By Nigel Westmaas

Outside of Africa and the Caribbean, nowadays Ghana and Guyana are often confused. This geographical ignorance aside, in the mid to later 20th century the two countries developed a remarkable and often overlooked bond and solidarity. This connection, which blossomed at a time when both nations were still under colonial rule, has regrettably faded into obscurity.

The connection between Ghana and Guyana, two nations with both similar and different colonial histories, originated in the Atlantic enslaved trade. During this dark period, countless enslaved Africans, many of them Akan, the largest ethnic group in Ghana, were forcibly taken from their homeland and deposited in Guyana. People of Akan descent were deeply involved in the resistance to enslavement, including Kofi, Accarah, and Accabre, all leaders of the 1763 slave revolt in Guyana.

History records that no matter how hard the European enslavers and colonisers tried to suppress them, African cultures, customs, and languages survived in the Americas, including in Guyana. African survivalism persisted in Guyana even after emancipation, without any significant population movement between the two countries. This legacy of slavery included language retention, complete with grammatical structures and philosophical underpinnings originating from Ghana and West Africa, which continue to influence key expressions in Guyana today. The Guyanese multi-disciplinary scholar Kimani Nehusi has extensively explored these oral traditions and retentions. Among them are Akan expressions and words such as “eh eh,” “senseh,” “putta-putta”, fu-fu, “conkie,”congo-tay”, “quashie”, “walah walah,” and many more. The concept of “box-hand” or “su-su” (described as a friendly cooperative savings scheme) well known in the African Guyanese community (as well as in other Caribbean societies) was active in West Africa and originally called esusu (among other descriptives) on the continent.

Ghana Day celebrations

Fast forward to the burgeoning anticolonial movement from the 1940s to the 1960s. Ghana’s independence on March 6, 1957, marked a new and pivotal moment not only in its own history but also in its relationship with other nations striving for self-determination, for which Ghana became a model. In the then British Guiana, news of Ghana’s independence ignited enthusiasm and solidarity. The Legislative Council of British Guiana officially conveyed its greetings and congratulations to the Parliament of Ghana. On March 1st, 1957 WOR Kendall moved a motion that encapsulated these sentiments:

“Be it resolved that this Council records its profound pleasure and satisfaction over the historic event which will take place on March 6, 1957, when Ghana will attain the status of an independent state within the commonwealth and desires that its greetings, congratulations and good wishes be communicated by telegram to the Parliament of Ghana.”

Esther Dey, one of only two women in the Legislative Council (the other was Gertie Collins), called for a public holiday to be declared on March 6 in honour of Ghana’s independence. Sugrim Singh, another member of the council, agreed, citing his close association with Kwame Nkrumah, the former anticolonial agitator turned Prime Minister of Ghana. Singh fondly recalled participating in anticolonial demonstrations alongside Nkrumah during their time together in London after World War II, events that united colonised peoples from Africa, Asia and the Caribbean, fostering solidarity among them within the imperial metropole. The Governor in Council also decided to permit any “officer or employee to be absent from work without loss of pay on March 6, in order to join in any celebration of Ghana’s independence.”

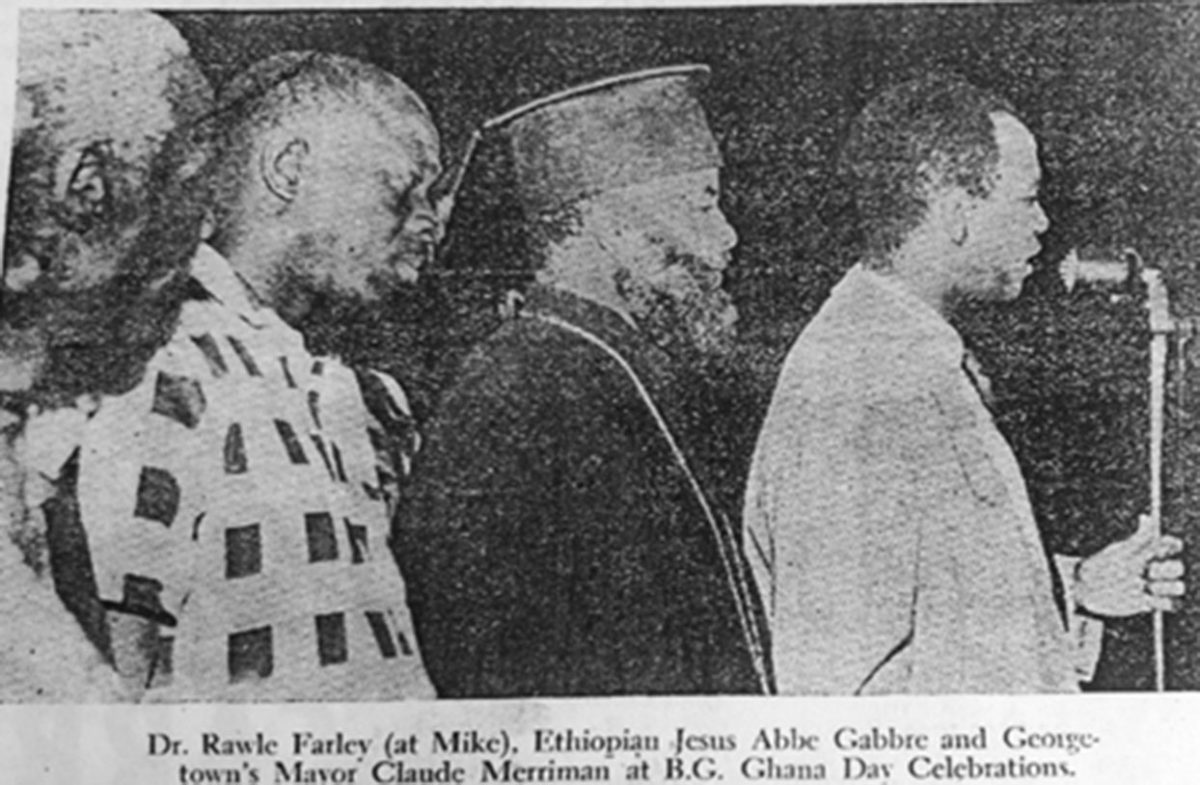

Unofficially, the League of Coloured Peoples, led by Dr Claude Denbow, organised a Committee for the celebration of Ghana Day which also included the African Welfare Convention. Those giving tributes on the appointed day included Denbow, Dr Rawle Farley, Jainarine Singh, Gertie Collins, Jessie Burnham, Georgetown Mayor Claude Merriman, and Ethiopian Orthodox Church priest Abbe Gabbre. There was a discordant note. Percy Armstrong, lead journalist of the Guiana Times magazine (and a critic of the Ghana Day celebrations) wrote sneeringly that the procession “snarled up traffic herding cops as they turned Guiana into Ghana.” All the same, the impact of Ghana’s 1957 independence on Guyana cannot be overstated. Ghana Day celebrations in Guyana became a symbol of shared aspirations for freedom and self-determination.

Two years later, the Ghana Day celebrations witnessed a remarkable expansion in scale. The Guiana Graphic’s March 7, 1959, edition documented an extraordinary turnout, predominantly women, with a crowd of approximately 20,000 people converging at Bourda Green to participate in the festivities organised by the People’s National Congress (PNC). This grand event exuded a proto-carnival atmosphere, marked by a vibrant parade adorned with cultural expressions, with many participants resplendent Ghanaian-inspired attire.

President Kwame Nkrumah and Forbes Burnham

Speakers at this Ghana Day celebration included prominent figures such as Georgetown Mayor Claude Merriman, John Carter, Hoosain Ghanie, Richard Ishmael, and LFS Burnham. With an eye on local politics, Burnham, the keynote speaker, assured the crowd that their “enthusiasm was indicative of their desire for independence for British Guiana.”

Amid the bustling preparations for the Ghana Day celebrations in Georgetown, a significant development occurred as the two prominent political figures of the colony, Cheddi Jagan and Forbes Burnham, received invitations to join the festivities in Ghana marking the country’s independence. What makes this episode even more noteworthy is that these two often adversarial political leaders set aside their differences and embarked on a joint journey to Accra. This outward show of unity not only served as a symbol of their endorsement of Kwame Nkrumah’s visionary ideals, but also highlighted Ghana’s efforts in advancing Pan-Africanism alongside growing anticolonial sentiment and action in the British empire.

Ghana’s putative diplomatic intervention in Guyana, 1964

By 1963, the focus on Ghana Day and black cultural events had significantly diminished, primarily driven by Guyana’s domestic political considerations. There were concerns that continuing to celebrate Ghana Day might be seen as racially insensitive and could impede the formation of a unified national party, particularly from the perspective of the PNC. Nevertheless, Ghana Day continued in less formal settings in rural black villages, indicating that an independent trajectory of black cultural consciousness was established in the society irrespective of formal political affiliation with the PNC. Still, the enduring legacy of Ghana’s independence and its impact on Guyana’s journey toward self-governance remained palpable. In early January 1964, Ghana’s UN envoy Alex Quinson Sackey met with Premier Jagan, paving the way for a full-scale Ghanaian delegation to Guyana the following month.

President Nkrumah and Dr Cheddi Jagan

Nkrumah’s involvement in Guyanese affairs, perhaps encouraged by his Ghana-based prominent Guyanese advisers, came in response to an appeal by Dr Jagan to facilitate negotiations between the People’s Progressive Party (PPP) and the PNC amid considerable racial and political tension. Nkrumah appointed a special envoy, Professor W E Abraham (University of Ghana), along with a team to mediate between the PPP and PNC. The other members of the Ghanaian delegation were Sam Morris, a personal aide to Nkrumah, Mr Lomotely, TK Makonnen and Nana Kobina Nketsia. The delegation’s efforts were short-lived. There was intense pushback, with the delegation meeting resistance and skepticism.

The Evening Post wrote that any Ghanaian mission “can only advise on matters concerning a dictatorship, a police state and suppression of rights, but they are incapable of advising on matters of peace and goodwill.” That “incapacity” for the Post was the perceived anti-democratic moves by Nkrumah’s government at the time. For his part, Premier Jagan complained about the hostility of the press and the ambivalence of the PNC to the mission. He wrote: “the PNC leadership as usual, remained ambiguous. While in public it welcomed the mission, in private it opposed the visit. This was why the hooligan elements mobilised by the United Force against the mission were not criticised by the PNC”. The complexities of the situation highlighted the challenges of external diplomatic involvement in a sensitive internal political climate.

Pan-Africanist imperatives and solidarity: The Roles of Ras Makonnen and other Guyanese

Not to be overlooked in terms of direct influence in Ghana for the Nkrumah Pan-Africanist project was Guyanese Ras Makonnen, a stellar advocate of Pan-Africanism. Formerly George Nathaniel Griffith, Makonnen changed his name in 1935 out of solidarity with Ethiopia after the Italian invasion of that year. In 1937 he migrated to Britain from the US, where he first met Nkrumah, who was then a student. Along with CLR James, George Padmore, and John Henrik Clarke, Makonnen is said to have influenced the young Nkrumah toward the path of Pan-Africanism. Makonnen would later resume the links with Nkrumah as an operator of restaurants in Manchester, partly to support black radical activism. Makonnen also ran a nightclub and a bookshop, and rented homes exclusively to blacks during his long sojourn in England.

Generously, he donated £5,000 toward building a home for abandoned children fathered by black servicemen with white women who did not wish to keep their “coloured babies”. Notably, one of Makonnen’s employees in the restaurant was Jomo Kenyatta (later President of Kenya). After independence, Makonnen moved to Ghana and worked closely with Nkrumah who, in 1960, named him Director of the African Affairs Centre – established to promote and coordinate Pan-Africanist activism around the world. Makonnen was imprisoned after Nkrumah’s overthrow in February 1966, but was released at the urging of his friend Jomo Kenyatta. He then migrated to Kenya where he became a citizen and later a government adviser.

Another notable Guyanese, the author and activist Jan Carew, maintained a close working relationship with Nkrumah and other renowned individuals, including Malcolm X, whom he had met in London. Carew held a pivotal role as the head of Nkrumah’s Publicity Secretariat. In his autobiography, “Episodes in my Life,” Carew recounted forewarning Nkrumah about the brewing troubles in Ghana. Unfortunately, Nkrumah appeared irritable during their conversation on the matter. Not long after this exchange, Nkrumah, while abroad on a visit, was ousted from power in a military coup. Like Makonnen, Carew was detained in the aftermath of the coup. However, due to widespread protests for his release both in Guyana and from pan-African groups and individuals worldwide, Carew was eventually deported to London.

Another Guyanese to engage with Nkrumah was Moses Bhagwan. As head of the PYO (Progressive Youth Organisation), Bhagwan in 1965 attended a youth conference in Ghana, where he met Nkrumah.

Eusi Kwayana (then Sidney King) of ASCRIA (African Society for Cultural Relations with Independent Africa) was in Ghana between late 1964 and 1965 as part of a nine-nation tour of Africa (the other countries on his itinerary were Nigeria, Ethiopia, Mali, Liberia, Kenya, Zambia, Sierra Leone, and Tanzania) and told the press that “Ghana was the most politically active of the countries he had visited.” He said that Ghana’s political vibrancy was due to thorough organisation and because it was one of the countries that practised socialism in the African context. While in Ghana, where he met with Nkrumah, Kwayana attended a lecture by Che Guevara who was in the country at the time. A member of the PPP leadership, Brindley Benn, also travelled to Ghana in the wake of Kwayana’s visit.

Modern connections

Formal diplomatic relations between Ghana and Guyana were established on May 14, 1979. Over the decades, this diplomatic partnership has woven a rich tapestry of cultural, political, and diplomatic exchanges, connecting not only the leaders but also the citizens of both nations.

During the 1970s and 1980s, both Guyana and Ghana were active participants in the Non-Aligned Movement, a group of countries that sought to maintain their independence and neutrality during the Cold War, while also promoting economic development, social justice, and decolonization. Ghana supported national liberation movements in Africa and elsewhere during this period, providing both moral and material support to those fighting for independence from colonial and repressive regimes, albeit nowhere near the scale of the Nkrumah era.

In June 2019, President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo of Ghana embarked on a state visit to Guyana, where he received a warm welcome at the Cheddi Jagan International Airport by President David Granger, accompanied by a military honour guard. In 2021, Guyana’s Vice President Bharat Jagdeo reciprocated the visit by travelling to Ghana, engaging in high-level talks.

Of more recent vintage the Ghana Chamber of Commerce held a three-day conference in Guyana in August (2023) on collaboration on the oil and gas sector between the two countries. This collaborative effort is set to alternate between the two countries.

Additionally, Ghanaian musician Livingstone Etse Satekla, known by his stage name “Stonebwoy”, and known for his Afrobeats music genre performed at the annual Emancipation commemoration event at the National Park organised by the African Cultural and Development Association.

Indeed, the historical bonds that unite Ghana and Guyana, forged through the crucible of enslavement and independence struggles, have withstood the test of time. From Ghana’s declaration of independence in 1957 to the subsequent diplomatic interventions and cultural exchanges that have followed, the relationship between these two nations (and meetings of their respective nationals) has continued to thrive.