By Nigel Westmaas

In the contemporary discourse regarding the Guyana-Venezuela boundary controversy, there is a marked absence of public attention to key events that have significantly affected this contested region of Guyana’s territory. Notably, there is a relative lack of attention given to previous instances of Venezuelan aggression against Guyana, such as the 1966 invasion of Ankoko Island in the Cuyuni River, during which Venezuela seized control of half of the island. Another substantial event is the 1969 rebellion against the Guyana nation state in the Essequibo region, commonly referred to as the “Rupununi uprising.”

Considering earlier evaluations, which included David Granger’s thorough analysis of the Rupununi event in the Stabroek News in 2009, this article seeks to adopt a more restricted perspective, that is, a succinct chronological account of the uprising primarily relying on Guyanese newspaper reports.

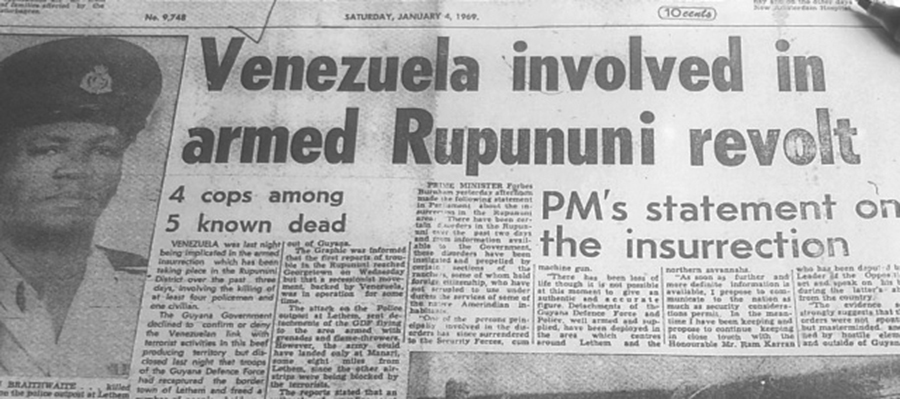

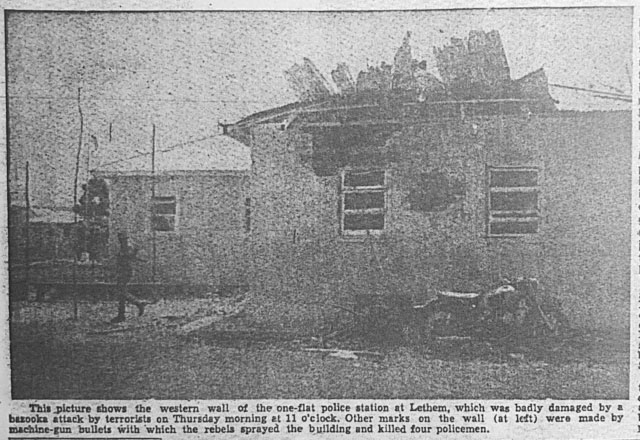

On January 2, 1969 the Guyana Graphic published a report implicating Venezuela in an armed insurrection in the Rupununi district of Guyana, resulting in the death of at least four policemen and one civilian. According to the report, the insurrectionists initiated the operation with a burst of gunfire that “sent policemen in the outpost of Lethem running from the station only to be moved mowed down in cold blood by men believed trained in the use of modern weapons.” The casualties included Inspector Whittington Braithwaite, Sergeant James Anderson, Constables James Mackenzie and Egbert Horton. Additionally, two civilians, Victor Hernandez of the Guyana School of Agriculture and Walter Michael, lost their lives in the incident.

The insurrectionists then began patrolling the area, capturing several civilians, including the district commissioner or other government employees, whom they confined in an abattoir. The rebel group also blocked airstrips in the area, held civilians hostage with “modern weapons,” including “submachine guns and bazookas.”

Police radio equipment was confiscated, disrupting communication between Lethem and Georgetown. However, information became public when two individuals, risking their lives, managed to depart with a small aircraft, which was fired upon as it took off from Lethem.

The initial reports of the uprising inn the press were characterised by caution: “The Guyana government declined to confirm or deny the Venezuelan link with terrorist activities in the beef-producing territory but disclosed last night that troops of the Guyana Defence Force had recaptured the border town of Lethem and stormed to free a number of people held as hostages.”

According to the Graphic, the “secessionist movement backed by Venezuela was in operation for some time.” The revolt led to the flight of hundreds of Amerindians to the Kanuku and Paka-raima mountains. Many returned to their villages after the GDF had crushed the rebellion.

The assault on the Lethem police station prompted GDF detachments from the Demerara bases to swiftly move into the area, equipped with grenades and flamethrowers. The army could have landed only at Manari, approximately nine miles from Lethem as they were hindered by rebel blockades on other airstrips in the area. Confined to Manari for nearly a day, the soldiers eventually reached Lethem and successfully reclaimed the town. Media reports suggested that a rancher and several civilians unsupportive of the foreign elements assisted the troops in their journey to Lethem. Upon arrival, the GDF discovered the bodies of four policemen and one civilian.

Col Desmond Roberts (a Captain at the time of the uprising) provided an account of the first GDF assault on the insurrectionists:

“After the nine-mile approach march from Manari to Lethem (since we had no trucks), we could see the rebels looking down at us from the water tower, as we adopted our final assault positions. My unit first cleared the houses along the main axis and then began moving quickly across the open ground leading uphill to the main rebel positions. Halfway up the long hill, we saw thick dust, created by several vehicles driving off: The rebels had opted to run rather than to stand and fight. Not a single round had been fired. Even though they had heavier machine guns, mobility and better knowledge of the ground, they were not prepared to fight an aggressive, organised and determined force.”

Other key GDF commanders involved in the operation included Col Ronald Pope, a British officer overseeing the Guyanese defence force, Col Cecil Martindale, Captain Vernon Williams and Lt Joseph Singh.

Reactions

Then Prime Minister, Forbes Burnham, in an initial statement on the events in the Rupununi, said, “the evidence so far strongly suggests that the disorders were not spontaneous but masterminded and planned by hostile elements in and outside Guyana.”

The opposition People’s Progressive Party (PPP), in a release, stated that the involvement of Venezuela in the uprising in the Rupununi area was to be strongly deplored, and expressed the hope that the Guyana government would take all necessary action to ensure the territorial integrity of this country. Then PPP General Secretary Janet Jagan noted however that there was “grave dissatisfaction among the Amerindian community in that and other areas and the frustration of these indigenous people was a factor not to be ignored.”

Eusi Kwayana, then head of the African Society for Cultural Relations with Independent Africa ASCRIA), in a press release stated, “Guyana is indignant at the murderous attempts made by an aristocratic clique of traitors in the Rupununi to seize power in the area on the orders of aggressive forces in Venezuela.” ASCRIA also called for military training of the youth and the establishment of “new communities in the interior in such a way as to enlarge the rights of Amerindian farmers and Guyanese pioneers”.

Uprising leaders

The leaders of the uprising were described as ranchers led by several prominent and wealthy families in the area, including the Harts and the Melvilles. The Christian Science Monitor described the Melvilles as “descendants of the original Scottish family that came out of then British Guiana at the turn of the century and began large-scale ranching in the Rupununi.”

One of the leaders of the revolt, Valerie Hart, speaking from Caracas where she had fled, told the foreign press of the key details of the operation. Hart said that the “rebels – between 40 and 50 men had planned to take over key points in the area quietly and then issue an ultimatum to the Burnham regime demanding independence.” Hart and her followers were apparently intending to announce her as leader (President) of an “Essequibo Free State” in revolt against the Government of Guyana. A boasting Hart declared, “we controlled the area for 24 hours before the intervention of Government troops and the start of the fighting.” She subsequently admitted, “we were not prepared to make a stand against the 200 troops sent by the government.” Hart, a candidate for the United Force in the 1968 general election was expelled by the party in the wake of the uprising and her declarations from Venezuela. In its press release, the United Force stated, “the executive of the United Force met this morning and categorically declared their complete condemnation of the subversive and treasonable actions of the ranchers and others in the Rupununi district” and expelled “forthwith Mrs Valerie Hart for her involvement.”

Meanwhile another leader, US citizen and Korean war veteran Jim Hart, who had fled into Venezuela after the revolt was put down, was still in a bravado state of mind and threatened to return to take Essequibo. On January 17, two weeks after the revolt, he insisted “we plan to return to Guyana because we have properties and families there. We will do so either peacefully or fighting, whichever way the Burnham government wants.”

The other leading member of the revolt Harold Melville also maintained that the revolt was not put down quickly as the government reported claiming that their (rebel) forces “struck in several points” blaming the failure of the revolt on a “radio message sent from Rupununi to Georgetown before the rebels had managed to secure all the strategic points.”

Valerie Hart – a main leader of the revolt

In his 2009 analysis, David Granger identified various factors contributing to the conspiracy and subsequent rebellion, encompassing economic, ethnic, political, legal, and strategic elements. Additionally, he highlighted Valerie Hart’s emphasis on the racial factor. According to Hart, the rebels aimed for “racial independence” in response to what she described as the “despotic policies” of Forbes Burnham’s “central government”.

The Prime Minister, for his part, addressed the nation with more details on the context and form of the assault and the motives of the leadership whom he described as “savannah aristocrats”. Notably he ascribed a linkage to Venezuela noting that “the Venezuelan press and radio were reporting an Amerindian uprising in the Rupununi and suggesting it arose out of the wish of these Guyanese citizens to come under the sovereignty of Venezuela.”

On January 9, the Guyana government sent a protest note to Venezuelan President Raul Leoni accusing his government of “iniquitous action” in what it deemed that country’s organisation of the Rupununi uprising with the object of advancing “its spurious territorial claims to the country.”

The accused

Twenty-two suspects implicated in the revolt were apprehended and formally charged with murder, a consequence of the fatalities involving both police officers and local residents in the affected area. These individuals constituted a portion of the approximately 300 people who had been detained on suspicion of participating in the uprising. Among the accused were two brothers connected to the “Melville clan”: Colin Melville who had surrendered to the security forces, and Keith Melville. They were named as “numbers one and two accused respectively.” The 22 accused were transported to the capital where, as reported by the Graphic, “anxious crowds” had congregated both inside and outside the Georgetown magistrates court compound from around 8 am with the aim of getting a glimpse of “the largest single group of men ever accused in the country of a capital offence.” Later in the month, 18 of the 22 murder accused were freed. A year later, according to Granger, “charges against the suspects who were remanded for trial in the high court were dismissed.”

Meanwhile, the Graphic reported that many Amerindians who had fled across the border to Brazil as a result of the uprising have since returned. The newspaper estimated that 60 percent of the approximately 13,000 Amerindians who had left their homes returned after the rebellion was suppressed. In addition, the District Commissioner for the Rupununi area, Motilal Persaud, who was compelled to join his staff and “lie prostrate on the ground outside his office after the ranchers had overrun the administrative centre,” indicated that “some Amerindians were brought to the border by the Brazilian army, and they were helped across the Takutu by our policemen.”

In the aftermath of the Rupununi rebellion, allegations of brutality by the GDF against residents surfaced. Three of the Hart brothers, who were actively involved in the revolt, asserted to reporters in the Venezuelan city of Bolivar that the GDF employed “brutal measures” to suppress the uprising. However, Col (Retired) Roberts, vehemently denied any accusations of atrocities occurring during the operation to put down the uprising.

In summary, the Rupununi uprising has left a legacy linked to the persistent Guyana-Venezuela border controversy. Additionally, its impact extends to the broader regional, ethnic, and political dynamics that have shaped the country since the event in 1969.

Timeline of events:

Jan 2 Rupununi uprising begins

Jan 3 Reports reach Guyana press. Prime Minister’s initial statement in parliament

Jan 4 Prime Minister Forbes Burnham addresses the nation on the “disturbances” in the Rupununi savannah

Jan 5 Reports that ringleaders of the uprising held; opposition PPP ‘strongly deplores” the events in Rupununi

Jan 6 Press reports that “uprising crushed, rebels flee”

Jan 6 United Force expels Valerie Hart while condemning the uprising

Jan 8 Protest note handed to Venezuela

Jan 9 Charges laid on 22 revolt suspects

Jan 10 Rupununi murder accused appear in Georgetown court charged with murder

Jan 11 Other rebels describe the government as “too brutal” in putting down the revolt

Jan 17 Rebel Jim Hart vows “we’ll fight” from Caracas

Jan 24 Eighteen Rupununi rebellion accused are freed

Sources:

Guyana Graphic, January 1969

David Granger, “The Rupununi Rebellion” Stabroek News, January 18, 2009

Col Desmond Roberts, letter to Stabroek News, 2005

Forbes Burnham, “Radio broadcast to the nation on disturbances in the Rupununi savannahs, 4 January 1969” in Destiny to Mould (1970)