The language of chess has manoeuvred itself into many other pursuits. You might hear reference being made to a “pawn”, meaning an insignificant person. The word is much used in politics, military engagements and foreign relations. Then there are “strategic planning”, “opening phase”, “tactics”, “sacrifice”, strategy, and “endgame”. These words and phrases relating to the game of chess are in everyday use. People use them because the standards of success and failure in chess are strict. If your decisions are flawed, your position or situation deteriorates and the pendulum swings toward a loss or failure; if they are good, it swings toward a victory or success.

The language of chess has manoeuvred itself into many other pursuits. You might hear reference being made to a “pawn”, meaning an insignificant person. The word is much used in politics, military engagements and foreign relations. Then there are “strategic planning”, “opening phase”, “tactics”, “sacrifice”, strategy, and “endgame”. These words and phrases relating to the game of chess are in everyday use. People use them because the standards of success and failure in chess are strict. If your decisions are flawed, your position or situation deteriorates and the pendulum swings toward a loss or failure; if they are good, it swings toward a victory or success.

According to former world chess champion Garry Kasparov, “Every single move reflects a decision, and with enough time you can analyze to a fine certainty whether each decision you made was the most effective”. The simple truth is that if you make good decisions, you will succeed; make bad ones, and you will fail.

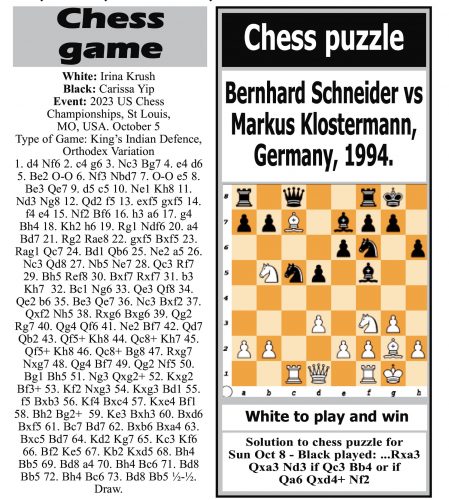

The truest tests of skill and intuition come when we aren’t sure what to do, or whether we should do anything at all. In the puzzle section of this column, I usually indicate whether White or Black would play and win. Such a pronouncement helps the solver of the puzzle. Immediately, the person knows there is a solution. It is not framed as a multiple-choice answer, nor is the phrase ‘none of the above’ included. Kasparov tells a story surrounding this theme about when he was world champion. He said that in 1987 he was invited to a special reception in Frankfurt held by Atari. “All of their managers were there, and the Master of Ceremonies was the head of their German division, Alwin Stumpf,” he continued. “It was an informal and entertaining evening where we discussed politics as well as chess and computers. In fact, I earned the friendly condescension of most everyone with my prediction that as a consequence of the changes in the USSR, the Berlin Wall would soon fall, perhaps in as little as five years. ‘A fine chess player,’ everyone said, ‘but he doesn’t know anything about politics!’ As it turned out, my forecast allowed three years too many. After the banquet was finished, Herr Stumpf took the microphone and grandly pronounced that we [were] about to see something extraordinary: he had seen me perform an amazing feat on television and now I was going to do it in person.”