(The content of this article is based on a presentation given by the author for the Guyana Institute of Historical Research on November 11, 2023, and is published in honour of Black History month.)

Damon, an eminent figure in the annals of Guyana’s history, emerged from Plantation Richmond in Essequibo as a pivotal force in the nation’s socio-political and economic evolution. His strategic deployment of active-passive resistance tactics not only challenged the status quo but also left a lasting impact on Guyana’s history. This general narrative explores the dynamics of the Damon-led rebellion, revealing the multifaceted interactions among key players such as the British Crown, plantation owners, the colonial administration, judicial authorities, and the newly emancipated workforce. The account is enriched by the invaluable insights of Hugh Tommy Payne, a renowned archivist and historian, whose meticulous research in Ten Days in August 1834 – 10 Days that Changed the World (2001) provides a detailed exploration of Damon’s life and the seminal uprising in Essequibo. Payne’s work offers a critical lens through which to view the confluence of local and global events that shaped this period, including the abolition of slavery and significant technological advancements, thereby framing Damon’s contributions within a broader historical and global context.

The Abolition Act and its implications

In Guyana, the shadow of the 1823 Demerara rebellion and the subsequent murder tragedy at Batchelor’s Adventure would have loomed large over 1834. The enslaved African population had long resisted the brutal system of slavery, and the enactment of the Abolition Act in 1833 was met with mixed feelings of jubilation and apprehension.

Harold Lutchman has argued that the abolition of slavery (and the onset of apprenticeship) in 1834 was a pivotal catalyst for social and economic transformation in British Guiana (Guyana). The Act’s significance lay not only in altering the legal status of the enslaved population but also in its broader repercussions. One notable perception emerging from this period was the knowledge that field labour was degrading and incompatible with the concept of freedom. Damon and his contemporaries were well-informed about the laws and advocated for equality before the law, showcasing their deep understanding of their rights and the injustices they faced.

In 1834, the mediated emancipation of enslaved individuals below the age of six within the British Empire was realised. Those aged six and above were classified as “apprentices,” mandated to undergo an apprenticeship with their former owners. As highlighted by Noel Menezes, the new apprenticeship regulations required the formerly enslaved to work under specified conditions on the estates—four years for artisans and six years for other labourers.

In compensation for the loss of their “property,” slave owners throughout the colonies received financial restitution from the British government, amounting to approximately £20 million—a considerable sum at the time. This compensation was apportioned based on the quantity and assessed value of the enslaved each owner had relinquished, now central to modern debates surrounding reparations, highlighting the historical context of financial restitution in the aftermath of slavery.

The apprenticeship development was scheduled to conclude on August 1, 1838, marking the date when all enslaved individuals in the British Empire were to attain “full freedom”. During the apprenticeship, labour was unpaid, except for instances where work exceeded seven and a half hours in a day. In such cases, apprentices were eligible for overtime compensation, not for the entire day’s labour, but solely for the hours worked beyond the standard seven and a half. The British government was ultimately responsible for overseeing the apprenticeship system. It appointed special (stipendiary) magistrates to the colonies to ensure the fair treatment of apprentices and to resolve disputes between apprentices and their former masters. These magistrates were tasked with enforcing the regulations of the apprenticeship system, including the provision of overtime compensation. However, the number of stipendiary magistrates was generally insufficient to effectively oversee the apprenticeship programme, and many tended to align with the preferences of the planter class.

The commencement of the apprenticeship system obviously sparked significant discontent among the planters, who were frustrated with the changes imposed upon their traditional way of managing labour. This dissatisfaction was not only directed towards the new system itself but also towards anyone associated with its implementation, including the colonial authorities such as the governor. In reaction to these developments, certain planters employed provocative and coercive strategies against the previously enslaved apprentices. These extreme actions encompassed tearing down the apprentices’ homes, sometimes with the occupants still inside, and obliterating fruit trees that were crucial for their sustenance and supplies.

In Essequibo, one of these repressive measures would lead to one of the most famous acts of rebellion in Guyana’s history. This response of the planters occurred on Sunday, August 3, when Charles Bean, a planter from Richmond plantation in Essequibo, along with several other planters, deliberately killed 65 pigs owned by the newly apprenticed labourers. This act was not only a direct blow to the economic well-being of the apprentices but also carried symbolic aggression. Such actions were intended to instil fear and remind the apprentices of the planters’ power, underscoring the ongoing struggle and resistance faced by the newly freed individuals in asserting their rights and autonomy in the post-abolition period.

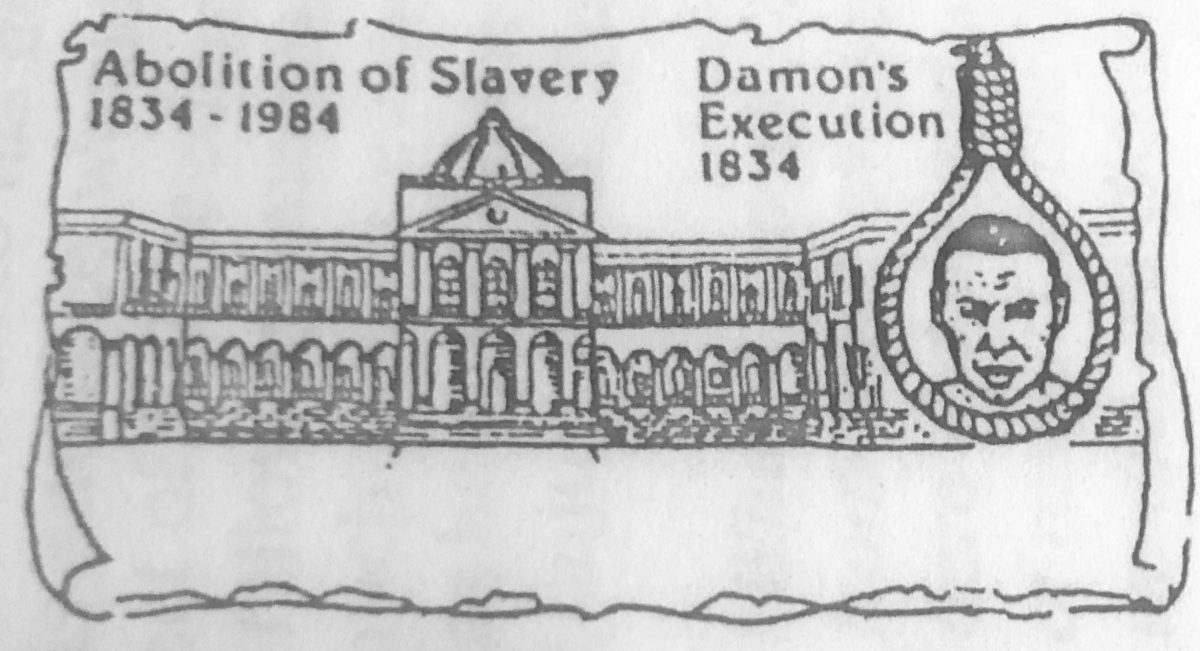

The Damon monument

The Damon resistance

The Damon-led resistance emerged as a seminal episode of civil disobedience, epitomised by his charismatic leadership. He galvanised a diverse assembly that eventually mushroomed to encompass 700 individuals, unified by a shared vision of justice and equity. This congregation found solace and strength within the hallowed confines of the Trinity churchyard in La Belle Alliance, Essequibo. Commencing on August 8, the churchyard was transformed into more than just a gathering space; it became a symbol of communal solidarity and a stage for non-violent protest against systemic oppression.

The plan involved a peaceful occupation of the churchyard, a bold declaration of their grievances and a plea for governmental intervention. The atmosphere, often punctuated by the resonant voices of Damon and other prominent members of the group, was charged with a palpable sense of purpose and resolve. A defining moment in the resistance was when Damon hoisted a flag—a potent emblem of their collective aspiration for autonomy and emancipation from the draconian grip of the plantation elites.

Under Damon’s indubitable leadership, the group not only occupied the churchyard but also engaged in symbolic acts that underscored their unity and determination. Damon notably took it upon himself to ring the church bell under the cover of night. This act served as a clarion call to his followers, a reminder of their shared commitment. This demonstration concluded only with the personal intervention of Governor Carmichael Smith. Although many dispersed following the governor’s address, the influence of the plantation owners led to the arrest of key figures, including Damon.

The repercussions

Damon faced trial, was unjustly convicted of a serious offence, and was sentenced to death. His peers suffered different fates; while some were exiled, the leaders among them faced harsh sentences in Georgetown, and four others sentenced to “transportation” (a term used to describe exile at the time), originally to New South Wales, Australia. However, their sentences were eventually commuted, and they returned to Guyana, resuming their roles as apprentices.

The La Belle Alliance revolt had significant repercussions, extending to the press, marking one of the initial media confrontations stemming from the protest at La Belle Alliance. The act of resistance highlighted the sharp divisions between the planters and the Governor, leading to divergent narratives in the Royal Gazette and the Guiana Chronicle. Despite Damon’s execution in October 1834 for his role in the revolt, the planters deemed the Governor’s response inadequate and clamoured for stricter penalties. The Governor’s decision to pardon other rebels on the same day as Damon’s execution elicited a fierce critique from the Chronicle, which lambasted Governor Smyth with “an attack of the utmost ferocity.” In retaliation, the Governor pursued a libel case against the newspaper, which ultimately led to the editor’s acquittal on the grounds that Smyth had previously affirmed “the freedom of the press in a Militia General Order of 31st December, 1833.”

The execution

Press coverage extended to the execution itself, with the Royal Gazette providing a detailed account. The Royal Gazette reported that a large crowd gathered to witness Damon’s execution, and maintained “a respectful composure appropriate for such a grave event.

“The behaviour of the unhappy man since his conviction has been of a very unsatisfactory nature to his spiritual guide, who found him in a contrite and humble mind, willing and anxious to receive Christian instruction and consolation, which can only adequately prepare an individual in the prime of his life to meet the resignation of a sudden and disgraceful death. With the exception of considerable nervous excitement, which was occasionally visible, his demeanour on the day of execution was calm and firm, and he walked from the jail to the new buildings with a steady step, which, however, vacillated a little when the scaffold met his eye. He soon recovered, and upon reaching the steps, ascended them rapidly.”

According to the Gazette, after Damon’s indictment was formally read, “the unfortunate culprit requested of the high sheriff permission to address a few words to the surrounding multitude”.

Damon’s last words were delivered to the assembled crowd from the scaffold at the Public Buildings on October 13, 1834. These words likely reflect a European interpretation or rendition of what Damon actually said, but they still offer an “eyewitness” perspective on his remarks.

“What I bin do, is no different from what everybody who been dere did do and we bin do it out of respect for the Governor. What we did we did for good and I can’t see why de bad dey. But suppose it right or suppose it wrong, suppose I guilty or I not guilty, it is no matter now. I condemn to die and I satisfy. Yes! I satisfy!”

Damon’s final statement, proclaimed from the scaffold, was remarkable not only for his exceptional bravery in the face of death but also for the historical importance of his remarks, which were subject to an effort to document the statement he made in the Creole language he used.

This record of a leader using the common language underscores an unintentional yet pivotal moment of cultural recognition in 1834.

The execution of Damon also echoed the tragic fate of Fortuin, a prominent figure in the 1763 rebellion, who endured a brutal execution in 1764. Despite the horrific torture inflicted upon him, including the removal of his skin with hot iron rods, Dutch records highlight Fortuin’s unwavering fortitude throughout the ordeal.

For his part, historian Henry Dalton remarked that Damon’s execution represented, “the last homicide committed in the British West Indies in defence of slavery.”

Damon’s legacy

Damon’s legacy continued to resonate, particularly as Emancipation Day was celebrated on August 1, 1838, four years post his execution. The journey towards freedom, however, did not end with emancipation; it was marred by ongoing racism and systemic barriers that sought to maintain a semblance of the old servitude.

But the resilience and creativity of the formerly enslaved were evident in the early 1840s as they pioneered the village movement in Guyana, laying the foundations for community self-sufficiency and autonomy.

In 1985, recognising the profound significance of Damon’s passive resistance and its enduring impact, the Regional Development Council of Pomeroon-Supenaam (Region Two) made the decision to honour his revolutionary stance dating back to August 1834. To bring this tribute to life, a monument was commissioned, crafted by renowned Guyanese sculptor Ivor Thom, then a member of the Guyana National Service. This artistic endeavour reached its completion in 1987, with Claude Geddes, then the managing director of Brass Aluminum and Cast Iron Foundry, entrusted with the task of casting the monument in bronze.

On July 25, 1988, the monument was prominently displayed on a low bed trailer north of the parliament buildings in Georgetown, where it remained accessible to the public for 24 hours. Subsequently, the monument embarked on a journey from Georgetown to Essequibo. On July 31, 1988, Anna Regina was the scene of a significant unveiling ceremony attended by Desmond Hoyte, the then President of Guyana, alongside members of the diplomatic corps. The event also saw the participation of international guests, including General Yakubu and Mrs Gowon from Nigeria, who visited Guyana to join in the celebrations marking the 150th anniversary of emancipation.

The inscription on the monument reads:

“On August 8th 1834 Damon demonstrated with 700 others against apprenticeship. Barricaded himself in Trinity Churchyard at La Belle Alliance he hoisted a flag of freedom and was later arrested and tried in Georgetown for inciting rebellion. He was hanged publicly outside the public buildings Georgetown on October the 13th 1834.”

Beyond the monument, there are various ways to pay tribute to Damon, a pivotal figure in the history of Guyana. Damon’s legacy is interwoven with the wide-ranging narrative of global civil disobedience and the extensive continuum of Black liberation movements worldwide.

His profound impact and dedication to peaceful protest are especially honoured during Black History Month in February. This period serves as an opportunity to celebrate and recognise the significant contributions of individuals and movements that have been instrumental in advancing civil rights and social justice. Damon’s legacy resonates in the lives and actions of influential figures such as Ida B Wells, Fannie Lou Hamer, Martin Luther King Jr, and numerous others, reflecting its enduring relevance in contemporary discourse.