British Guiana (Guyana), a colony of Britain continuously from 1803 to 1966, was consistently determined by the policies of the Colonial Office concerning the colony’s borders and territorial integrity. In the pre-Second World War era these policies were shaped by economic considerations and negotiations amid the challenging backdrop of the 1930s in Europe, marked by the rise of Nazi Germany and the subsequent Jewish expulsions from that country.

The “Jewish colonisation scheme,” which emerged through what can only be described as colonial manoeuvring, was the latest of a number of these peculiarly titled plans in Guyana. There were four other notable colonisation schemes, including the so-called “Indian Colonisation Scheme” (also called the Nunan-Luckhoo scheme) proposed in 1919, which aimed at immigration from India to Guyana. The plan called for “the introduction over a four-year period of 7,500 families from India.” While this first colonisation scheme initially generated significant controversial interest, it gradually lost momentum due to financial constraints, and opposition from local circles and in India.

The second initiative, known as the “Colonisation Scheme of 1928,” arose from the recurring labour shortages in the country and the reluctance to offer fair wages to workers. The designated settlement areas included the North West District and Bush Lot, Essequibo. While it was not aimed at any specific immigrant group, the plan did yield concrete outcomes, but as scholar James Vining (1978) notes, “the results were far from the ambitious project envisaged in 1928 by Governor Guggisberg”.

The third effort, the proposed “Assyrian Colonisation Scheme” of 1934, aimed to relocate Iraqi-Assyrian refugees forced to flee Iraq, to Guyana, a result of an historical outcome that led to “settlement” by the League of Nations. The Rupununi district was envisioned as the “new home” for displaced Assyrians. However, financial constraints primarily contributed to the eventual stagnation and failure of the Assyrian scheme.

The fourth is the “Jewish Colonisation Scheme”, the focus of this essay.

The fifth and final scheme in Guyana, during the immediate post-war period of 1947-48, similarly faltered. This unsuccessful plan which included British Honduras (Belize) and British Guiana (Guyana) did not specify any particular immigrant group but we can assume that Jewish immigration was still on the table as the commission recommending the scheme mentioned “the problems of re-settling European refugees who could not be repatriated after the war.” In this scheme the Kanuku mountains were identified as a potential settlement area.

Background

This outline, as indicated, delves into the proposed plan of establishing a Jewish colonisation initiative in Guyana as a potential resolution to the persistent Jewish question in Europe. It further emphasises the involvement of various stakeholders, most notably the United States.

The political reflexes of Britain over Jewish immigration were acutely intertwined with the historical context of the British mandate for Palestine, dating back to the League of Nations that arose out of the Paris Peace Conference of 1919-20. The British assumed responsibility for the area from 1920 to 1948, with the 1922 mandate containing 28 articles.

Prior to World War II, strict immigration policies of possible host countries resulted in a limited number of European refugees leaving the continent in the wake of the rise of Nazism in the 1930s. The massive attack on Jewish property and persons called Kristallnacht (night of the broken glass) throughout Germany in November 1938 precipitated a more urgent reaction to the Jewish refugee issue.

The British White Paper’s proposition (May 1939) of the Jewish project in Guyana stemmed from the dire situation of the Jewish population in Nazi Germany in the 1930s, alongside the reluctance of European powers to confront this crisis. The White Paper stipulated “that only 75,000 Jewish immigrants would be allowed to enter Palestine over the course of the next five years (10,000 a year, plus an additional 25,000)”. The White Paper promised a Jewish state but also “promised to set up an independent Palestinian state within the next ten years.”

Across the ocean, the Roosevelt presidential commission played a significant role in this effort, with Roosevelt initially favouring Africa, particularly Angola, as the most viable option for settlement of the Jewish refugees. The irony was palpable. Here was an immigration scheme aimed at aiding Jewish refugees from Europe but America did not want them. Further, antisemitism in the United States in the 1930s was at a premium and there were influential individuals and lobby groups that supported Nazi Germany. Moreover, these refugee initiatives highlighted the lack of genuine commitment toward the local populations in the empire zones. This absence encompassed political, diplomatic, economic, and technical support for those who were expected to accommodate the influx of immigrants.

British colonial outposts along with countries under American imperial influence were considered for potential Jewish settlement. These included Kenya, Northern Rhodesia (Zambia), Tanganyika, the Philippines, Angola, Uganda, the Dominican Republic, and Ethiopia. The Dominican Republic appeared to favour large-scale Jewish immigration, but other countries most capable of accepting significant numbers of refugees declined to open their gates to any Jewish refugee plan including Colombia (listed as turning down 10,000 German refugees), Chile, Ecuador, Paraguay, Shanghai (China) and Peru. Notably, the United States itself was reluctant to admit Jewish refugees beyond a certain quota.

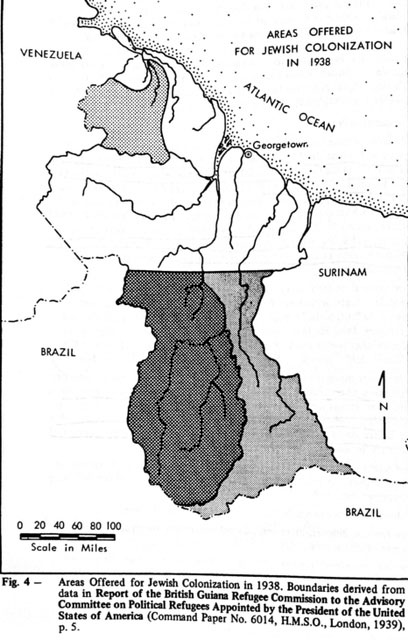

(Areas earmarked for the ‘Jewish Colonisation Scheme’ are clockwise from the top, Northwest District; East Berbice-Corentyne; and the Rupununi)

Proposed settlement and reactions

The Roosevelt Refugee Commission surmised that there was a vast expanse of rich, fertile black soil in Guyana’s allegedly unexplored interior. The commission unveiled a roadmap that could potentially reshape the future of British Guiana and solidify its role in providing sanctuary for those in need.

The United States, represented by President Roosevelt, appointed a six-man commission to examine the Guyana proposal. The “mixed Anglo-American commission”, fully titled the “British Guiana Commission to the President’s Advisory Committee on Political Refugees”, visited Guyana, arriving by boat in February 1939 with the mandate to “assess the viability and feasibility of large-scale colonisation in British Guiana for involuntary emigrants of European origin, including an estimate of the approximate number that could be resettled.” Lt Col Arthur ‘Art’ Williams, the American aviator who pioneered Guyana’s civil aviation was reported in the Hansard of July 21st, 1939, as flying aerial reconnaissance on behalf of the Royal Commission and a “Jewish Commission”, the latter most likely being the one appointed by Roosevelt.

The report was completed in May 1939. In response to a parliamentary question, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain articulated the government’s position, welcoming the British Guiana report and extending an offer to lease potentially suitable lands in the interior on favourable terms for refugee settlement.

The commission’s report on the prospective “white” Jewish settlement in Guyana outlined over 15 significant findings and recommendations. Particularly, Vining (1978) underscored the following (abbreviated) points:

● The climate does not hinder the possibility of white settlement.

● There are significant areas of arable soil suitable for immediate and permanent cultivation.

Establishing a transport route poses no insurmountable challenges.

The existing populace of the colony would embrace immigration by individuals of European descent.

British Guiana, particularly south of the 5th parallel north latitude, holds promise for substantial settlement by European immigrants.

An experimental village, serving as a prototype, should be developed in the Rupununi Savannah.

Approximately 3,000 to 5,000 people are projected to be necessary for the initial year of trial settlement.

To ensure an ample meat supply for the settlers until they achieve a certain level of self-sufficiency, it is advisable to explore the option of acquiring the assets of the Rupununi Development Company.

According to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, the designated area encompassed “36,300 square miles, spanning from 5 degrees north latitude to the western and southern borders with Brazil and the eastern border with Suriname. An additional 4,600 square miles in the North-West District was also included.” In short, the Rupununi, East Berbice along with the North- West district as shown in the image above.

The Refugee Commission’s report appeared simultaneously in Britain and the United States in May 1939. AJ Sherman, in his book “Island Refuge” wrote that initial reactions to the report “on the part of both refugee organisations and the press were at best tepid.” The Guyana refugee proposal also encountered Zionist opposition especially from Rabbi Hillel Silber of Ohio among the most outspoken of the critics. One Jewish group “assailed the report for excessive optimism, and for its potential diversion of material and human resources from Palestine.”

Similarly a letter in the Times by one AJ Schwelm, reportedly an expert on colonisation, “whose authority to speak on the subject was termed ‘unquestionable’” argued that European settlement in British Guiana was impracticable and “doomed to failure.”

Locally, the issue was raised in the Guiana legislature when Theophilus Lee, a member of the body, attempted to question the scheme. The brief exchange that followed provided an indication of the dismissive approach that the local governing bodies and authorities had toward the scheme, which belied one of the Refugee Committee’s findings. The committee had alleged that the people of Guyana were receptive to the settlement of Europeans.

Mr Lee: I do not know whether I am quite in order, but I would like to find out from government what is being done with respect to the Jewish Settlement Scheme for this colony (laughter).

The Chairman: I do not know if the Hon Member is really serious about that question

Mr Lee: Quite serious, your Excellency. As far as I know, this company has been subsidised because it would provide an easy means of getting to the interior.

The Chairman: The Hon member was misinformed.

But there was obvious support for the scheme from the British and American governments and other voices. In late 1938, a report from the Jewish Telegraphic agency appeared hopeful about the possibility that “British Guiana could easily absorb, and would welcome the settlement of 500,000 Jewish refugees, according to an article published in the local Daily Chronicle …co-authored by Theodore Orella, stock raiser, and Vincent Roth, former high ranking civil servant.” The Chronicle report seemed so starry-eyed that it appeared to ignore or deprecate local agricultural talent while lauding the work of the Jews “in turning sandy Palestinian wastelands into fertile orange groves,” going on to assert that Guyana “would profit greatly if Jewish refugees were to apply their industriousness to the fertile Essequibo valley.”

Meanwhile, Dr Joseph Rosen, leader of the American Jewish Agricultural Corporation, expressed optimism, asserting that among “all the territories across various parts of the world being considered as potential sanctuaries for victims of oppression in Europe, the British Guiana proposition ‘appears to align closely with our criteria.’” This sentiment reflected an expectant outlook, underscoring the perceived alignment between the requirements of the Jewish community and the attributes offered by the potential settlement in what was British Guiana.

Conclusion

Ultimately however, the Jewish Colonisation Scheme for Guyana was abandoned due to the eruption of war in Europe on September 1, 1939.

In October 1939, merely a month after the invasion of Poland by Hitler’s forces, sparking the onset of World War II, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency disclosed that the project, initially scheduled to commence in the autumn, had been “temporarily suspended”, and this was conveyed to the House of Commons by Colonial Secretary Malcolm MacDonald. With the escalation of the global conflict, the exigencies of the war effort eclipsed the prospects of such an extensive and ambitious resettlement project and any future realisation.

As recorded by history, the full horrors of the Holocaust in Europe had already commenced by 1941, marking the systematic murder of Jews, the Roma people, and other targeted groups. What often goes unnoticed is the direct connection between the methodologies employed by the Nazis in Europe and their prior experimentation of mass extermination on the Herero and Nama people in Southwest Africa and Namibia. This atrocity, which took place during 1904-1905 under the leadership of German General Lothar von Trotha, had resulted in detailed plans for a European genocide of African peoples that was coopted by the Nazis. These gruesome strategies were later adapted and refined by the Nazis in their pursuit to exterminate the Jews of Europe.

For its part, the original British colonisation plans for the territories claimed within the empire embodied all the facets of “settler colonialism.” These plans were accompanied by the concept of a “civilising mission,” reflecting the ambitions of British colonialism and its dismissive attitude toward local perspectives on land rights. This broad interpretation of the term “colonisation” effectively represented a form of double British colonisation, serving diverse endeavours, including the Jewish scheme as pursued in the case of Guyana, which ultimately played a role in the controversial establishment of the state of Israel in 1948 in Palestine.

For those interested in delving into counterfactual history, an intriguing question arises: what might have been the implications for Guyana (and indeed the Middle East) if the British colonisation plan of 1939 for Jewish immigration had materialised?