“If there are ten doors you could go through and only one you must go through, a kind God closes the other nine.” Such were the words that returned to me as I read the acceptance speech of Bernadette Indira Persaud delivered on the occasion of being conferred with an Honorary Doctorate for Excellence in Arts from the University of Guyana on November 11, 2023. Born in Bush Lot, Berbice and coming of age at Mackenzie High School and later St Joseph High School in Georgetown, the path Persaud has journeyed could not have been anticipated. As a consequence, the door through which she did her life’s travel could not have been predicted.

“If there are ten doors you could go through and only one you must go through, a kind God closes the other nine.” Such were the words that returned to me as I read the acceptance speech of Bernadette Indira Persaud delivered on the occasion of being conferred with an Honorary Doctorate for Excellence in Arts from the University of Guyana on November 11, 2023. Born in Bush Lot, Berbice and coming of age at Mackenzie High School and later St Joseph High School in Georgetown, the path Persaud has journeyed could not have been anticipated. As a consequence, the door through which she did her life’s travel could not have been predicted.

After years teaching English Language, Literature, and Art at the secondary level, Persaud found the door she had stepped through closing in on her. “The year,” she writes “was 1980.” After teaching first at Charlestown Secondary School from 1967 to 1977 and then at St Rose’s High School from 1977, Persaud was dismissed from her post. She writes, “paraphrasing the words of the distinguished Guyanese poet Martin Carter:

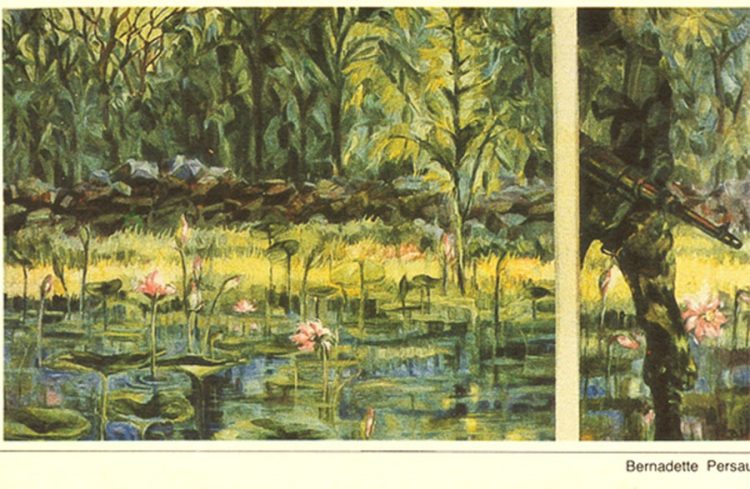

Oil on Canvas Paper, 1983 (Photo source: Scan from a newspaper, Archives of the Artist)

“It [was] the season of oppression, dark

metal, and tears.

It [was] the festival of guns, the carnival of

misery.

Everywhere the faces of men [were] strained

and anxious.”

She continues, “It was a year that was marked by political and economic instability. It was the year of the 1980 Constitution and the year of executive presidency. It was the year of pickets and protests. It was the year the schools became part of the rising militancy against a malignant administration.”

Persaud’s words and actions in the environs of the government school had been deemed problematic. “How could I sit passively, in the classroom/artroom, working out the proportions of bottle and jars, tracing the subtleties of linear and aerial perspectives, while outside the lines and queues of suffering were lengthening?” she asks. Persaud’s inability to be silent and apathetic was met with dismissal. On June 24, 1980, less than two weeks after a great man of the soil had been assassinated for his words, she was instructed to report to Port Kaituma Secondary School. Other teachers at other schools were issued with similar directives. Thus, in an independent Guyana, the tactics of the former colonial administrators to silence and avert dissension were being repeated. But unlike those who must have followed, Persaud was unable to do so even if remotely inclined due to circumstances beyond her control. Persaud’s failure to do as instructed led to her dismissal from her job and the end of her income during trying economic times. She writes, “On this day life’s predictable charter changed significantly. I had lost the right to work and seemingly the right to live and the right to support my family. I had lost the right to a pension and the right ‘to sleep perchance to dream’” (William Shakespeare: Hamlet Act III Scene I).

Persaud continues, “After years of teaching, not to be going through the familiar routines of ‘chalk-and-talk’, endless marking, the daily challenges in the classroom, certainly left a vacuum in my life. When several attempts to find a job failed, I realized that I had joined the ranks of those who did not have the right to work.”

Oftentimes the doors through which we must travel, we are being prepared for when we least expect it. Hours spent drawing as a child fueled interest in art as a form of visual discourse (even provocation) that allowed Persaud to take advantage of opportunities to develop and hone skills when they presented themselves. As a student at St Joseph High, she studied the canvases of Guyanese artist Dudley Charles, and her thinking about art was made less quotidian through conversation with the venerable Philip Moore. As a teacher at Charlestown Secondary, she eventually crossed paths with Denis Williams who encouraged her to join his newly formed E R Burrowes School of Art. (By then she was already a graduate of the recently established University of Guyana having majored in English and minored in History.) Meanwhile, as a teacher at Charlestown and St Rose’s High she writes, “I had discovered the canvases of Monet and the lush impressionist strategies of the mid-19th Century radicals, the philosophy of the Upanishads and the psychology of Jung. I had discovered the language and lyricism of Robert Frost – poems that would haunt and influence me in later years, the metaphysics of the Bengali Nobel laureate Rabindranauth Tagore and the rebellious fire of Guyana’s post-colonial master Martin Carter […]”

In 1981/82 Persaud accepted an invitation from her close friend and former teaching colleague Rosamund Addo to assist with a holiday project for children. In the Botanic Gardens, Addo recited poetry from Martin Carter and Wilson Harris to the children and Persaud guided their sketching. The project was what Persaud needed. Her time spent in the relative tranquility of the gardens with the children, inspired her to return after the project was finished. She writes, “The images of the lotus in the sunlight, whispering trees, falling leaves, birds taking wing, the bird caught by an alligator and the armed soldier at the gate were so compelling that not long after the children departed, I began my own life-project-painting, series after series: ‘Fragments of Life,’ ‘Bird Island’, ‘the Botani-cal Gardens’, ‘A Gentleman in the Gardens,’ ‘the Lotus of Time’… I had found myself.”

Today, many should have gratitude that Persaud found herself. I am thankful she found the door through which she must travel. Through her ‘Gentleman in the Gardens’ canvases which hung on the walls of the eatery in the Guyana Stores Limited, I learned of a Guyana that haunted mothers and fathers into silence and why ‘O Beautiful Guyana, O my lovely native land’ was left behind by so many – a stop from the past as they grabbed on to a new, uncertain but less ominous future. These early canvases by Persaud explained a Guyana spoken about in hushed tones, especially around children who lived her reality in youthful innocence and in as much naiveté as one’s parents’ economic circumstances afforded.

As Persaud wrote of the early beginnings, “For me, the gardens with its primal beauty and the man-with the gun, became the dominant symbols of life: the serpent in Eden, a dream of innocence and beauty gone awry. At another level, the gardens – the central metaphor of my early paintings – became the point of departure for exploring themes of transience, beauty, mortality, political oppression and cultural identity.”

(To be continued.)

Akima McPherson is an artist, art historian, and educator.