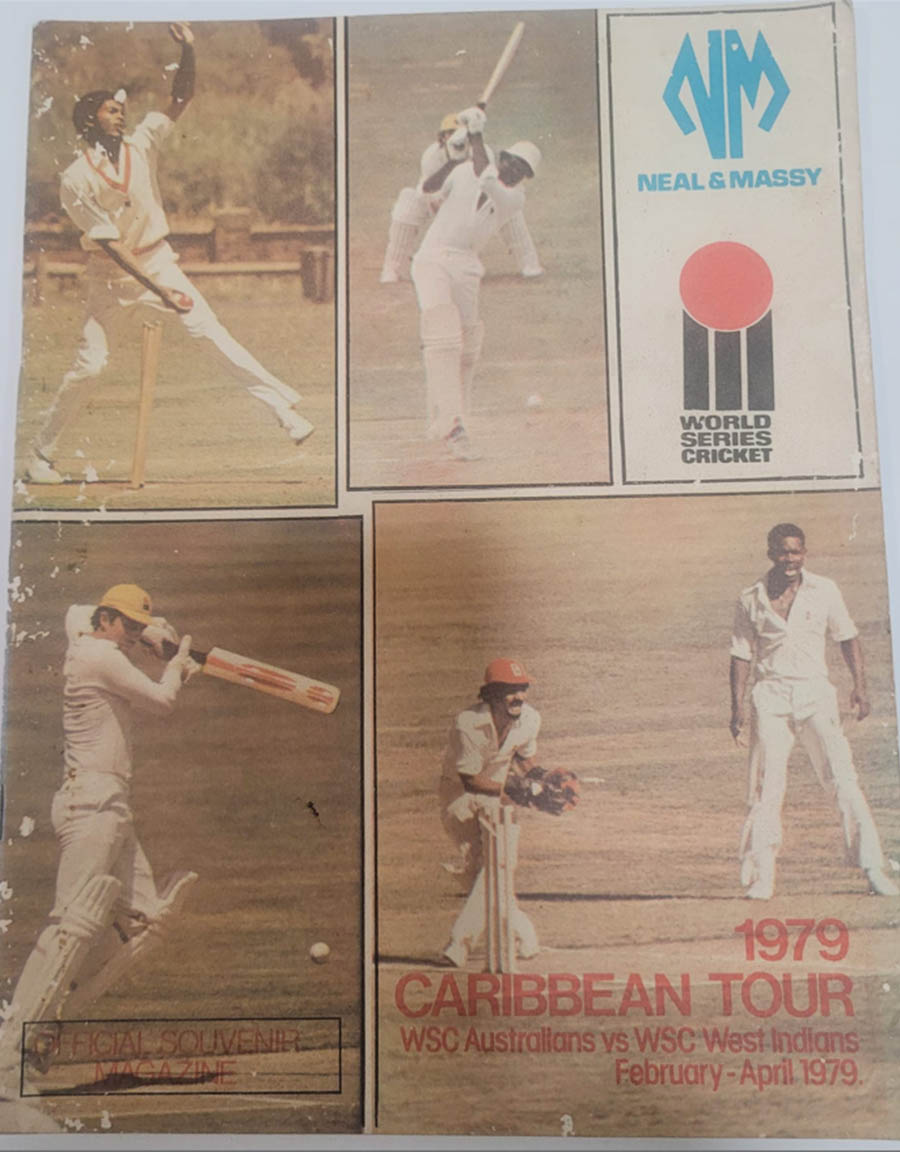

In this week’s edition of In Search of West Indies Cricket, the first of two parts, Roger Seymour looks at the preamble to the 1979 World Series Cricket season in the Caribbean

Origin of WSC

In May 1977, World Series Cricket burst onto the international arena like a tsunami approaching the shallow waters of the coast. (In Search of West Indies Cricket, SN, The Packer Revolution, February, 6th, 2016; The Game Changer, February 21st, 2016; Floodlights, helmets and pyjama cricket, 28th February, 2016). As a tsunami travels from the deep water of the open ocean its speed diminishes, but its energy flux, which is dependent on both wave speed and wave height, remains constant. As a tsunami slows, its height increases, an effect referred to as shoaling. Thus, unnoticeable at sea, a tsunami roars into landfall as a menacing gargantuan force. And so it was with Packer’s circus, as the English media referred to WSC in its initial phases.

A well-kept secret before the story broke, international cricket was never the same staid game which had been controlled by the old-school-tie-blazer-clad crowd from its inception. In a nutshell, Australian television tycoon Kerry Packer had decided to host his own cricket season after clashing with the Australian Cricket Board (ACB) over television broadcast rights. In 1976, his offer of AUS$1.5 million (which was eight times higher than the previous contract) for the broadcast rights for three years for Australia’s home Test matches was rejected by the ACB in favour of Australia Broadcasting Corporation’s (ABC) offer of AUS$210,000, in part due to the fact that ABC had been providing coverage for 20 years when commercial broadcasters had shown little or no interest. When Packer’s Channel Nine Television Network tried to secure the rights to the 1977 Australian Tour of England, ACB tried to foil his bid by recommending ABC to the England’s Test and County Cricket Board, despite their offer being only 14 percent of Packer’s. The television magnate eventually snared the contract by doubling his original tender.

Prompted by the idea of two Western Australian businessmen John Cornell and Alvin Robertson to host exhibition cricket matches, Packer conceived a plan to host a series of matches between the Best Australians and the Best of the Rest of the World, and duly set about organising the series and signing up the leading players.

When Packer’s concept became public knowledge, there was all manner of rejection and pushback by the cricketing establishment and the ICC proposed banning Packer’s recruits from Test and first class cricket. Packer attempted to negotiate a truce with the ICC, but the talks broke down after two hours. He then declared a war on the cricketing authorities, announcing, “It’s every man for himself, and the devil take the hindmost.”

World Series Cricket Pty Ltd, along with three signees, former England Captain Tony Grieg (who was relieved of the captaincy when his role as the lead recruiting agent for WSC became known), England fast bowler John Snow and Gloucestershire’s South African all-rounder Mike Proctor, then sought injunctions preventing the ICC and the TCCB from banning World Series players from Test and other first class cricket.

On 25th November, in London’s High Court, Justice Christopher Slade spent five and a half hours reading the 211 foolscap pages of his ruling, which he based on nine principal questions, finding in favour of the plaintiffs on all counts. Justice Slade noted that to ban cricketers from playing Test or county cricket because they had signed with WSC would be an unreasonable restraint of trade and an inducement to the players to break their contracts. He held that the proposed ban was void and costs, estimated at £250,000, were awarded to World Series Cricket Pty Ltd and the three players.

Justice Slade noted, “A professional cricketer needs to make his living as much as any other professional man.” He added that whilst he understood that the authorities were “dedicated lovers of the game,” acting in good faith, that was irrelevant when considering the legal issues.

WSC contracts

“I told every player, ‘This is a tough contract and you’ll do as you’re damn well told.’ ” – Kerry Packer

WSC’s contracts were not only demanding, but ironclad. ACB Treasurer Ray Steele stated, whilst giving testimony during the 31-day trial, that he was made to understand from World Series executives that “the only way a player could get out of a contract was to get pregnant.”

According to the contract players were required to: (1) On the direction of the promoter unless prevented by illness or accident or for any other reason satisfactory to the promoter play in the matches of a tour for which he is chosen by the promoter and will at all times play to the best of his ability and skill provided however that the player shall not be required to play for more than 65 days in aggregate of any tour. (Apart from the two days referred to in clause 4 (b) hereof) but subject always to the provisions of clause 5 hereof. (2) Punctually attend at such times and places as the promoter may direct for the purpose of playing the aforesaid matches or the practise or otherwise as the promoter may require. (3) Be at the venue at all times dressed in cricket uniform ready to commence play at least 15 minutes before the time for the commencement of play each day and thereafter throughout each such day. Other clauses detailed stringent requirements with regard to physical fitness, following specific arrangements to reside during tours, and participation in cricket coaching clinics, group photographs, television programmes for advertisements, tour news, promotional and publicity purposes.

WSC begins

The first World Series Cricket season played during the Australian summer of 1977/78 was not a resounding success in terms of public acceptance. Audiences were a bit skeptical of the product which was being played at non-traditional cricket venues such as the Victoria Football League Park, 15 miles outside of Melbourne, the Adelaide Football Park, seven miles outside the city centre, and the Sydney Showground, well known for hosting agricultural shows, harness racing and speedway (dirt track racing). WSC management elected to run the Super Test series head to head against the (traditional) Australia versus India Test series, and came out the loser in terms of attendance. WSC’s “Cricket Revolution” campaign promoting innovations of drop-in pitches, night cricket facilitated by floodlights, coloured clothing and white balls were yet to appeal to the Australians. On the field, the WSC West Indians beat the WSC Australians by a 2-1 margin in their Super Test encounters, and by 25 runs in the International Cup Series Final (40 overs competition). Viv Richards enjoyed a wonderful season, blasting 862 runs at an average of 86.2, including scores of 79, 56, 88, 123, 119, 177, and 170, in six SuperTests (inclusive of three for the World XI).

The second World Series Cricket season was a difficult one for the West Indians, who had to deal with a slew of injuries, loss of form by key players and a much better prepared WSC Australian XI, as they lost two of three Super Tests, with the other one drawn. However, they recovered to win the best of five International Cup Grand Finals by a scoreline of 3-1, after losing the first game.

Caribbean negotiations

Extract from the Kerry Packer Player Contract – “Clause 5. The player acknowledges that he is aware that the promoter plans to promote, organise and conduct from time to time series of matches outside Australia and he undertakes and agrees at the direction of the promoter to participate as a player in all or any of these series as shall be conducted during the said term subject to the promoter.”

Whilst Packer was waging war against the ICC and the TCCB in the High Court in London, he had hinted at taking his WSC outfit to England, and had also disclosed that there had been interest from the USA for his cricketers. The second WSC summer had begun with a two-week, pre-season tour of New Zealand that is best remembered for the extremely poor wickets and forgettable playing conditions. In hindsight, it is rather easy now to acknowledge Packer’s business acumen and foresight. The target for the first major overseas WSC venture away from Down Under, was the West Indies, the key rivals of the WSC Australians.

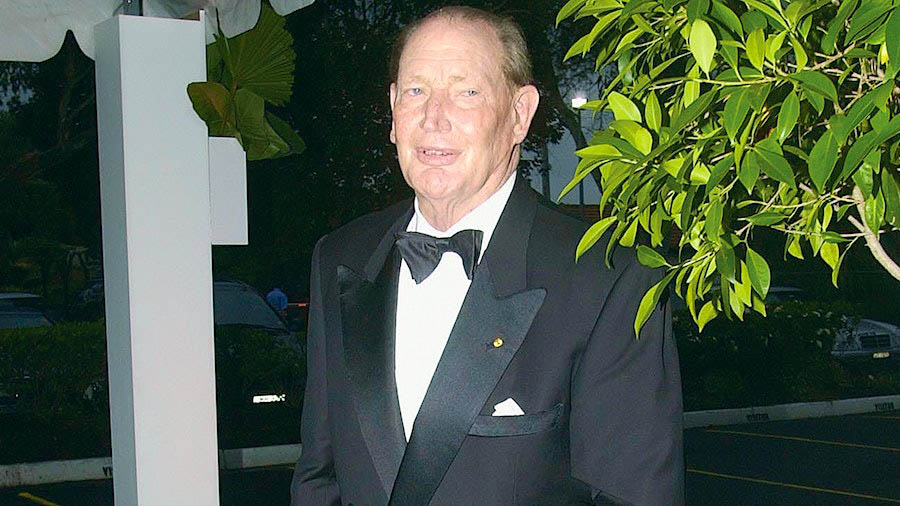

On Sunday, 16th April, 1978, the second day of the Fourth Test match of the West Indies vs Australia at Queen’s Park Oval in Trinidad, Andrew Caro, the newly appointed WSC Managing Director checked into the Trinidad Hilton Hotel which is located on a hilltop overlooking the iconic Queen’s Park Savannah. The irony of the lobby being on the top floor of the upside-down hotel would not have been lost on Caro. Everything within the world of West Indies cricket appeared to be inverted at that point in time; the series was unfolding as a drama in two acts.

The West Indies, with the full complement of Packer players, had ruthlessly swept aside the Australians devoid of their WSC core and now led by Bobby Simpson, who had been brought out of retirement, in the first two Test matches, by an innings and 106 runs, and by nine wickets, respectively, both times inside of three days. When the WICBC decided to replace Desmond Haynes, Deryck Murray and Richard Austin, in order to blood new players who would be available for the India tour scheduled for later in the year, Clive Lloyd and the remaining WSC players withdrew in protest. A second XI was hastily put together to play under Alvin Kallicharran, who had been ineligible to sign with Packer since he was contracted to Queensland, the Australian state side. With the two teams evenly matched, the Australians had surprisingly won the Third Test at Bourda on the fifth day, by scoring 362 for seven wickets. In dire straits at 22 for three, with Simpson dismissed, Australia recovered to score their highest fourth innings total to beat the West Indies. Now, after two days, the two sides were evenly poised; West Indies 292, Australia 290.

Caro was in Trinidad to seek WICBC President Jeff Stollmeyer’s mandate for a Supertest series in the Caribbean the following season. Stollmeyer was in a bind. The individual boards had agreed not to meet with WSC individually, but now they were all on the hook for the costs awarded in the High Court case won by WSC. Thirty-five thousand pounds was an enormous sum of money to the cash-strapped WICBC, now facing dwindling gates with their Packer players absent. The First Test had drawn crowds of 24,000, but now, at the same venue, attendance was between 3,000 and 5,000. A boycott had been organised by a faction calling itself the ‘Committee in Defence of West Indies Cricket’, and the placard carrying demonstrators paraded outside the Oval. While shouting slogans and protesting the board’s split with the Packer players, they were calling for the resignations of the WICBC and the selectors. The WICBC was desperate.

At a meeting at the Stollmeyer property on Monos, one of the Bocas Islands in the Gulf of Paria between Trinidad and Venezuela, the president indicated that the board was willing to defer a planned visit by New Zealand in March 1979, thus making the Test grounds in the Caribbean available for a WSC Tour. Stollmeyer, well aware of the vagaries of Caribbean tours – the weather, boycotts, protests – rejected Caro’s offer of the tour proceeds, insisting instead on a lump sum payment. The negotiators agreed in principle to meet in July in London after the ICC meeting, with Caro delegating Deryck Murray to act as the WSC agent to negotiate with local boards and sponsors.

Derek Parry spun the West Indies to a 198-run victory just after lunch on the fourth day, as the home side claimed only its second lien on the Sir Frank Worrell Trophy. The Fifth Test at Sabina Park, Jamaica, was abandoned as a draw on 3rd May, with 6.2 overs remaining and one West Indies wicket standing before an Australian victory. The crowd, upset at the dismissal of Vanburn Holder, began throwing bottles onto the field, forcing the Australians to run for cover, as the Jamaican police fired warning shots into the air. It was an embarrassing finish to a series marred by controversy, as the Australians were more than likely to win the game.

Caro and Stollmeyer met as planned after the ICC meeting at the Barclays Bank flat in Mayfair, London, where Stollmeyer, a banker, stayed when in England. The WICBC, after the Australian Tour, was basically insolvent, and Stollmeyer was asking for an ex-gratia payment of £35,000 – the board’s indebtedness to the ICC for the High Court burden – in return for approving the WSC Super Test series in the Caribbean.

When Caro called Packer to deliver the news that the WSC Caribbean Tour was on, he announced:. “It’s peanuts”.