Howl, howl, howl! O you are men of stones.

Howl, howl, howl! O you are men of stones.

Had I your tongues and eyes, I’d use them so

That heaven’s vault should crack.

Shakespeare, King Lear

Now is the winter of our discontent

Made glorious summer by this sun of York

And all the clouds that lour’d upon our house

In the deep bosom of the ocean buried.

Shakespeare, King Richard The Third

Michael Gilkes’s The Last of the Redmen (2006) by is one of Guyana’s foremost dramas, occupying a place of significance among the best of Guyanese theatre and as a major work of Guyanese literature. It holds the distinction of being the winner of the Guyana Prize for Literature 2006 and was first produced in that same year by GEMS Theatre Productions, directed by Gilkes who also played the role of RAF Redman in what was then a one-man play.

It tells the story of an old man with an illustrious, if elusive, past living out his last days in an old people’s home. It resonates with echoes of the history of Georgetown in its rather faded glory, of a disappearing middle-class taking with it a society and a culture with strength of character, honour, colonial and post-colonial at the same time, and a rich heritage of the arts. The work has the feel of the passing of an age and the loss of values no longer recognised by a new generation contemporary society

Gilkes puns on the name “Redman”, which can easily be read as the decline of the “red men” in West Indian parlance – a middle class of coloured gentry once strong in old Georgetown but now limited in number and cultural presence. The main character’s name is “RAF Redman”, clearly a deliberate ring of the initials. He belongs to a generation when it was one of the great undertakings and experiences of men in the British colonies to serve in the Royal Air Force in World War II. The play is an elegy not only for Redman, but for the Guyanese middle class, the people of light complexion, the strong culture of old Georgetown, a lament for the world and for humanity. Where the last is concerned, much is drawn from Shakespeare’s great tragedy King Lear. There are many quotations and a lasting tragic sense in Gilkes’ play and the consciousness of his main character.

This play, furthermore, has a strong base in history and autobiography since it fictionalised Gilkes’ own relations with the Taitt family, owners of Woodbine House, popularly known as Taitt House, a coloured, middle class household with a love for the arts. Members of the Taitt family included dancer and poet Helen Taitt and actor Clairmont Taitt. The house served as theatre, and cultural meeting place for several artists including Gilkes, Stanley Greaves, Philip Moore. There were performances, classical music, concerts, ballet, exhibitions, musicals, including the premiere of one of the famous plays in Guyanese theatre, the dance drama Stabroek Fantasy written and directed by Helen Taitt. It was therefore fitting that the premiere of The Last of the Redmen in 2006 was staged in the same famous Ballet Room of Woodbine House now converted into the Cara Lodge Hotel.

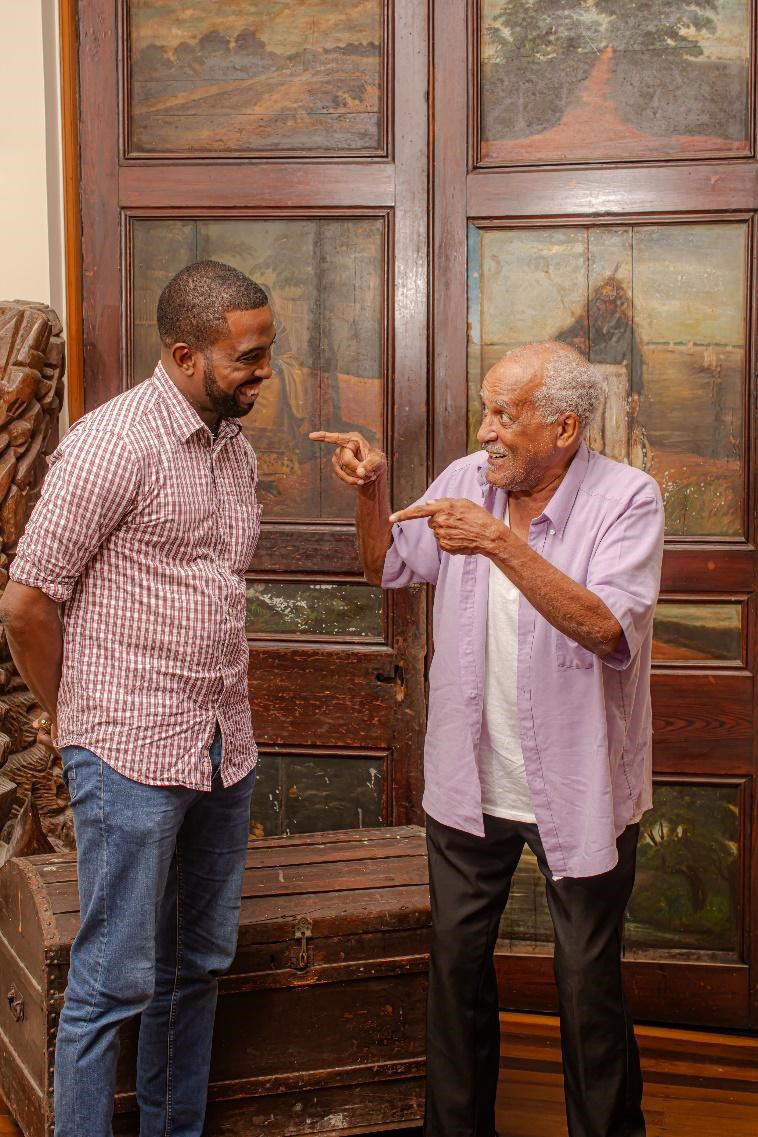

A recent revision was performed at the National Cultural Centre (November 3 – 4) and at the Theatre Guild Playhouse (November 18 – 19). It brought together a team including some leading technicians in the Caribbean and was produced by Gem Madhoo-Nascimento for Gems Theatre Productions in collaboration with Prime Time Productions. The director was Henry Muttoo, assisted by Madhoo-Nascimento, and Ron Robinson played Redman, supported by Mark Luke-Edwards as the Reporter. Madhoo-Nascimento is an accomplished and acclaimed theatre producer, Robinson has had a lengthy career as an outstanding and acclaimed actor and director, while Muttoo is an outstanding director and designer among the most revered in the West Indies.

Muttoo served as more than director, since at the request of Gilkes many years ago, he dramaturged the play, revising it to what it is now – no longer a one-man play. Invisible characters from the original version now appear on stage: the Reporter and the children. The latter were played by Latiefa Agard, David Hackett, Stephon Romain and Akeila David. As performed in this dispensation it was a much leaner, neater play, less rambling and quite easy to follow.

The 2023 production of The Last of the Redmen came into being as a part of the initiative of Minister of Culture Charles Ramson Jnr, who proposed that all the plays that won the Guyana Prize be performed with production costs borne by the Department of Culture while ticket sales are retained by the producers. This was the third play under this scheme. The first was Sauda by Mosa Telford, directed by Ayanna Waddell and performed by the National Drama Company (NDC) as part of the Guyana Prize Literary Festival in February, and the second was Makantali by Harold Bascom directed by Godfrey Naughton. Performances of The Last of the Redmen were further embellished by being staged under the patronage of Prime Minister Mark Phillips.

In the play, RAF Redman, who had a career as a professional actor in England, announces that he is writing a play described as “a dramatic performance by a lost, living actor conjuring images from the dead past”. He invites the press to interview him and a young up-and-coming reporter is sent. Redman is consistently preoccupied with the lost value systems of a dying age, a fading culture of the arts and very much with images of his past life, including the tragic loss of his wife and daughter. Redman often sees himself as King Lear. The strongest emotion is one filled with nostalgia and Redman relives moment after moment.

Robinson displayed full understanding of the character, carrying the audience effortlessly but always convincingly through the stages of nostalgia, moralising and upbraiding the youth of the day, represented by the reporter, for their lack of understanding and appreciation of discipline and values.

One understood Redman because of a full character creation by the playwright, fortified by dramaturg. But one saw Redman because of an exceptional exhibition of character study and representation by Robinson in one of the best recitals of excellent acting seen on a Guyanese stage. It was a crowning demonstration at this point in his long career exhibiting a master of the craft in a major play with an important and demanding role. That was a memorable 90 minutes on stage that delighted audiences. One wondered why both the director and the producer in the programme notes referred to a “swan song” and “final show”. If Robinson has announced his retirement from the stage, please excuse me if I didn’t hear it. But pardon me, what we saw on stage in this play was something momentous to be valued and celebrated in the present, not to be alluded to as something of a last gasp.

Robinson was very effectively supported by the unassuming performance of Luke-Edwards, an NDC member, whose visiting interviewer was always sensitive, handling his subject as carefully and attentively as a tray of eggs, fragile but precious, to be protected for the value there to be reaped. The acting was studied, treating the old man with deference and with unending patience, but always conscious it seemed, that he was sent to represent his newspaper and was doing a job. This was an outstanding, measured performance in a supporting role.

His appearance on stage was the work of the director Muttoo who carried out a seamless operation making changes that improved the daunting play. It was not easy to see the changes from old script to new. That work was similar in the case of the children who fitted in neatly with efficient playing by Agard, Hackett, Romain and David who did not have much to do but carried it out effectively.

The set was first class, fixed out of sound knowledge of the stage with a greater emphasis on utility, using props and embellishment to set the scene both physically and symbolically. Nizam Bacchus’ lighting design was always understandable, but at times a bit ineffectual. Moments were highlighted in colour, understandably in flashes of the past, but there was some untidiness in its ability to assist the flow of the play.

Where this flow was concerned, questions remained. For the majority of the play Redman showed much spark and less signs of mental deterioration. He was often very witty, and his lines did not suggest the sudden collapse at the end into Lear-like madness and a rapid descent towards his demise. The script appeared there to have experienced a touch of deus ex machina.

Yet this is a play quite powerful in its symbols and imagery of death, collapse, pathology and a tragic, powdery past. Redman’s father was a pathologist and kept all his records in a trunk, now symbolically used by Redman to store things from the past which seem part of a post-mortem examination that he constantly carries out. He climbs into the same trunk in his last moment as if he, too, was the subject of the decline, the pathological factors that he dissects throughout the play.

This ties in with several cases of intertextual engagement by Gilkes who made use of echoes from other literary and dramatic works. These included Derek Walcott’s Remembrance, Shakespeare’s Richard III, and Samuel Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape. But the major work on which the play rests is Shakespeare’s Lear. Redman played Lear as an actor but the play haunts him as it haunts his life, particularly in the tragic loss of his daughter, paralleled to Lear’s loss of his daughter Princess Cordelia and subsequent decline into madness, a reflection of the insane errors he made as a king and a father. Those echoes make Redmen and makes its main character into a Caribbean King Lear.

The reporter visiting to interview the old man ties in with Walcott’s Remembrance, especially in the reflections of the issues of culture and class. The references lend the play some strength as a literary work, whose meaning is fortified by the comparisons and textual issues. As a work of theatre The Last of the Redmen was fully appreciated by audiences. In particular, it made an impact especially driven by the memorable performance of Robinson for which this play will be marked.