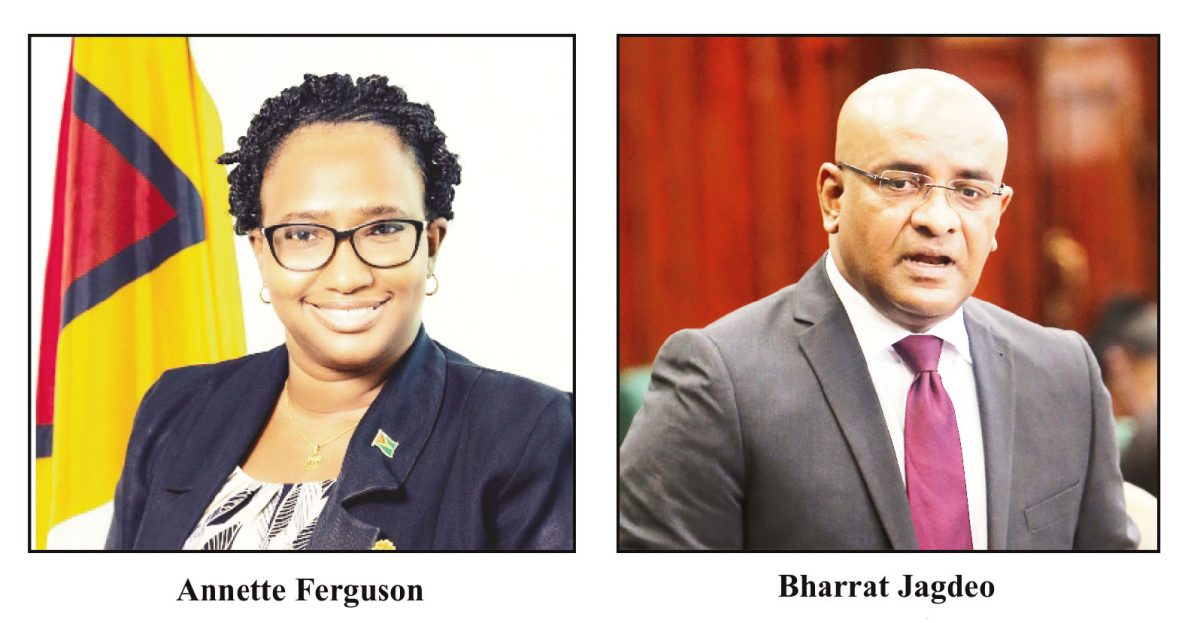

The Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) yesterday ruled that the Guyana Court of Appeal does have jurisdiction to hear an appeal filed by Vice President Bharrat Jagdeo, who has been trying to challenge a $20m default judgment imposed against him for not filing a defence in time to a defamation suit brought by former government Minister Annette Ferguson.

For the past two years, Jagdeo has been challenging that ruling of High Court Judge Sandra Kurtzious at every level of the local appellate system and in September of last year, he approached Guyana’s final appellate court—the CCJ.

Before the Trinidad-based court of last resort, he maintained the argument he did before the courts below, that the trial judge erred in entering a default judgment against him without considering all the grounds of his draft defence.

Back in September, the Guyana Court of Appeal dismissed motions which Jagdeo had filed against the order of Justice Kurtzious, while remitting the matter back to her for the assessment of damages; while going on to find that it did not have the jurisdiction to grant Jagdeo special leave to appeal.

Back in September, the Guyana Court of Appeal dismissed motions which Jagdeo had filed against the order of Justice Kurtzious, while remitting the matter back to her for the assessment of damages; while going on to find that it did not have the jurisdiction to grant Jagdeo special leave to appeal.

As it has now found, Jagdeo wanted the CCJ to rule in his favour that he did have leave to appeal to the Guyana Court of Appeal.

He was also successful in having the Court stay the hearing still pending before Justice Kurtzious for the assessment of damages to be awarded to Ferguson.

In a ruling of the CCJ handed down yesterday, the apex court said that in Guyana, decisions or judgments made by High Court judges can be appealed in the Full Court—a division of the High Court—and that appeals of the Full Court decisions are heard in the Court of Appeal of Guyana.

It went on to explain that where two Judges sit in the Full Court, there may be an evenly divided bench as was the case in Jagdeo’s matter; and parties must therefore look to legislation to determine the course of any appeals.

In the judgment yesterday, Justices Winston Anderson and Andrew Burgess, held that section 75 (2) of the High Court Act should be interpreted to mean that where there is an evenly divided Full Court, the appeal to the Full Court is dismissed and that the original High Court decision stands as the decision of the Full Court.

“Accordingly, that decision is subject to the regime of appeals as set out in the Court of Appeal Act,” they said.

“A contrary interpretation would forever immunise the decision of a single judge of the High Court from the reach of judicial review and would be inconsistent with the wording and objective of the section 75 of the High Court Act,” the judges went on to add in their written ruling.

The Court made the following orders in Jagdeo’s favour—that the application for special leave be granted and that the decision of the Court of Appeal that it has no jurisdiction to grant leave be reversed.

The CCJ has further remitted the case to the Guyana Court of Appeal for consideration whether to grant leave to appeal in all the circumstances of the case, while staying the hearing for assessment of damages against Jagdeo, pending the final determination of the matter.

The application before the CCJ was heard by Justices Anderson and Burgess, along with Justice Denys Barrow who had a dissenting opinion.

The Court noted that Jagdeo’s case was distinguished from its earlier decision in Guyana Sugar Corporation v Seegobin in which there was an attempt to appeal against the decision of one of two judges in a divided Full Court.

In that case, it was held that divided decisions are not directly appealable to the Court of Appeal.

Justice Barrow’s dissenting opinion followed the Seegobin decision.

He reasoned that where the decision of a single High Court judge is affirmed because there was an evenly divided Full Court on an appeal, there is no adjudication and so, there is no decision of the Full Court which can be subject to further appeal.

On the point of whether the Applicant was entitled to a rehearing, he stated that there is no common principle in common law courts that determines whether the failure of a divided court to agree, should result in a rehearing or not.

The dissenting opinion concluded that the legislation provides for adjudication by two judges, but with the option to apply for good reason for a hearing by three judges.

It was noted that an applicant should know in advance, and it was a material consideration for an applicant that if their application resulted in an even division of the Full Court, that meant they could go no further.

The legislation seemed to have contemplated that if there was an even division, the applicant would have failed to persuade two out of three High Court judges and should go no further. Based on the dissenting judgment, the application for special leave to appeal would be dismissed and costs awarded to the Respondent.

Appeals

Jagdeo had appealed Justice Kurtzious’ ruling to the Full Court which had delivered a split decision.

As a result, he then sought an order from the very Full Court to have his appeal of its decision be remitted to three fresh judges of the Full Court to hear and determine that appeal.

While that application was pending, Jagdeo also moved to the Court of Appeal seeking special leave to challenge the split decision.

Both Chief Justice (ag) Roxane George SC and Justice Priya Sewnarine-Beharry who heard the Full Court appeal refused Jagdeo’s application on the basis that Section 77 of the High Court Act—gives only to the Chief Justice—the power to appoint three judges instead of two to hear an appeal to the Full Court.

Following the Guyana Court of Appeal’s ruling, Ferguson’s attorney Lyndon Amsterdam, in a press release had said that the appellate court relied on Section 79 of the High Court Act and Sections 6(1)(2) of its own Act to find that it lacked the jurisdiction to grant special leave.

He had said in the release that this was underscored against the background of the Full Court refusing to give permission for a fresh appeal to the Full Court where three instead of two judges would hear the appeal.

Background

Justice Kurtzious had found from the pleadings that Jagdeo had defamed Ferguson. He had failed to file a defence within the time stipulated by the Civil Procedure Rules (CPR) and the default judgment was entered against him.

Though he acknowledges that his defence was not filed within the legal time limit, Jagdeo’s contention is that both he and his then attorney Anil Nandlall, now Attorney General, were busy with preparations for General and Regional Elections at the time.

He told the CCJ in his application, as he had all the lower courts; that because of being otherwise engaged with election matters, Nandlall “inadvertently” failed to file his defence which had already been drafted.

He also cited the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic at the time which he said added to constraints.

Through his current attorney Devindra Kissoon, Jagdeo argues that these are “reasonable explanations for the failure to timely file a defence.”

“We did not in any way intend to disregard the Court’s process, the surrounding circumstances being truly exceptional”, he said in his application before the CCJ.

Jagdeo’s contention had been that Justice Kurtzious erred by entering a default judgment against him without considering all the grounds of his draft defence, including but not limited to the defence of justification; by failing to appreciate the overriding objective of the CPR in ensuring justice between both parties.

Justice Kurtzious had imposed the default judgment against Jagdeo, because he had failed to file his defence on time, in the libel suit Ferguson had brought against him; which the Judge found did defame her, regarding certain statements he had made concerning her acquisition of land.

In her ruling, Justice Kurtzious had said that contrary to advancements made by Kissoon on behalf of Jagdeo, Ferguson’s application for a default judgment was well within the ambit of the CPR; while noting that her attorney had satisfied the requirements for the grant thereunder.

Justice Kurtzious had said she found the explanations proffered by Jagdeo for not complying with filing his defence within the 28-day time period specified by the CPR, to have been wholly “unreasonable.”