At the end of the last day of the Second Test match, Tuesday, 19th April, 1988, Pakistan’s Captain Imran Khan thanked Lennox “Willie” Williams (the masseur who had been assisting his team since the commencement of the Guyana leg of the tour just prior to the First Test) and confirmed that he had been paid for his services. Williams returned to Guyana.

Friday, 22nd April 1988, First day of the Third Test match, Kensington Oval, Barbados. Pakistan made two changes to the team which played in the First and Second Tests; Batsman Ijaz Ahmed and allrounder Ijaz Faqih were replaced by batsman Ameer Malik and left arm fast bowler Salim Jaffer, respectively, while the West Indies retained the same XI from the Second Test. Skipper Viv Richards won the toss, and eyeing the green-top wicket, invited the visitors to take first strike.

Pakistan’s opening pair of Mudassar Nazar and Rameez Raja enjoyed their best stand of the series, adding 46 in a little over an over, before Ambrose’s yorker clean bowled Mudassar for the third time in the series. It was the beginning of the replicating pattern of the Second Test, with constant momentum swings. Pakistan were cruising in the final over before lunch, when an over-confident Raja (54) drove Benjamin to Greenidge at cover. 99 for two. Just after tea, the visitors were floundering at 218 for seven, when once again, wicket keeper Salim Yousaf intervened. Swinging, Yousaf struck two sixes and three fours while adding 67 with Wasim Akram in 50 minutes, before a missed hook resulted in a broken nose forcing him to retire hurt on 32, with the total on 285. Qadir, his replacement, continued in the same vein, as Pakistan crossed the 300 threshold just before stumps, eventually finishing on 309. Marshall, four for 79, and Benjamin three for 52, were the main wicket takers.

The second day’s play reflected how closely matched the two teams were, but by the close of play Pakistan had gained the upper hand. In a day, in which only 69 overs were delivered, the West Indies recovered from 21 for two, to 198 for three, thanks to Haynes (48), Hooper (54) and Richards (67). The introduction of Mudassar Nazar’s gentle medium pace after tea triggered the startling collapse, as the hosts found themselves in dire straits at the close at 226 for eight.

The third morning saw Marshall and Benjamin once again tormenting the Pakistanis, this time with their bats. With a series of scintillating strokes, the pair frustrated Imran and company whilst adding 57 off 9.3 overs, as Marshall raced to 48, with six boundaries and a cut for six over the Kensington Stand. The last pair of Benjamin and Walsh further compounded the visitors’ frustration, pushing the West Indies to within three of the Pakistan score by adding 23 precious runs at just under a run a minute. Imran and Akram were the pick of the bowlers with three wickets each. The match was down to one innings.

Once again, the momentum swung suddenly after tea as Pakistan slipped from the solid position of 153 for two to batting down the hatches at the close at 177 for six, with the entire top order back in the pavilion. Shoaib Mohammad followed up his first innings 54 with a patient three-hour-long 64, whilst adding 94 with Mudassar for the second wicket, and 53 with Miandad for the third, before giving Richards a return catch. Marshall then accounted for the dangerous duet of Miandad and Salim Malik. Imran and Akram held the fort going into the rest day.

On the fourth day, Imran, leading from the front, and Yousaf, batting with a broken nose, added 52 for the eighth wicket pushing the total to 234, before the latter, who was dropped first ball by Richards at first slip, fell via the same route, off Benjamin. Imran, 43, not out, guided the total to 262, leaving the West Indies the difficult task of scoring 266 to square the series. At tea, the hosts were motoring along at 77 for one, with Greenidge and Richardson, in sparkling form, laying the table for a solid chase. In keeping with the match’s post-tea momentum shifts, the West Indies found themselves in the difficult position of 154 for five at stumps with Richards, 26*, and Ambrose, 0* at the crease.

The final day commenced with Pakistan needing five wickets and the West Indies requiring 112 runs. It was not a day for faint of heart fans who must have lost all hope when Richards was bowled 34 minutes into the day’s play by Akram. 180 for seven, nightwatchman Ambrose having departed at 159. Dujon and Marshall pushed the score along, as fans throughout the Caribbean ceased all work and gathered around their radios. Tension was running high everywhere, with Pakistan appealing for everything. Qadir led a confident appeal for a catch off Dujon at forward short leg. Umpire David Archer was unmoved. Akram trapped Marshall LBW, his third victim for the morning, in an impressive spell of 12 consecutive overs. 206 for eight.

Benjamin joined Dujon, and promptly swotted Qadir for two enormous sixes, playing the mystery spinner with apparent ease, as the West Indies got to lunch with 33 required. Imran spelled Akram for two overs, but was ineffective, as the threat of Qadir diminished with each passing over. Imran replaced Qadir with Shoaib’s off-spin. Nothing worked, Benjamin, now the senior, clotted the winning boundary as hundreds of West Indians, Richards amongst them, charged onto the field. Benjamin, whose innings of 40*, included four boundaries and two sixes, in 96 minutes, and Dujon, 29*, in just over two hours had delivered the most improbable of victories for the West Indies during that period of dominance. The proud records of not having lost a series at home since 1973 and any series since 1980 and any Test at Kensington Oval since 1935 had been preserved.

Benjamin later recalled that he had heard Aamer Malik, who was substituting as the wicketkeeper for the injured Yousaf, telling Qadir (who he probably had difficulty reading), “legbreak, googly, flipper” and started repeating the order to himself. Fortunately for Benjamin, Qadir didn’t change the sequence.

The 1989 Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack stated, “The umpiring, except for a few debatable decisions, was good.” Imran, so close, but yet so far, agreed in part, “Unfortunately, during the second innings of the Bridgetown Test, we were disappointed. Three vital mistakes went against us.”

Aftermath A lack of decorum

Imran was frowned upon for his frequent habit of appearing in casual attire, slippers and short pants, when going out to spin the toss or attending press conferences. In addition, the Pakistan team did not warm themselves to the West Indies fans with their incessant appealing, repeatedly interrupting the game for unscheduled drink breaks, constantly changing gloves and bats on the field, and prolonged lapses for official refreshments.

Kensington Oval Tradition

“Tell your boys,” an ancient denizen of the ground rasped at every white man he could find who was not Tony Cozier, “that the last day at Kensington Oval always belongs to us.” Telford Vice, South African freelance cricket writer recalling [in the ESPNcricinfo series ‘The best I’ve watched, 24 Jan. 2010] South Africa’s collapse on the last day of the One-Off Test [a single match Test series] at Kensington Oval, 1992 (In Search of West Indies Cricket – The Boycotted Test Match, 19th March, 2023). Perhaps the longstanding inhabitant also preached to the disappointed visitors after the Third Test.

Legacy

Outside of cricket, Imran Khan enjoyed a flamboyant life. The only son of a civil engineer, he was raised in upper middle-class surroundings in Lahore, where he attended Cathedral High School and the world famous Aitchison College (founded 1886). There, no doubt, he would have heard of the famous words spoken by the then Lt Governor of the Punjab Sir Charles Aitchison – for whom the school is named – to the students in 1888, “Much, very much, is expected of you. I trust that you will use well, the opportunities here afforded you both for your education and for the formation of your character. …This is an institution from which you will banish everything in thought and word and act that is mean, dishonourable or impure, and in which you will cultivate everything that is virtuous, true, manly and gentlemanly.”

In England, he attended Worcester Royal Grammar School, a famous English public school founded in 1291, from whence he enrolled at Oxford University in 1972, where he read for the highly prestigious Philosophy, Politics and Economics degree at Keble College. As a precocious 18-year-old, Imran followed in the footsteps of his famous cousins, Javed Burki and Majid Khan, making his Pakistan Test debut at Edgbaston in the First Test of the 1971 Tour. It was another three years – missing three series – before he was selected again, playing all three Tests in England in the summer of 1974. After missing the 1975 two-match Test series versus the West Indies at home, Imran became a fixture in the Pakistan team, and was eventually elevated to the captaincy for the 1982 tour of England. Leading from the front, as he was bred to, Imran was hugely disappointed with their 2-1 defeat, despite garnering two Man of the Match awards and the Man of the Series accolade. He cited poor umpiring decisions for his team’s defeat in the series, choosing to overlook their oft times reckless batting and excessive over appealing.

During the 70s and 80s, Imran played first class cricket for Lahore, Oxford University, Worcestershire, Dawood Industries, Pakistan International Airlines, World Series Cricket (Kerry Packer), Sussex, and New South Wales. Under his bold leadership approach, Pakistan evolved into a world class unit, as Imran strove to have the best XI on the field at all times, even dropping his cousin Majid Khan during the 1982/83 six-Test home series against India. It was a decision that terminated Majid’s career and led to a two decades’ silence between the relatives. Following his aborted retirement plans, Imran led his country in five of the next seven series, between 1988 and 1991/92, beating Sri Lanka at home, losing in Australia, and drawing the other three encounters. In his penultimate Test series in late November/early December 1990, the West Indies rebounded from an eight-wicket loss in the First Test at Karachi, to win a low-scoring match in the Second Test at Faisalabad by seven wickets inside of three days. In the Third Test, in his hometown of Lahore, Imran held the West Indians at bay for just under five hours, giving strength and encouragement to the nightwatchman Masood Anwar, on his debut, as he stayed with Imran for three hours into the final day. Set 346 for victory, Pakistan finished on 242 for six, with Imran undefeated on 58 at the close. It was the third successive 1-1 result between the two teams, and the fifth series in which he had failed to conquer his nemesis. Imran played in 88 Tests, despite being away from the game for two years in the mid 1980s with a stress fracture of the shin. In his final ten years, he appeared in 51 Tests, averaged 50 with the bat and plucked wickets at the miserly rate of 19. He led Pakistan in 48 Tests, winning 14, losing eight and drawing 26. Imran exited international cricket on the highest of notes, leading Pakistan to victory over England by 22 runs in the 1992 Benson & Hedges World Cup (the Fifth World Cup), on 25th March, 1992, in Melbourne, Australia.

Following his departure from the cricketing arenas, Imran, with debonair good looks and his playboy reputation fostered by the British tabloids, remained in the world’s spotlight. Motivated by his mother’s death from cancer in 1985, Imran defied all the odds and witnessed his dream of building a cancer hospital to serve the needs of all Pakistani cancer patients become a reality on 29th December, 1994 with the opening of the Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Centre. Today, it is Pakistan’s largest tertiary care hospital.

A high-profile marriage to Jemima Goldsmith, the daughter of a wealthy British financier, in 1995, kept Imran in the news. In the 1990s he was UNICEF’s Special Representative for Sports, and served as Chancellor of the University of Bradford from November 2005 to November 2014. He ventured into the murky world of Pakistan politics, founding the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party in April, 1996, and served as the 22nd Prime Minister of Pakistan from 18th August, 2018 to 10th April 2022.

In his early retirement years, Imran penned opinion articles on the game for several British and Asian newspapers, and worked as a commentator on several British and Asian. Arguably, Imran is the best cricketer ever produced by Pakistan, evolving into a genuine fast bowler and one of the best all rounders of all time. However, his enduring legacy to cricket will be his campaign for the adoption of neutral umpires in Test cricket. Tired of criticism and accusations of home umpiring, Imran took the bold step of inviting two Indian umpires, Piloo Reporter and V K Ramaswamy to stand in the 1986 Test series against the West Indies. Bureaucratic delays prevented them from appearing in the First Test, but they stood in the Second at Lahore (won by the West Indies) and the drawn Third at Karachi. It was the first time since 1912, when England hosted the Triangular Test tournament, that neutral umpires had stood in a Test match. English umpires officiated in the three Tests between Australia and South Africa. Imran repeated the protocol for the 1988/89 series with India. English umpires, John Hampshire and John Holder, oversaw the four drawn Test matches.

The ICC soon realised that Imran had paved the way for the inevitable, and neutral officiating had become necessary to maintain the integrity of the game. One neutral umpire per Test was appointed on an experimental basis in 1992, and the system was adopted two years later. Coupled with this development was the evolution of the Match Referee in 1991/92. Commencing with India’s 2002 Tour of the West Indies two neutrals became the standard for Test cricket. Advances in technology, most notably the slow motion replay, led to the adoption of the third umpire, aka the TV umpire, and eventually the system of challenges and reviews. Today, we can look back at this radical change from the previously staid approach and point to Imran’s persistence to revolutionise the officiating of the game.

Here are two excerpts worthy of note from Imran’s 2010 MCC’s Spirit of Cricket Cowdrey Lecture at Lord’s, where he delved into his struggles to introduce neutral umpires, “ …and I remember whenever I used to talk about neutral umpires I always used to be told, ‘It all evens out in the end .’ This cliche, ‘It all evens out in the end’. Now I’ll indulge in just one other incident… And in walks Sir Vivian Richards [third morning of the Second Test, Port-of-Spain, 1988], West Indies tottering at 70..60 for three [makes a juggling motion with his hands].. something like that, then they lose another wicket, now they are 70 for four [actually 81 for four]. Now the whole ground, again pin drop silence. Everyone knew that what stood between us and a series win was Vivian Richards [pauses, extends his arms to either side]. We knew it, the crowd knew it, Viv certainly knew it [laughter from the audience], because the gum was being chewed at ten times the normal pace, the jaws were moving very quickly, you knew he was very nervous. So anyway [slight pause] but sadly the umpires also knew it [slight pause], and now here is an inswing bowler, who thought so many, so many times that there were LBWs which went against him, because I was an inswing bowler mainly, I don’t remember any of them, but I remember this decision as if it happened yesterday … I still remember this ball…I was bowling this outswinger, cross breeze blowing, to Viv you always bowled outswingers… when a bowler is bowling outswingers, you don’t take your front foot out too far, you are playing from the crease, you are waiting for the ball to do its work, he was playing from the crease… and then something happened, intentional outswinger, the ball pitches and comes back, not intentionally [right hand on chest]. The bowler doesn’t know it, neither does the batsman know it. Anyway, I still remember it was missing the leg and off stump, but hitting the middle… [laughter from the audience] …he got it right standing in front of the crease… I can picture it, middle stump being knocked out of the ground, hit him flush in front. We appeal [hands in the air] and we appeal and we appeal, because everyone knew everything depended on this decision, and I looked at the umpire and he wouldn’t look at me, he kept looking down, and he wasn’t given out. So Viv Richards went on to make a hundred… because if you believe the spirit of the game is to play the game fairly and you want accurate results, you must have, you must eliminate every chance of there being a wrong result [he was referring to the innovation of the referral system to the third umpire], that’s how you will find on the cricket field the atmosphere is very harmonious….I’m all for the use of technology to get fairer results.”

Willie’s lament

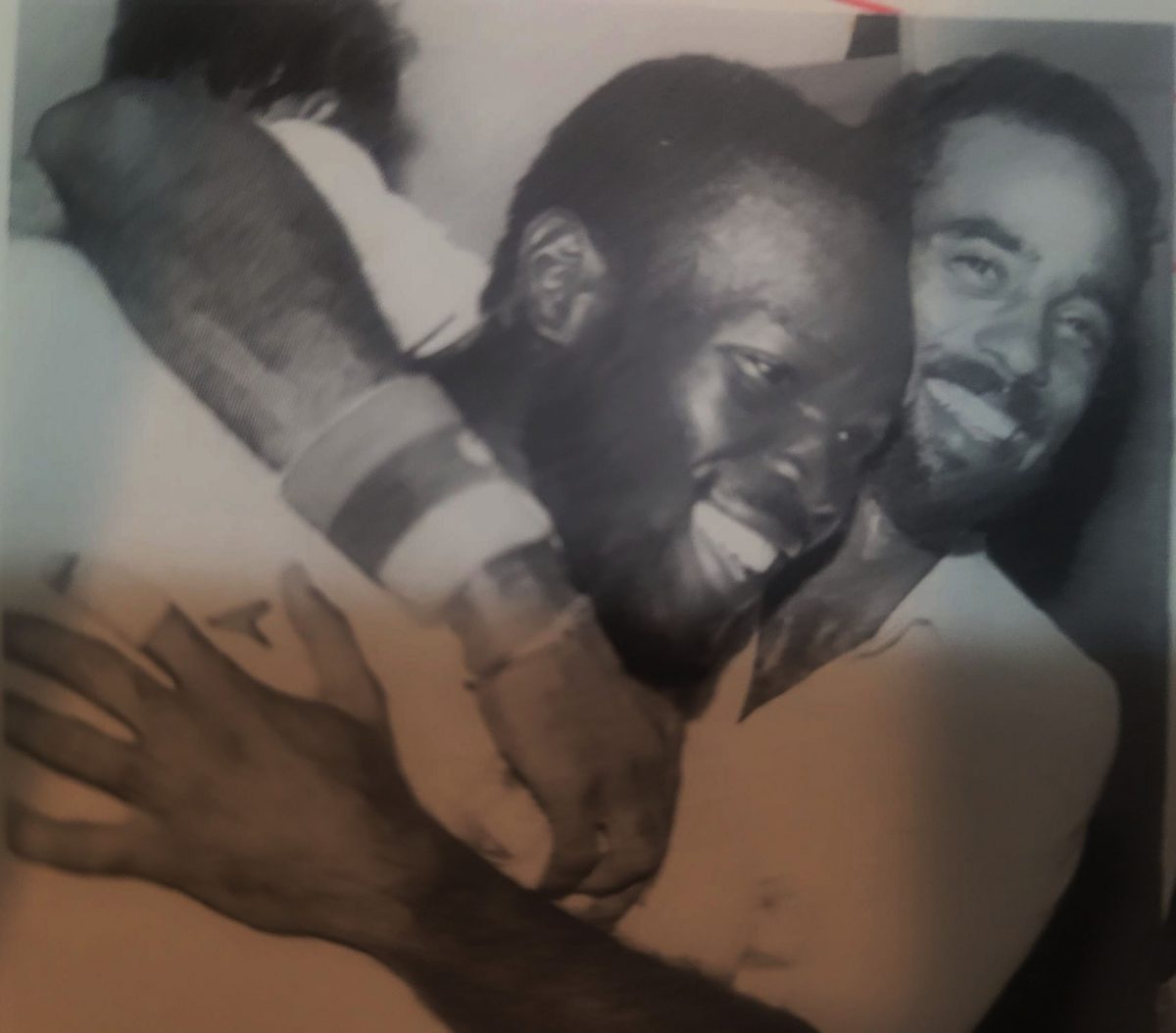

A few weeks later, I visited Willie and found him in anguish, still mulling over the Pakistanis’ decision to forgo him for the Barbados Test. “You saw [bearing in mind there was no television coverage back then] what happened to Pakistan on the last day? You know if I was there , they would have won, eh? You realise Imran couldn’t bowl for long on the last day. Probably was muscle bound. In the first two Tests, every lunchtime and teatime, as soon as they enter the dressing room, Imran would strip down and lay on the massage table – ‘Willie, back, arms, legs’ – and I have to rub him down quick, quick. Every time, he put on fresh clothes, drink a glass or two of water. Look, the man hardly eating, and then he gone back out on the field and bowling hard. Look, Imran tough bad, eh. The man is a real lion. If I was there, it would have been a different story…”