Protests and Pedagogy is a collective of Caribbean scholars, students, community members, writers, artists, and activists who initially came together in 2019 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Sir George Williams University student protest. We locate ourselves in the legacies of Caribbean diaspora and the CLR James study group in Montreal.

Protests and Pedagogy is a collective of Caribbean scholars, students, community members, writers, artists, and activists who initially came together in 2019 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Sir George Williams University student protest. We locate ourselves in the legacies of Caribbean diaspora and the CLR James study group in Montreal.

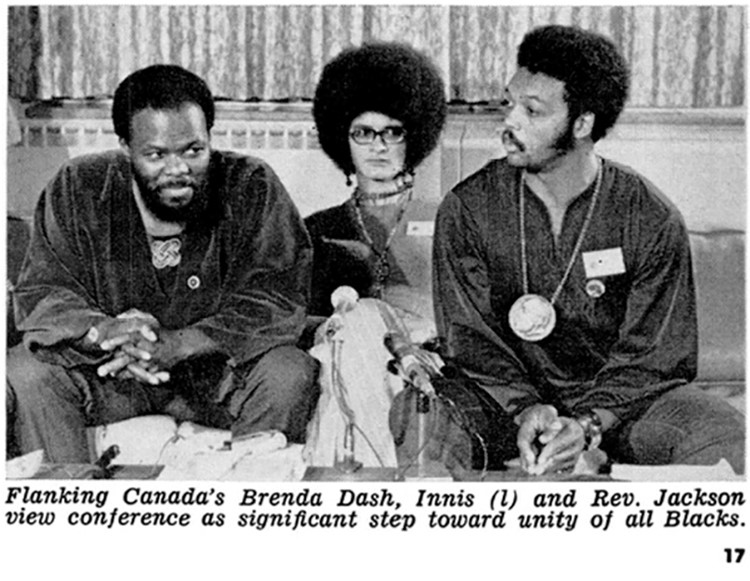

Canada does not often celebrate its Black heroes, nor the history of Black resistance in this country. One activist worth noting in the struggle for Black rights in Canada is Brenda Dash who was integrally involved in the largest student protest against anti-Black racism ever to happen in this country – the occupation of Sir George Williams University in 1969. She played a leading role as a student leader and spokesperson for the students in their quest for racial justice at the University and later Black rights in Canada. Dash passed away on November 29, 2023 at her home in Las Vegas. Although parts of her activism are known, her full story and the legacy of her activism is yet to be told.

In an interview with David Austin, intellectual Norman Cook singled out Dash as a kind of “Panther leader, a Black Canadian who had a following largely among other Canadian-born Black women”. She was viewed as a woman who played a prominent public role in 1960s Black politics of Montreal although it was largely a ‘boy’s game’ at the time.

Dash was born and raised in Montreal by parents who had immigrated to Canada from Trinidad and Tobago. She grew up as a part of Montreal’s Black community and later studied at Sir George Williams University and then McGill University. Her father worked as a railway porter, and her mother was active in the Coloured Women’s Club. As Dash said in Black Life: Untold Stories (“Revolution Remix,” available on CBC Gem): “When an immigrant comes, they don’t come for a party. They come for a better life, and they mean it. My father had experienced so much discrimination in Canada: we had to be better.” In the same episode, Dash tells us she developed a Black consciousness in childhood. She attended a Catholic School where the top student was given the honour of leading the Ascension parade. She came first in her class but was still put in the back of the parade. “I think all of the experiences taught me, my father was correct. My colour was going to be held against me, and I had to be better.”

So, it is not surprising that the racist treatment of Black and Caribbean students at Sir George Williams (now Concordia) University galvanized her.

She was there as a student protestor standing up against racial injustice on that fateful morning of February 11th, when a mysterious fire broke out in the computer centre that students were occupying. They were trapped; the doors locked. They had to use an emergency axe to escape. The police were waiting on the other side. The university administration had called the police, even though the students were under the impression that an agreement to re-examine the cases of racism at the institution was reached. 97 students were arrested including Dash. Dash describes all of this – the deception, lock-in, subsequent arrests, and negative, if not monstrous portrayals of the protesters in Canadian media – as contributing to a strong and cohesive unit of young people prepared to fight!

The arrested students were advised to plead guilty, but Brenda Dash, Rosie Douglas and Anne Cools – well-known student leaders of the affair – refused. As a result, Dash, along with Douglas and Cools, became visible and vocal leaders of the protest. Looking back in conversation with Concordia university researcher, Christiana Abraham in 2021, Dash said: “either the three of us should have been found guilty, or not guilty. You can’t have one of us guilty, one of us sort of guilty, one of us not guilty. Despite this, Rosie [Douglas] was given a little less than a two-year sentence, Anne received a six-month sentence, and I was fined. That is what happened—Canadian justice!” Yet, Dash also told Abraham that during the students’ arrest and jailing, the prison guards were afraid “we would turn the other prisoners into revolutionaries”. There was revolution in the air.

Despite efforts to contain and curtail their momentum, the Sir George Williams occupation was part of a wider movement of Black Power – the full effects of which are under-documented in Canada. Before and after their release, Dash, Douglas, Cools and other students went on speaking tours across the US and Canada, determined to correct media misrepresentations of a “destructive riot.” They went to Toronto, Ottawa, and Halifax, the latter where they met with Black activist Rocky Jones, and to the US where they met with Black Power organizers like Kwame Ture (Stokely Carmichael), and the Reverend Jesse Jackson. They took part in marches, spoke out on the unfair treatment of Black students in Canada, and made common alliances. Dash was a firebrand public speaker, which caught the attention of police and intelligence services.

Her life – like that of many others who had participated in the 1969 protest – was heavily impacted by her involvement with the event long after her arrest and the lengthy court trials that followed. Austin suggests that the Canadian state security apparatus took a special interest in monitoring Dash as a “Black Power radical”. She paid a high price for her courage. In the 1970s, she was frequently, in her words, “rounded up,” that is – jailed for participating in Black Power events or when there was a security scare such as the FLQ violence in Quebec in the 1970s. Even when she permanently left Canada to settle in the US, she was constantly stopped at the border, and often prevented from boarding planes. She had difficulty obtaining a green card to work in the US, because of her court charges in relation to her involvement with the student protest. Nonetheless, she persevered, becoming a manager for well-known musical acts, including Digable Planets, and singer-songwriters Brenda Russell, and Regina Belle.

Through Dash’s life, we remember the cross-border Black movements that marked a civil rights moment – across the US and Canada. Dash recounted the development of a Black consciousness and Black power movement in Canada of the 1960s and 70s and its transnational connections. In so doing she provided a glimpse of suppressed histories of Black student activism, and Canada’s own Black power movement.

The activism of Black students in Montreal also sparked protests in key Caribbean cities against Canadian imperialism. And following the 1969 Sir George Williams occupation, Brenda Dash, Yvonne Greer, and others started Uhuru, an important Black Community newspaper based in Montreal that circulated transnationally (through the diaspora), providing an important source of alternative news. The work of Dash, and others, had far and wide-reaching impact.

In 2019, Dash returned to Montreal to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Sir George Williams Protests at Protests and Pedagogy, a 2-week commemorative program of activities organised by a research collective comprising Concordia faculty and staff, activists and Black community members. Anyone who met her could not help but be struck by the way she personified dignity and self-assurance. In 2019, she offered us this reflection (published in The Fire That Time):

“All we started out to do was get six, seven students fair grades from one professor. That’s all we were doing. We had no idea that it would mushroom into this gigantic thing that changed all of our lives forever. In a reasonable atmosphere, this is an issue that should have been concluded in 24 hours or a week.”

Racism is the opposite of what a university should be known for. It is unreasoned. A younger generation of students and community members who attended the roundtables she participated in at Protests and Pedagogy, were stirred by the urgent imperatives of decolonization and Black Power that Dash was responding to as a young woman (only 23 years old at the time of her arrest). The audience was captivated by Black Caribbean diasporic women who were not afraid of militant actions, especially during an era when Black women’s radical actions were minimized, or their roles reduced to “helpers.”

The renewed transnationality of Black and feminist movements is a phenomenon to which Caribbean feminist thought and practice has much to contribute. This could mean new objectives, new strategies, and importantly, new outcomes in women-conscious organizing in and beyond Black Montreal.

Moreover, Brenda Dash’s life teaches us that activism is practical; it is intellectual; it is strategic; it is life-long and essential in propelling social change.

Although Concordia University offered an apology acknowledging the role of systemic racism in the 1969 student protest at Sir George University, Dash had little interest in the apology (too little, too late).

Her steadfast principles remain an inspiration to all of us.

Rest in power, Brenda Dash.