If one were to scrutinize the photographs of all the West Indies cricket teams from the beginning of the 1980s and to the culmination of the 1990s, one would notice the consistent presence of one man; a stockily built Caucasian, standing 5’ 8” (everyone appears miniature next to those giant fast bowlers of yore), always neatly attired with a tie and West Indian blazer or suit, standing at either the extreme left or extreme right of the second row of the group. No, he was neither the manager, the assistant manager, nor the scorer. Dennis Waight, the trainer/physiotherapist, was an important cog in the West Indies era of unprecedented success.

Origins

Bank Holiday Monday, 5th August, 2002, King City Ground (just north of Toronto), Ontario. The West Indies A Team, on the way home after a tour of England, is engaged in a One Day game versus Canada. Joel Garner, the team’s manager, conversationalist extraordinaire, is explaining the origins of the association of Dennis ‘Sluggo’ Waight and West Indies cricket.

“We had just lost a night match in Sydney. Australia had bowled us for 66. [Research indicates it was 27th December, 1978; West Indies 66 off 33.4 overs, Lawrence Rowe, 25. Australia, 69 for 4, off 18.3 overs, David Hookes 33*.] After the match, Kerry Packer [World Series Cricket (WSC) founder] stormed into the dressing room, and read the riot act to us in three minutes. At the top of his voice, in very colourful language, he declared that he was paying us big money but he wasn’t paying us for the kind of performance he had just seen.

“‘There are planes leaving for Los Angeles everyday and I have no problem with paying the ‘#$%*&’ lot of you off as per your contracts, and sending you on your way, and replacing you with another bunch of players. Tell me what you are lacking by tomorrow, and I’ll get it for you, but I’m not paying for this crap.’”

Garner chuckled, “Well, we had a team meeting, and we came to the conclusion that we needed to up our fitness levels. We suggested there was a need for a full time trainer. Enter Dennis Waight.”

………..

The Australian physiotherapist David McAlain assigned to the WSC West Indies squad approached Waight, a former Australian Rugby League professional, whose playing days had come to an end following a knee injury suffered during a game. Waight had stayed on, working as a trainer with the New South Wales rugby league and rugby union teams. Initially offered the job as the trainer for the WSC World XI, Waight opted for the WSC West Indies XI whom he had seen in action during the debacle of the 5-1 thrashing meted out by Australians during the 1975/76 tour. He was puzzled how a team of such talent could suffer such a lopsided defeat.

When Waight arrived on the scene, there was no fixed or regular exercise programme in place in West Indies cricket, and players were left to their own devices to attain and maintain their own standards of conditioning. After informing Captain Clive Lloyd that the team’s average standard of fitness was nowhere near what was required by international sportsmen, Waight was given carte blanche to create a programme. The naturally gregarious trainer set about simultaneously developing his plan of action and a good working relationship with the cricketers, whilst invoking the intensity and mental toughness of his former discipline. He was a hard and demanding task master, and his charges duly responded to the challenges set. As the fitness level of WSC West Indies squad ascended, their injuries diminished and there was an improvement in their already high standard of play.

When WSC closed after the 1978/79 season, Lloyd persuaded the West Indies Cricket Board of Control to retain the services of Waight. Previously, the Board had utilised the services of a masseur or physiotherapist on an ad hoc basis. Manny Alves, a Jamaican, had accompanied Frank Worrell’s team to Australia in 1960-61, while Hubert Cromarty, a Guyanese, went with Gary Sobers’ 1968-69 team Down Under. On tours of England, it was customary to retain the services of an Englishman.

On Saturday, 18th March, 1995, during the Fifth ODI between Australia and the West Indies at Bourda, Georgetown, former West Indies (1978-82) opening batsman Faoud Bacchus, introduced this writer to Waight. Sitting in the Players’ enclosure, listening to Waight outline his career with the West Indies, whilst following the game one caught a rare glimpse at him at work.

An Australian batsman drove the ball past the bowler for what looked like a certain boundary. Jimmy Adams, the fielder on the deep mid-wicket fence had other ideas as he raced like a hare around the boundary line, intent on intercepting the ball before it crashed into the boundary board. Dennis, as the players all referred to him, aborted his sentence, focused sharply on the action as Adams closed in on the ball. He stuck his foot out at the last second, soccer style, just missed, stumbled over the boundary board, and collided with the South Stand B fence.

Dennis sprung to his feet, staring intently, as Adams clutched his knee in pain. Dennis whirled his arms in a mass of signals, as Adams, the selfless team player, hobbled back to his position, ignoring the windmilling gestures. Over the ensuing two to three minutes, the trainer silently focused on Adams’ every move, before resuming the conversation, whilst making a mental note to examine Adams’ potential injury at the first opportunity.

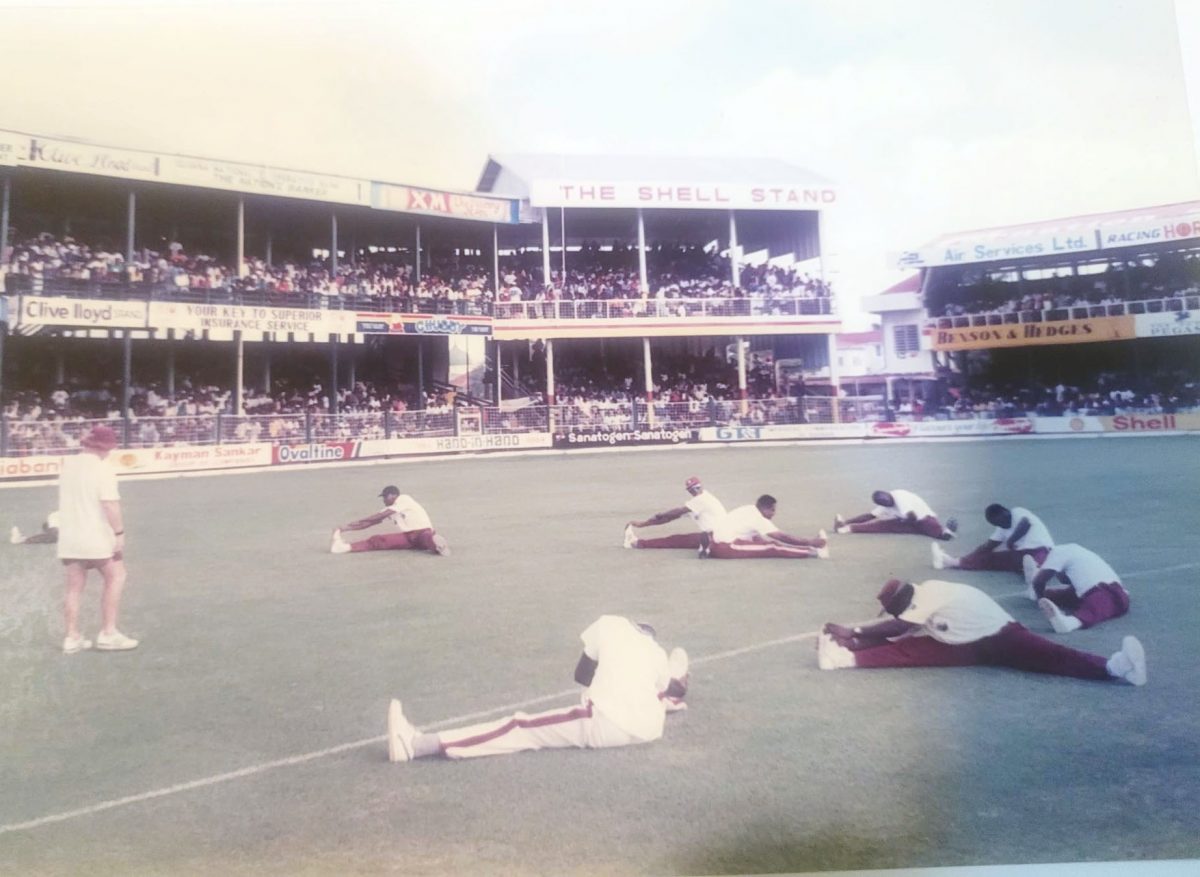

A firm believer in long static stretching, he instituted a sequence of exercises to improve the flexibility of the entire squad, along with sets designed to meet the needs of specific individuals. Coupled with stretching, sets of 300 to 400 sit ups and long runs on the road to improve endurance and stamina were introduced. His goal was for every player to achieve an amalgam of endurance, strength and flexibility to reduce the chances of injury.

His modus operandi was ‘prevention is better than cure.’ Back in the day, early arrivals for Test matches and ODIs, witnessed the entire West Indies squad being put through their warm up paces for over an hour under the watchful eye and stewardship of Waight, decked out in his signature outfit of, t-shirt or golf shirt, shorts, socks and sneakers, performing all the exercises, never asking his players to do what he couldn’t execute. Each session began with a series of stretching exercises which took half an hour to complete, followed by sets of calisthenics and sprints.

Waight eventually morphed into the additional role of physiotherapist, having increased his knowledge in that area with a number of courses on his own time. His approach to the treatment of injuries was a blend of Western (modern medicine) and Eastern (ancient practices) culture. Keeping the stable of fast bowlers in good shape continuously was among his many difficult challenges, apart from getting everyone to appreciate the importance of being at peak fitness. He noted that the sustained pounding the thoroughbreds put on their legs at the point of delivery required him to be constantly measuring their legs and building up their cricket boots to maintain equal leg length and avoid pressuring the spine.

Extending the playing careers of most of the players under his charge was among his most important achievements (Lloyd was still playing Test cricket at the age of 40). The sharp increase in the number of ODIs – “which,” Waight said, “bring out the slightest ‘niggle’ in a player that he can otherwise coast through an entire Test match with” – and constant travel added more wear and tear to the players.

Waight missed only two official West Indies tours during his years of service to WI cricket. The first was the second leg of his inaugural series, the 1979–80 Tour of Australia and New Zealand, since he was still contracted to a Rugby League Club in Sydney. The second was the 1988 Tour of England. He was recovering from spinal cord surgery sustained during the 1987/88 World Cup and Tour of India. He was returning to his hotel room one day, when a loose air-conditioning unit fell on the neck of his ursine body. Momentarily stunned, he completed the tour and returned to his Sydney base in Australia. A few weeks later he experienced slight tightness in his chest and numbness in his lower arms. A thorough medical examination revealed that he had a badly severed spinal cord and required emergency surgery. His thick neck muscles had saved him from becoming a quadriplegic. Waight spent nine months lying on his back to recuperate. He did, but was no longer able to run. Gone were the days of three and four hour runs and his signature runs between the team’s hotel and the Test ground, often beating the team coach, stuck in traffic, back to the hotel. He resorted to extended swimming sessions and long brisk walks.

The WICBC let go of Waight after the 1999–2000 tour of New Zealand, as an entire new management team was assembled for the 2000 home series versus Zimbabwe. Little did we know that an era had come to an end. Dennis Waight deserves heartfelt gratitude for his yeoman service to West Indies Cricket. He was worth his weight in gold to the team.

Post West Indies career notes

In July, 2002, Waight signed an eight-month contract to work with the Pakistan cricket team until the completion of the 2003 World Cup.

WICBC tribute

Following the historic victory over Australia – the highest successful fourth inning run chase – in the Fourth Test match in May, 2003, at the Antigua Recreation Ground, the West Indies Cricket Board paid tribute to Waight, acknowledging the role he had played in building the West Indies into a world power and for his length of service.

Holding on Waight

In his second book, No Holding Back (2010), Michael Holding (with Edward Hawkins) dedicated the entire sixth chapter titled ‘Dennis’ to Waight. In six-plus pages Holding delved into the depth of Dennis’s relationship with the team, especially with Lloyd, and sharing in prize money and their failures. Waight’s innovative approach to using old bicycle tubes for strengthening exercises on the road since most hotels in those days didn’t have gyms was duly noted. He stated that other cricket teams were not working on aspects of fitness to their level and recalled doing Waight’s signature five-mile run – no exceptions – through villages in Pakistan and small towns in Australia. The fast bowler also recalled Dennis’s strength. “He had the constitution of an ox,” Holding wrote. His fondness for a night out and the exceptional ability to rise the next morning none the worse for the wear to lead the team on its daily run, was evidence of that.

The former fast bowler summed up Waight’s influence in the following words, “There is no doubt in my mind that the work done by Dennis was the catalyst for West Indies’ period of dominance that would follow World Series. Sure, we had some great talent in the team, but the level of fitness we achieved helped us to remain on the park and maintain the high level of performance over a longer period.”

Lingering question

Why was Dennis Waight let go when he still had so much to offer West Indies cricket? Rumours abounded for years. On 1st March 2015, Tony Cozier, writing in his weekly Sunday column, ‘Cozier on Sunday’ (which was syndicated throughout the Caribbean), under the caption “Improved fitness could help restore pride to West Indies cricket,” provided the answer:

“He [Waight] was in the role for 23 years. The end was signalled on the 1999-2000 [actually 1998-1999] tour of South Africa. Those who had come up under him had retired and their successors deemed his methods too demanding.

“I realized the problem when I returned to the team’s hotel in East London one morning and found Waight in the bar when, at that time, he was usually out conducting his training sessions. The manager, Clive Lloyd, told him captain Brian Lara and vice-captain Carl Hooper had approached him to ask that Waight ease up on his workouts; Waight duly obliged.

“‘It just means I can have a couple of beers in the morning now,’ he told me.”

The West Indies were swept 5-0 in a Test Series in the 1998-1999 tour of South Africa.

Final thoughts from Waight on the modern game from an online interview with Cricket Web.net in October, 2017.

CW: “In those days, you had a coach, captain, physio as part of the management team. However, today, we have a slew of support staff ranging from a performance analyst to a masseuse. As an old timer, what are your thoughts on that?”

Waight: “I sometimes think it’s a little bit of an overkill. However, you must remember when I was around, it was just a sport and now it’s a business and it’s big money. Looking at some teams, there are probably eight guys doing what I used to cover in those days. I was fortunate that I ended up with a team that went undefeated for 16 years. There was the manager, myself and that was it. We had a tour of India in 1983 after the World Cup. I think it was six Tests, six One-Day games [Five ODIs and one benefit match], ten [six] three-day games and three [one] two-day games. We had 15 [16] players in the squad. The whole tour, no one got injured or sent back, we won the [ODI] series [5 – 0] after getting beaten in the World Cup. We dominated that [Test] series and destroyed them [3 – 0].

“There are a lot of reasons for what they are doing now, but I still think it’s overkill and I feel that the players are pampered a fraction too much.”