By Gemma Robinson

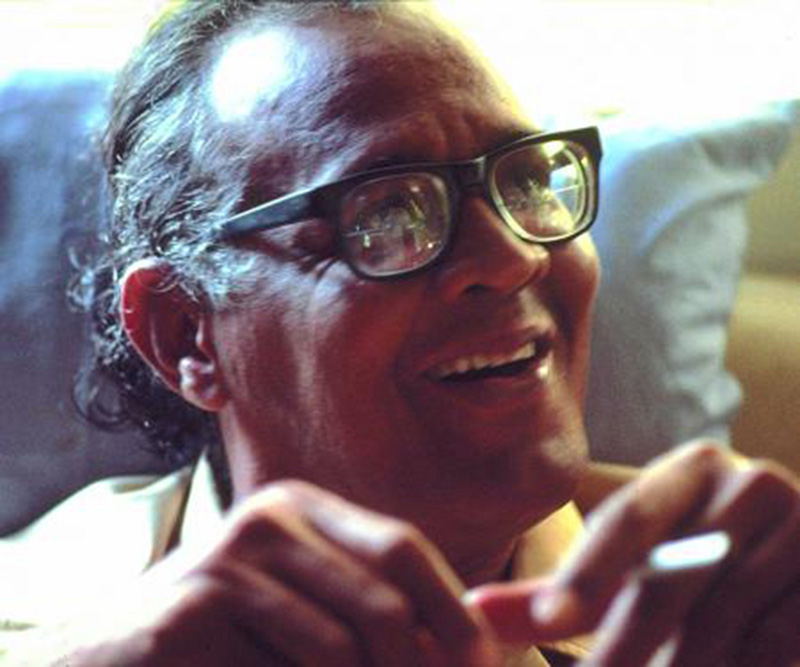

Moray House Trust in Georgetown held its annual Martin Carter memorial event this week. Since 2011 the Trust has been reminding audiences of the power of Carter’s poetry. Standing at the corner of Camp and Quamina streets, the building was the family home of David de Caires, the founding editor of Stabroek News. Now it is the home of the non-profit organisation with the motto ‘Culture Matters’. For the last few years, and especially during Covid-19 lockdowns, Moray House online events connected people locally and globally to read and listen to Carter’s work. Yesterday saw the return of an in-person event, organised by Isabelle de Caires, and Carter’s 1961 sequence of poems, Conversations, was in the spotlight.

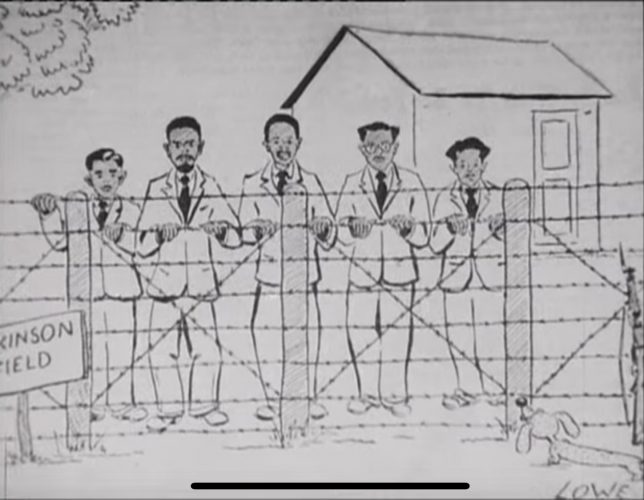

As we focus on Carter and his interests in conversation, we should also remember that exactly 70 years ago, Martin Carter was being held indefinitely at Atkinson Field during the 1953 emergency. Christmas was coming. He was 26, married to Phyllis, with a young baby, Keith. The PPP government had been removed, British troops occupied the country, public meetings had been banned, and Carter’s work had been seized in Georgetown. Eusi Kwayana remembers that the detainees were confined for 24 hours a day, with no access to the outdoors or visitors. But they had each other for company and Rory Westmaas remembers Carter sometimes sharing the poems that he was writing. Carter’s poems kept reaching out, making connections, having conversations on the page that he couldn’t have in person. In ‘Letter 2’ he asks about the family. ‘Tell me, the young one, is he creeping now’ and to his wife writes ‘I send a kiss to tell you everything / about today the twentieth in the distance’. In ‘This is the Dark Time My Love’ he asks and replies: ‘Whose boot of steel tramps down the slender grass? / It is the man of death, my love, the strange invader’. Carter’s poetry is a poetry of involvement. It is a poetry attuned to how we share the world with others, especially in moments of crisis.

In Carter’s work there are many times when he uses the vocabulary of communication. Across the full stretch of his work, we find words like voices, speaking, telling, crying, muttering, utterance, declarations, praise and talk. The word ‘conversation’ is a bit different. When the seven untitled poems that make up Conversations were published in Kyk-Over-Al, it was the first time he had used the word in his poetry. And then more strikingly the word doesn’t appear in any of the poems. Over time we can see this as one of Carter’s titling techniques. The word ‘resistance’ doesn’t appear in Poems of Resistance, ‘succession’ doesn’t appear in Poems of Succession, and there are no instances of ‘affinity’ in Poems of Affinity.

But we know that conversation was essential to Carter. Taking action was not the opposite of discussion; the two were tied together. Eusi Kwayana told me that after PPP Executive meetings in the early 1950s their conversations would spill out into the night. He and Carter would cycle to Le Ressouvenir together, talking the whole way, and then Carter would turn around and bike back to Georgetown, while Kwayana carried on to Buxton. Rory Westmaas said Carter didn’t mind fighting for an unwinnable seat in the 1953 elections because he valued the chance to talk with people and understand how they viewed the world. Janet Jagan remembered a prison experience strikingly different from that of the men in the PPP because unlike her they were able to continue talking with their comrades while they were imprisoned. Outside PPP politics, Wilson Harris and Sydney Singh rented a room in Hadfield Street and Carter and others would go there to talk. The Carter house in Anira Street was well-known as a place to come for conversation. In a notebook of the writer, AJ Seymour, poet and editor of Kyk-Over-Al, we can find a short note to himself – just three words: ‘Ring Martin – Hegel’.

We can also get a feel for Carter’s interest in conversation by looking at his open ‘Letter’ published a few years later in New World Fortnightly in 1964. These are challenging, searching words for his contemporaries. He wrote: ‘The almost fanatical preoccupation with hollow issues, the gossip-mongering which passes for conversation, and the inevitable political hysteria, leave little time for the serious examination of ideas. I know that the psychological squalor of everyday life is exhausting. I know that the urgent practical problem of making a living comes first. What I do not know is why only so few revolt, either by word or by deed against such acute spiritual discomfort’.

So conversation is never hollow talk for Carter. It is the serious examination of ideas and a route out of spiritual and material discomfort. And that is why it is so powerful and so painful to read the opening lines of Carter’s poem ‘For Walter Rodney’. He writes: ‘Assassins of conversation / they bury the voice’. Thinking about the etymology of the word ‘conversation’ helps us here. To converse can mean in its Latin form to turn together or turn over in the mind, in medieval French it means to live together, and later in more modern forms of English it becomes talking together. So assassins of conversation do not just destroy speech. They destroy our ways of living together, they destroy our ways of thinking.

A gap of six years separated Conversations from Carter’s last sequence of poems, Poems of Shape and Motion. In the pages of Kyk-Over-al the poems were laid out in a two-page spread, in italics, without titles. Following Carter’s now conventional approach, they appeared without comment. A.J. Seymour added very little in his editorial describing the creative work as ‘viewpoints on the contemporary scene’. Later Carter would cut the second and fifth poems and give titles to the remaining five when they appeared in Poems of Succession.

Between the publication of Poems of Shape and Motion and Conversations Carter had left the PPP, worked as a teacher, become an Information Officer in the British Council’s Georgetown Office and then joined Booker as an Information Officer. If these jobs seemed like they were taking Carter towards a career in communications, and away from the craft of poetry, Conversations proved that poetry and the uses and limits of poetry were always on his mind.

The first poem in Conversations directly tackles the craft of poetry and the poet’s duty to write for a particular readership:

They say I am a poet write for them:

Sometimes I laugh, sometimes I solemnly nod.

[. . .]

A poet cannot write for those who ask

Hardly himself even, except he lies.

Conversation here becomes a series of demands, evasions and refusals. However, the actual conversations become less important than the implications of those conversations for the role of a poet. Carter ends the poem with a difficult and demanding statement: ‘we who want true poems / Must all be born again and die to do so.’ The route to ‘true poems’ takes us to existential questions, and we must all be willing to grapple with the meaning of rebirth and death in order to write and receive them.

Although the poems are not presented as a narrative, they are understandable as a sequence, articulated by one voice, analysing different aspects of disappointment in the present world. In them we find the poet who refuses to write, the poet who dare not keep too silent, speaking ‘quick words’, the poet who is forced into silence, the poet who writes about silence. In the sixth poem Carter offers a Kafkaesque version of conversation, in which the poet and those speaking with him metamorphose. If the ‘prisoners’, ‘politicians’, ‘drunk men’ and ‘murderers’ of the earlier poems seem noisy but not capable of conversation, the articulation of any human words becomes impossible in this new poem:

Groaning in this wilderness of silence

where voices hardly human shout at me

I imitate the most obscure of insects

He ends the poem: I nodded and agreed and listened close. / But when I tried to utter words – I barked!’

In 1954 Carter wrote an article for Thunder titled, ‘An American Oracle’, in which he observes:

‘Every few weeks or so, some official or expert or advisor arrives in British Guiana, and, after spending a few days in the company of assorted reactionaries, completes the visit by making oracular disquisitions either about the Soviet Union or “the communist conspiracy to rule the world,” [. . .] all very much in the manner of the character Shakespeare parodied by crediting with the lines: “I am Sir Oracle, when I open my mouth let no dogs bark”.’

The ‘American Oracle’ was Mr L. E. Norrie, the Public Affairs Officer of the U.S. Information Service who visited Guyana for four days in 1954. The brevity of Norrie’s visit is telling and Carter dissects the hollow noise his ‘oracular disquisition’. Carter’s quotation comes from a longer speech in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice which is dominated by a debate about the appropriateness of speaking: when to do it, when not to, what to say and what to withhold. If Mr Norrie is a foolish ‘Sir Oracle’, who says nothing but professes truth, then Carter’s 1960s interest in The Merchant of Venice helps him to think about the critical power of conversation or silence over speech. The barking voice of the poet in the penultimate poem of Conversations then holds a number of implications: the poet can be protesting, that is his bark can be read as a paradoxically articulate response to the Sir Oracles surrounding him. However, the poet can also be a Sir Oracle – a false prophet – barking but saying nothing.

Throughout Conversations Carter explores the meanings of what he calls ‘this world’. We might say that Carter’s ‘true poems’ are those which face the critical states of the world and remain hopeful for the future. The final short poem, with its explicit flood imagery forms a pronounced expression of this, and the optimism and pessimism that is associated with it. He later titled it ‘So That We Build’:

In a great silence I hear approaching rain:

There is a sound of conflict in the sky

The frightened lizard darts behind a stone

First was the wind, now is the wild assault.

I wish this world would sink and drown again

So that we build another Noah’s ark

And send another little dove to find

What we have lost in floods of misery.

We have the torment of the ‘wild assault’ and also the potential power of the poem’s final ‘wish’: to ‘send another little dove to find / What we have lost in floods of misery’. Even in despair we are encouraged to remain focused on world building.

I mentioned that Carter’s is a poetry of involvement. Conversation can be folded into this idea. Last week I had the good fortune to speak to the Nigerian poet, Niyi Osundare, about his great respect for the work of Martin Carter. He has written about finding Carter’s work in Nigeria in the late 1970s at a time when his country was ‘reeling in the maelstrom of “post-independence disillusionment”’. He goes on to say:

‘It was the poetry of Martin Carter that provided the most immediate, most direct song for the barricades. ‘University of Hunger’ and many of his others passed from hand to hand and lip to lip. These poems were so lyrical, so relevant that many of us began to wonder why we hadn’t known their author much earlier.’

This powerful image of work being passed from ‘hand to hand and lip to lip’ is an image of poetry’s power of connection and conversation – the power to help us talk, to live together, and to think together. It is an image to hold onto as we remember Martin Carter.

Gemma Robinson teaches at the University of Stirling, Scotland and is the editor of University of Hunger: Collected Poems and Selected Prose of Martin Carter (Bloodaxe). For more information on Moray House Trust see https://www.morayhousetrust.com and https://www.youtube.com/@MorayHouseTrust. Niyi Osundare’s most recent collection of poetry is Green: Sighs of Our Ailing Planet (Black Widow Press).