Seemingly keen to be re-elected to office when the United States goes to the polls in November next year (the now increasing references to his age and his suitability for another tilt at the White House, notwithstanding) President Joe Biden is aware of the fact that a few eye-catching accomplishments on the foreign policy front are is unlikely to hurt his chances. In that context, he is more than likely to seize such opportunities to re-open Washington’s door to a long-standing strategic ally, Venezuela, which had been slammed shut by his predecessor and possible opponent for the White House, next year, Donald Trump. The sanctions that were imposed on Venezuela’s oil exports back in 2019 have been devastatingly effective. They have sent the Venezuelan economy into a virtual free fall, compelling the Maduro administration to reach out to Iran and Russia, mostly, for some measure of rescue. The help has been welcomed, but it has not been enough. Moscow and Teheran have been unable to fill the ‘holes’ created by the devastating impact which Washington’s embargo has had on Venezuela’s oil earnings, and by extension, on the country’s economy, as a whole.

No less devastating has been the incremental disassembling of sections of Venezuelan oil and gas sector, a function of both the substantive economic decline of the country and what, reportedly, has been a slew of corruption reports that has afflicted it and which, it seems, may have led directly to the departure of the country’s long-serving head of the oil sector, Tarecki El Assami, back in March this year at the beginning of a reported probe of corruption in the sector. Maduro’s problems do not, however, appear to be anywhere nearing coming to an end. These days, the day to day operations of Venezuela’s oil sector would appear to depend heavily on the contribution of the US oil company in Caracas to ‘help out’ with keeping sections of the country’s massive oil infrastructure ‘up and running’. CHEVRON’s presence in Venezuela persists with the approval of the Biden administration, a circumstance that positions Washington to pull the plug when it feels please to do so. Washington, seemingly, is still far from giving up mending fences with Venezuela as a strategic ally in the region on account of its impressive oil reserves, a 2021 estimate placing those at around 304 billion barrels, or enough crude oil to meet global consumption for roughly 8 years.

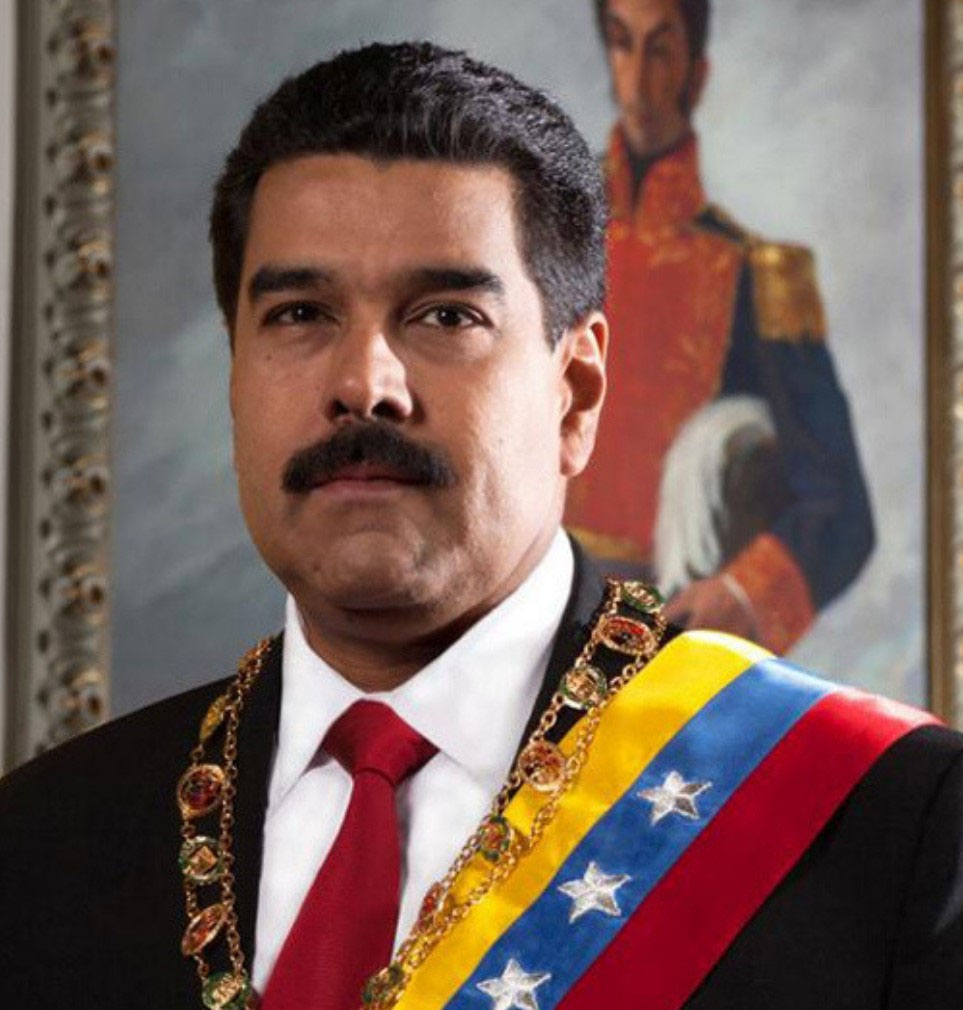

Statistics like these can hardly be ignored by a country bent on retaining its vaunted status as the world’s most vaunted superpower. It is this fact, overwhelmingly, that has persuaded the Biden administration not to remove the sanctions but also to keep the door ajar. Here, the US oil company CHEVRON’s continued presence in Venezuela, and more importantly, the role it plays in keeping the wheels of the country’s energy sector turning, is an example of Washington’s strategic thinking in the matter of its relations with a Nicholas Maduro administration which it regards as holding office illegally. Of late, however, Venezuela’s Dragon Gas Field, located offshore the Paria Peninsula, and reportedly containing between 2.4 and 3.2 trillion cubic feet of natural gas has come into the picture. Dragon has been the subject of a prolonged discourse between Caracas and Port of Spain, Venezuela seeing the recovery and refining of the gas as a timely potential boost to its threadbare economy. For its part, Trinidad and Tobago, the CARICOM front runner in the energy industry, needs the gas recovered from Dragon to boost its liquefied natural gas (LNG) and petrochemical industries.

The issue of cutting a deal that can be hugely beneficial to the economies of both Venezuela and Trinidad and Tobago, must however get past Washington’s insistence that it be the arbiter in terms of determining just where the funds accruing to Venezuela for the recovered liquefied gas goes. While the constant shuttling between Port of Spain and Caracas by T&T Energy Minister Stuart Young provides the optics in the ongoing efforts to close a deal, little can happen without Washington’s say so. Of late, Washington has appeared inclined to do a deal under which it may be prepared to further free up Venezuela’s oil and gas industry and allow for Dragon gas project to go ahead in exchange for Maduro agreeing to hold free and fair elections. General elections are due in Venezuela by 2024 to choose a President for a six-year term beginning on 10 January 2025 though whether Maduro is prepared to give Washington what it wants is an altogether different matter. Both Port of Spain and Caracas place a high priority on pushing ahead with the project, the former needing the liquefied gas to boost its liquefied natural gas and petrochemical industries while Venezuela sees the gas as playing a role in allowing the country access to cash flows.

It is Washington, however, that is considered the fly in the ointment with the Biden administration regarding the project as another lever that it can pull in pursuit of its effort to alter the political status quo in Venezuela. Whether Maduro is about to potentially harness the continuity of his presidency to a deal that includes even the removal of the wider sanctions imposed by Washington is unlikely so that, for the time being at least, and despite the persistent aura of optimism that has prevailed over the likelihood of the Dragon project proceeding, there is much that is still ‘up in the air.’