By Yongheng Deng and Shang-Jin Wei

By Yongheng Deng and Shang-Jin Wei

MADISON/NEW YORK – Bribery of public officials remains a major problem across the developing world and in some developed countries, too. Studies have repeatedly shown that graft impedes economic growth and development, prompting governments around the world to intensify their efforts to root out corruption. China’s anti-corruption drive stands out in this regard, having led to the arrest or indictment of hundreds of high-ranking officials, as well as more than a million lower-level government representatives, since 2013.

Corruption increases the cost of doing business, impeding economic efficiency and undermining fairness across the economy and society. But, given that bribery typically occurs under the table, estimating the extent and scope of illicit earnings is extremely difficult. One way to do this is to apply the permanent income theory, which establishes a link between household wealth and big-ticket consumer purchases.

In a forthcoming paper in Management Science, we and our co-authors employ this methodology to estimate Chinese government officials’ “unofficial” income. Analyzing data on home purchases and incomes in a major Chinese city between 2006 and 2013, we compare households with a government official to those without one. We then examine the relationship between the value of homes acquired and household wealth, accounting for factors like the official’s gender, age, and education level.

We find that, on average, Chinese officials’ so-called “grey income” amounts to 83% of their formal salary. Notably, this figure increases sharply with rank. For example, the unofficial earnings of low-level civil servants are just 27% of their official income. By contrast, for governmental division chiefs (zheng chu in Chinese administrative jargon), the ratio skyrockets to 172%. Strikingly, the off-the-books income of a director general in a government department (zheng ju) – on par with the mayor of a small or medium-size city in China’s administrative hierarchy – represents a whopping 424% of official compensation.

In principle, there can be two different types of corruption equilibria: one in which a few highly corrupt officials operate within an otherwise clean bureaucracy, and another in which corruption is widespread across the administrative system. Each of these scenarios affects the economy and society in distinct ways, requiring different anti-corruption strategies.

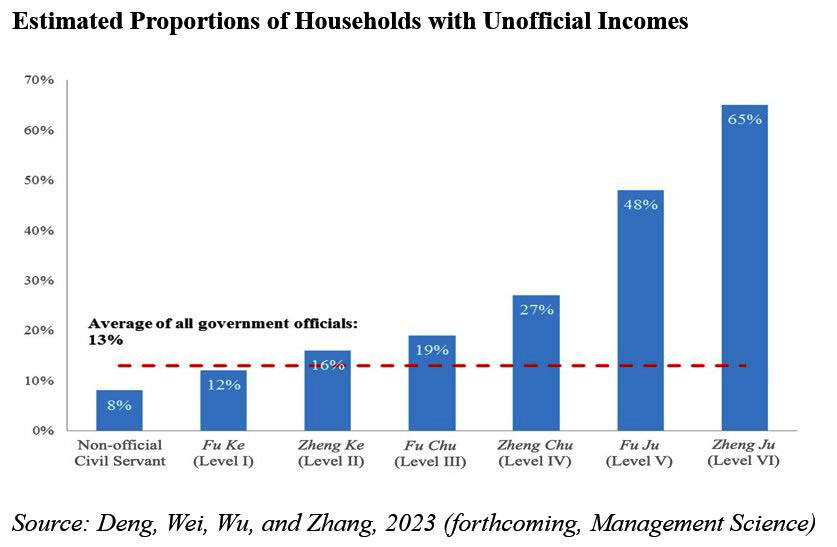

To understand which of these scenarios applies to China, we estimate the proportion of officials at specific administrative levels likely to have unofficial earnings. By comparing the value of home purchases in households with a government official to those without one, we find that 13% of the officials in our sample have an unofficial income. Importantly, this ratio also increases with rank. For example, our data suggest that roughly 8% of civil servants who are not in managerial roles receive significant undisclosed earnings, compared to 12% of low-level officials, 27% of the zheng chu, and 65% of the zheng ju.

Some have argued that public officials resort to bribes because their wages are low compared to what they could have earned in the private sector. To evaluate this claim, we consider factors such as education, work experience, age, and gender. Contrary to popular belief, we find no evidence that the government officials in our sample are underpaid given their education level and experience. In other words, inadequate government salaries are not the primary reason for the prevalence of bribery among Chinese bureaucrats.

The Chinese government’s sweeping anti-corruption campaign presents a unique opportunity to examine whether grey incomes stem from bribes. Our findings imply a significant correlation, as these unofficial earnings appear to decrease in areas where anti-corruption efforts have intensified, especially after the arrest or indictment of high-ranking local officials.

This suggests that the Chinese government’s anti-corruption measures have been at least somewhat effective. In addition to these efforts, introducing market-driven reforms, especially those that curtail government officials’ discretionary powers to issue licenses or allocate subsidies and other resources, could go a long way toward winning the fight against corruption.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2023.