I heard it said recently that the average person spends eight seconds looking at a work of art. Eight seconds! What can one see of something that could have taken hours, weeks, months, or years to create in eight seconds? I count down using one Essequibo, two Essequibo, three Essequibo. Eight seconds does seem like enough time to decide whether to continue looking and that is about it. Looking means a volley of questions and possible answers. What am I looking at? What material was used? Is the technique paired with the material choices well suited? Are the techniques skillfully applied? How do I feel looking at this work? How do I feel walking around the work, through the work? What is the artist intending for me to experience? Has the artist succeeded? These are just a ramble of random questions that come to me as I look for seconds that have ticked away and turned to minutes.

It has often been stated that when the popular painter Paul Delaroche (1797-1856/9) saw the first daguerreotype, he stated “From today, painting is dead.” Whether this is so, the declaration points to the anxiety painters felt with the new technology encroaching on their territory. Ever since, painting has probably been declared dead far more times than the nine lives associated with cats. The daguerreotype and the subsequent developments of technology challenged painting’s strong association with mimesis and quickly thereafter the business of art seemed to embark on a self-conscious analysis of itself. What could painting do in the face of the new rapidly developing mimetic technology? Painting found itself in crisis.

In its many efforts to pull itself out of crisis, painting embraced new emerging political thought and resultant ideologies that defined art’s approaches within society. Painting also reflected on the past to find its future. One answer was non-objective art which began with a grounding in the communicative potential of geometry. Plato found geometry beautiful. Geometry does not attempt mimesis, and so it does not flirt with misrepresentations. Thus, for modernist painters geometric shapes could offer a pathway to enlightenment. As artist and co-founder of the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum in New York Hilla Rebay (1890-1967) beautifully stated: “[…] There is no representation of objects, nor any meaning of subjects in these paintings of free invention called non-objective art. They represent a unique world of their own, as creations with lawful organisation of colours, variation of forms, and rhythm of motif. These combinations when invented by a genius can bring the same joy, relaxation, elevation and animation of spiritual life as music. Knowledge of point and counterpoint never was necessary for anyone to enjoy the beauty of music. […]”

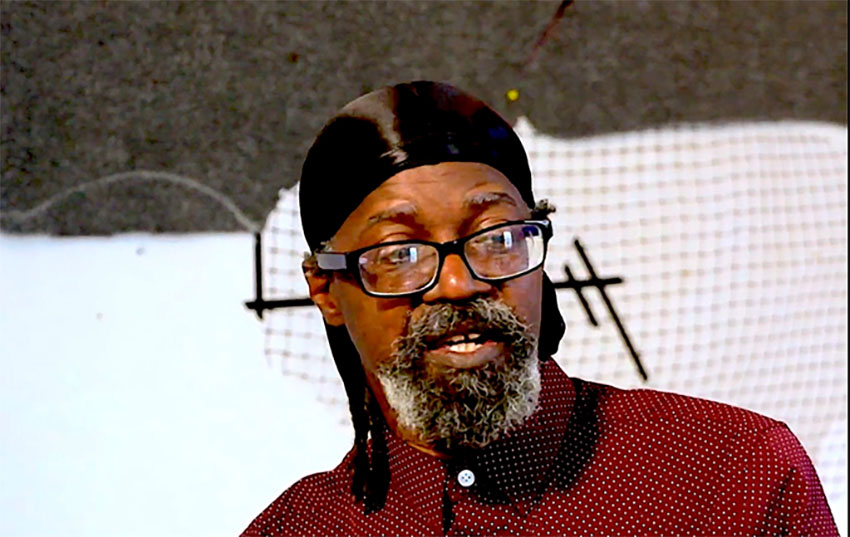

Standing before a Malevich or an El Lissitsky, therefore, requires a pause for thought, questions and answers, and of course the possibility of being affected. But what does this have to do with Guyana and Guyanese artists? Carl E Hazlewood (b 1951) left Guyana as a youngster, earned a BFA (Honours) from the prestigious Pratt Institute, and later an MA from the highly reputable Hunter College, CUNY. In 1973, Hazlewood also attended the Skowhegan School of Sculpture and Painting. In the years since his departure, Hazlewood’s connection to Guyana was largely maintained through his curatorial work at Aljira, a Center for Contemporary Art in Newark, NJ – an institution he co-founded in 1983. Exhibitions he curated at Aljira, provided select Guyanese artists at home and abroad with major space to show their work. However, despite his curatorial work on behalf of Guyanese artists, Hazlewood has stretched his art practice beyond the scope of what typifies Guyanese art. Figuration and landscapes do not define his work. Hazlewood’s compositions embrace hard-edge abstraction; therefore, precision and this is echoed often in the clarity of shapes, lines, colour, and their clear relationships with each other. As stated on the artist’s page of the Welancora Gallery website, “Hazlewood uses the structural language of abstraction as a clarifying act of progress in what he considers an unstable world. Through a suite of shapes and symbols, his work speaks to the power of resiliency through references to Anansi the Spider, a prominent character in West African and Caribbean folklore.”

Hazlewood’s compositions are sometimes more akin to sculpture than painting despite their failure to fully renounce two-dimensionality as they attempt to reject the limits of walls and occupy floors. The materiality of his compositions is also unexpected. There is paint but there is also felt, paper, string, and pushpins among other materials.

From February 27th to March 29th 2023, Hazlewood was hosted for a residency-exhibition at the Charlotte and Philip Hanes Art Gallery at Wake Forest University, North Carolina. He created a large-scale in-situ work in the Main Gallery, and exhibited a selection of completed works. Framing the work for the Hanes Gallery, Hazlewood notes:

“[…] Movement for a lot of us — people like me — from one place to another, from one social/political situation to another, is an inescapable part of our existence; from the enforced travel of the Middle Passage, and now in North America where one dreamed of escaping the vicissitudes of Colonialism and poverty. So, while the things I’m producing may seem a bit off-kilter, perhaps referential to a belated modernism, in reality it’s more intimate than that. The visual arts, poetry, literature, allow us to dream in metaphor, allow us to fashion something positive from our conflicted history. The vicissitudes of shared tragedy, disappointment, beauty, loss, and love can bind us even tighter to each other. It’s all about community, and genuine community is ultimately about love.” (https://hanesgallery.wfu.edu/portfolio-item/carl-hazlewood/)

Hazlewood’s compositions required that the eight seconds be turned into minutes and more.

(To be continued.)