Prologue

“January 24, 1935 – First day of the Second Test Match [West Indies versus England at the Queen’s Park Oval, Trinidad]: Radio Station VP4Y6 will broadcast Test Cricket for the first time ever in the West Indies. There will be reports at the lunch and tea intervals, and the last hour of play will be carried as live ball-by-ball commentary, followed by a summary of the day’s play. Listeners as far as St Kitts, St Vincent and parts of BG [British Guiana] are expected to receive the broadcast.” (Excerpt from ‘Standing Up to the MCC’ – In Search of West Indies Cricket – 8th May 2016.)

On 23rd September, the Caribbean Premier League (CPL) Final was held at the National Stadium Providence and televised around the world to an estimated audience of 500 million. Today, it is taken for granted that whenever there is international cricket in the Caribbean, one can click on the remote control or swipe one’s iPhone, and voila!! – there’s the cricket telecast. It wasn’t always like this.

For seven decades, West Indies cricket fans had to suffice with the medium of radio for broadcast coverage of Test matches and ODIs in the Caribbean. Some of the territories had their own television stations, such as Trinidad and Tobago Television, which filmed matches in their respective territories. These recordings, which weren’t of the highest quality, were never relayed live, and often just utilised for snippets in local newscasts. In 1989, edited highlights of the Indian Tour of the Caribbean were transmitted back to India on a nightly basis.

Given the advent (in June 1980) of the West Indian juggernaut steamrolling other Test cricket nations, one might have assumed that televised broadcasts of live cricket from the Caribbean would have followed the natural progression of events. Surprisingly, there were no interested parties until mid-1989.

TWI and Sky TV

The International Management Group (IMG) was founded in 1960 by Mark McCormack, a Yale-trained American lawyer. The savvy McCormack, having recognised the value of celebrity endorsement to commercial enterprises in the television age, became a leading pioneer in the sports agent business. As IMG expanded rapidly, McCormack established a television company, Trans World International (TWI) in 1967, which eventually became the biggest producer of televised sport in the world. In mid-1989, IMG was the marketing agent for the West Indies Cricket Board of Control (WICBC) at the time, TWI bought the television broadcast rights for 1990 England Tour of the Caribbean from the WICBC for an undisclosed sum.

On 5th February, 1989, Sky Television, owned by Rupert Murdoch, the Australian media magnate, circumvented British ownership laws by renting space on the Luxembourg-based Astra satellites, and began broadcasting on four channels, with direct-to-home reception in the UK. As far back as 27th June, 1983, when the shareholders of Satellite Television agreed to a £5 million offer to sell 65% of the company to Murdoch’s News International, he had described cable and satellite television as being “the most important single advance since [William] Caxton invented the printing press [in 1476]”.

Today, Sky Sports is synonymous with the highly successful English Premier League (EPL), but back in mid-1989, Sky was bereft of content, and as David Hill, its then Director of Sport, explained, “TWI first came to us in the middle of 1989 to say they had the rights and the wherewithal to cover the series and to inquire whether we interested. Interested? We just about leapt down their throats.”

Once the parameters of the TWI and Sky venture were agreed upon, a series of preparations were set in motion to ensure that for the first time in the history of West Indies cricket, every ball bowled in a Test series and the One Day Internationals (ODIs) would be transmitted live around the world. In November, Producer Gary Franses and three colleagues visited the Caribbean on a pre-planning trip for what he would later describe as “the biggest single travelling outside broadcast ever mounted by a British company.”

It was an enormous operation which required detailed planning and execution. A Convair transport aircraft leased from Caricargo, a Caribbean airline, shuttled 70 cases of equipment and a group of over 30 producers, technicians, cameramen, commentators and scorers throughout the region. TWI recruited most of the personnel, while Caribbean Broadcasting Union (CBU) stations arranged for half-dozen cameramen and technicians. Amongst the hundreds of pounds of equipment were two miles of cables, seven cameras, three slow-motion replay machines, and computers.

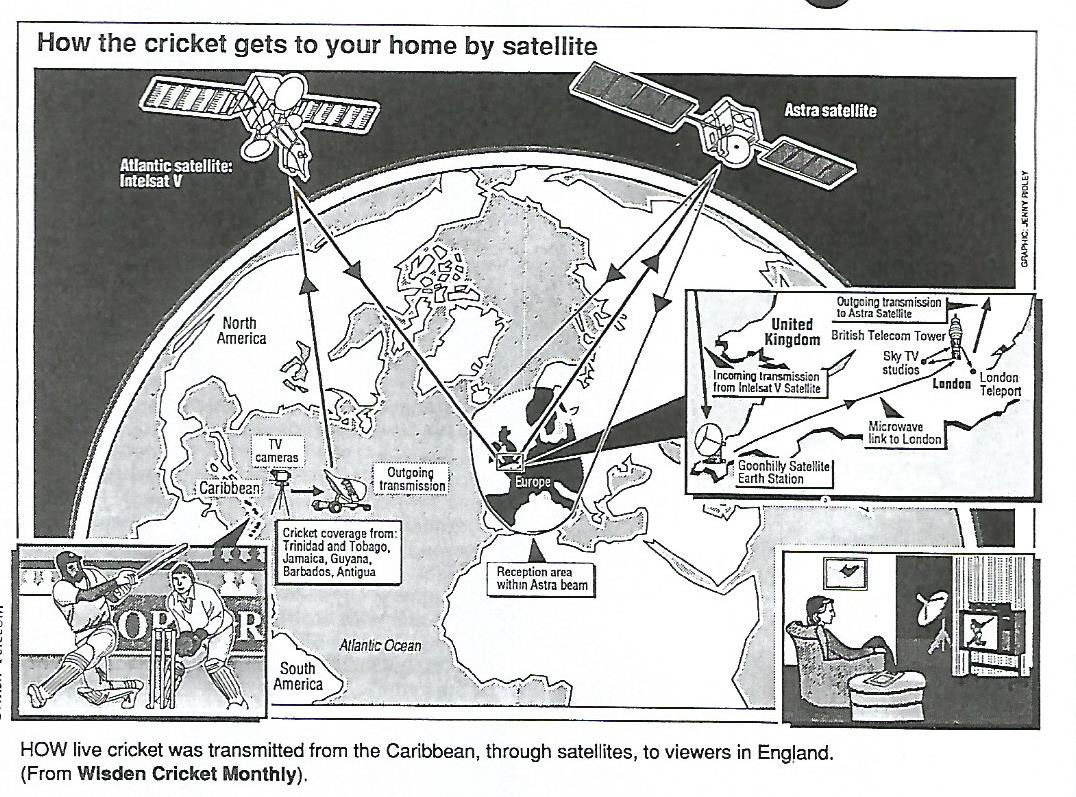

In Jamaica, Trinidad and Barbados the feed from the grounds was relayed to the respective existing satellite earth stations, while in Guyana and Antigua, which did not have satellite earth stations, a transportable dish shipped from the USA was utilised. This feed was then transmitted to the Intelsat V satellite, 39,000 miles up in the stratosphere, then down to the British Telecom Tower in London and on to Sky TV studios. From the latter, the signal was redirected to the Astra satellite for further retransmission to Sky subscribers in the UK and Europe. Caribbean television stations and those individuals in the Caribbean and North America who had their own satellite dishes received their feed from a separate American satellite.

The first ball ever televised live around the world from the West Indies was bowled by Gladstone Small to his fellow Barbadian Gordon Greenidge in the First ODI between England and the West Indies at the Queen’s Park Oval in Trinidad on Valentine’s Day, 1990. The match was recorded as a ‘No Decision’ as rain stopped play. Scores: West Indies – 208 for 8 off 50 overs, R Richardson, 51. England 26 for 1, off 13 overs. The Second ODI was abandoned due to the weather (which had a severe impact on the first half of the tour) after 5.5 overs with the West Indies 13 without loss. Franses later admitted, “To tell the truth, I was scared stiff when we started that first day in Trinidad.” Live Cricket televised from the West Indies had become a reality.

The tour then shifted to Jamaica, where, at Sabina Park, England stunned the West Indies by nine wickets to win the First Test of the 1990 Cable and Wireless Test Series despite the loss of the entire fourth day’s play, following heavy rain on the rest day. England required only one session on the final day given their disciplined commitment and careful planning for the upset, their first victory over the West Indies in 30 Test matches since their last in 1974 at the Queen’s Park Oval and their first at Sabina Park since 1954. Dates: February, 24, 25, 26, [28], March 1. Scores: West Indies 164, A Fraser 5 for 28, & 240, C Best, 64, G Small 4 for 58, D Malcolm 4 for 77. England, 364, A Lamb, 132, R Smith, 57, & 41 for 1. Pain for the West Indian fans, euphoria for Sky Television.

Two days later, with the West Indies requiring three runs to win off the last ball of the Third ODI at Sabina Park, fast bowler Ian Bishop struck a boundary off Angus Fraser to ignite an invasion of the ground by the 18,000-strong, partisan home crowd. Scores: England 214 for 8 off 50 overs, A Lamb, 66. West Indies 216 for 7 off 50 overs. West Indies won by 3 wickets. Joy for the West Indies, work for TWI and SKY.

The television crew then faced the first of two major challenges. The Third ODI took place on 3rd March, and the Fourth ODI was scheduled for Bourda, Georgetown, Guyana on 7th March. Then there was literally only one day, 11th April, between the end of the Fourth Test at Kensington Oval, Barbados, and the start of the Fifth at the Antigua Recreation Ground. Franses recounted, “We just had to get moving immediately the last ball was bowled, taking down everything, packing and getting it to the various airports for flights either the same night or early next morning. it was quite an undertaking and the crew worked magnificently.”

Guyana was one of the last countries in the world to get television, in fact, it wasn’t until Vieira Communications Television (VCT) began telecasts in 1982 that the general population had access to television. Thus, when the TWI/SKY crew were setting up and began encountering problems they sought the assistance of local personnel, there were not too many experienced technicians who could go to their aid.

Hoppie

Harold “Hoppie” Hopkinson sat in his den in the bottom flat of his security office. It was mid-October, Hoppie’s feet were propped up on his desk, as he simultaneously tried to connect on an overseas call, fiddle with a gadget and answer questions on the 1990 breakthrough of live cricket broadcasts from Guyana. The room is filled with all manner of equipment: car parts, racing tyres, electronic devices. Hoppie, whose background is electronics and avionics, is a tools guy, always up to date on the latest developments. We have known each other for close to 50 years. My earliest memories of him being seeing him with his omnipresent knapsack on his back bugling with books, and/or, a chess set tucked under one arm. I recall seeing him scurrying around Bourda during the first match ever broadcast from there, the Fourth ODI. Scores: England 188 for 8, off 48 overs. West Indies 191 for 4, off 45.2 overs, C Best 100, D Haynes, 50. West Indies won by six wickets.

Asked about this, Hoppie related: “At the time, I was the Engineer at the Guyana Public Communications Agency (GPSA), formerly known as the Film Centre, and my boss, Enrico Woolford, the General Manager called me and asked if I could go over and assist the television crew at Bourda as they were encountering some problems.

“I had set up the arrangements for the televised broadcast of the Patrick Forde/Salvador Sanchez World [Featherweight] Title boxing bout [13th September, 1980] at the National Park. We had to run a coaxial cable from the earth station on Carifesta Avenue, which I had to inflate with a bicycle pump. The crowd at the park never realised that there was a five-second delay between the video and the sound, which I had to rig up with a temporary contraption.”

Turning back to the cricket broadcast, he said: “There are three major formats for analog television – NTSC, PAL and SECAM. Guyana is in South America which uses PAL and SECAM, the Caribbean uses NTSC. They were under the impression we were all using the same system. Also, they didn’t appreciate that we didn’t have a reliable source of constant electricity, an absolute necessity for live satellite broadcasting.

“You see,” Hoppie put his phone down and demonstrated with his hands, “the Earth and the receiving satellite are both moving, and the transmitting dish, which was located over at the GFC {Georgetown Football Club, next door to Bourda), near the front gate, was not locked into the satellite, but rather was continuously tracking it. Thus, if there was a blackout, we would lose the satellite and when power was restored we would have had to go look for it.

“You know I have a short fuse. I had an argument with Tony Baldwin Lewis, the Operations Manager, and I was actually leaving, before we sat down and thrashed it out. You have got to make people understand Guyana is not like anywhere else. I had to bring ‘Betsy’ over. Yes, that’s what we called her, the ‘Betsy’, the generator over at GPCA. If we lost power for a few seconds the broadcast would have been cut off.

“The commentators were using one of the radio commentary booths at Regent Road. [Radio Demerara and the Guyana Broadcasting Service (GBS), the radio stations at the time, both had booths]. The control centre with all the television panels, the playback monitors, the support crew and Simon Wheeler, the live feed director, were housed in two containers slung across the Regent Road trench behind the commentary booths. They were sweat boxes, all the men were stripped down to their waist, no one wore a shirt.”

The initial broadcast went smoothly.

“I worked with them until 2002,” he reminisced. “I basically grew to handle all the arrangements for the entire Guyana leg of the tour. Making all the arrangements; from transporting all the equipment from and to the airport, overseeing the security for the entire time. We had to have round-the-clock security at the ground, even before the stuff arrived at the ground. We are talking about millions of dollars in equipment, the catering for television crew and the support staff.

“We worked long hours.We were usually there by 7.30/8 and would leave the ground by 6:30/7. The TWI crew were highly professional, everyone knew what they had to do. When the match was over, it was a clockwork operation. Each single piece of equipment went into a specific box which had attached an inventory as thick as a telephone book. Everyone worked. They were no slackers. When we heard ‘It’s a wrap’, we knew we were finished and ready for the next leg. I also worked with them in Trinidad, Barbados and Antigua.”

Hoppie laughed when I suggested he was the resident MacGyver.

Torrential rain left several areas of Bourda waterlogged and the Second Test match scheduled for March, 10, 11,12, 14, & 15 was cancelled after the first three days, and two ODIs were scheduled for the final two days. Only one was played on 15th March. Scores: England 166 for 9, off 49 overs. West Indies 167 for 3 wickets, off 40.2 overs. G Greenidge 77, C Lambert, 48. West Indies won by 7 wickets.

The tour then wound its way back to Trinidad for the Third Test, before shifting to the Kensington Oval for the Fourth, and concluding with the Fifth Test in Antigua. The West Indies won the latter two Tests to take the series 2 -1. They also won the five-match ODI series 3 – 0, to take the Buckle Trophy.

The commentary team for the television broadcasts comprised former England captains Tony Greig and Tony Lewis, who were seasoned campaigners with Australia’s Channel Nine, and England’s BBC, respectively; former England opening batsman, Geoffrey Boycott; former West Indies fast bowler Michael Holding and West Indian journalist and broadcaster, Tony Cozier. When Holding departed for New Zealand for a series of benefit matches during the Third Test at the Queen’s Park Oval, Roger Harper, still an active player, fulfilled the duties.

Postscript

Mixed reviews greeted the live telecasts. Sky’s David Hill observed, “Now that Sky and TWI have proved that this is doable … every television network will have to ask itself the question when their team tours the West Indies, can we afford not to televise the series? Simple logic and an understanding of supply and demand would indicate the price of rights would escalate.”

CBU President Terry Holder noted that the prohibitive cost to CBU stations to accommodate satellite time for the series coverage was US$215,000. CBU stations took all-day coverage of the ODIs, but only on weekends and public holidays for the Tests, and the final session – post tea – on weekdays. There was no live transmission where the matches were played.

West Indies Captain Viv Richards was upset with the commentary. In a radio interview, he said, “There are lots of people who have listened to cricket who are feeling pretty hurt about this, that here we are in the Caribbean, having these guys [Boycott and Greig] talking a lot of rubbish over our airwaves.”

West Indies Players’ Association Secretary Jeffrey Dujon petitioned the WICBC for a share in the rights fees and drew a blank cheque. Dujon asserted that the deal had been secured because of the team’s consistent performances in recent times.

On 3rd February, 1991 it was announced that the 1991 Cable and Wireless Test Series between the West Indies and Australia was going to be broadcast on live television. Initial negotiations between IMG and Australia’s Channel Nine television network had gone nowhere, with Australia’s then current recession and the time difference – live coverage of the Tests would be between 1 am and 9 am – being cited as the reasons. TWI provided the operational support, with Channel Nine supplying two producers and two commentators, former Australian captains Richie Benaud and Ian Chappell, with technical support from CBU stations.

The deal was reportedly worth the same to the WICBC as paid by Sky Television the previous year, US$250,000. Live cricket television broadcasts from the Caribbean were a reality.