Clem Seecharan’s “Cheddi Jagan and the Cold War, 1946-1992,” unfolds as a Tolstoyan epic across 743 pages (713 excluding the bibliography and index). In today’s era, dominated by the superficial succinctness of X and TikTok, this detailed study on Cheddi Jagan, a central figure in Guyanese politics, emerges as a crucial counterbalance to the trend of simplifying complex topics into brief soundbites and thereby glossing over the complexities of historical narratives.

This latest addition to Seecharan’s prolific and acclaimed publication history continues his exploration of valuable narratives, particularly charting the Indian Guyanese experiences and contributions across a spectrum from sports to political and social achievements. Spanning works from “Bechu”, “Tiger in the Stars, and “Mother India’s Shadow over El Dorado” to “Jock Campbell,” and his cricket tomes, Seecharan now turns to a more perilous task of dissecting a politician whose legacy still looms large over the present-day landscape.

The detailed exploration of Cheddi Jagan’s political career from 1946 to 1992, as presented in Seecharan’s 16-chapter work, not only highlights the Guyanese politician’s steadfast commitment to Marxism-Leninism and its ramifications on Guyana’s socio-political fabric but also his navigation through the Cold War’s complex geopolitical terrain, influenced by both Western and Eastern blocs. This extensive volume underscores the importance of depth in historical analysis by engaging with the multifaceted nature of Jagan’s political stance and its impact both in Guyana and internationally. Given the complexity of the subject, the book in its entirety symbolises the inherent challenges in interpreting historical figures without bias. Unsurprisingly, since its publication, it has ignited swift and fervent reactions, with critiques focusing on the perceived intent of the author to cast Jagan in a somewhat negative light. Likewise, even an extensive review can only touch the surface given the volume’s sheer size.

In researching the workings of Guyanese political dynamics, Seecharan presents a comprehensive analysis of Cheddi Jagan’s political journey in the Cold War era, including his confrontations with his main adversary, Forbes Burnham, and the People’s National Congress (PNC). The exploration also encompasses Jagan’s constitutional and electoral hurdles, marked by his repeated victimisation through rigged elections, his contentious battle for Guyana’s independence, and his complex navigation among British and American power brokers, including colonial governors. Additionally, the volume scrutinises his strategic and sometimes inadvertent leveraging of racial and ethnic support, as well as his extensive connections within the Marxist-Leninist sphere.

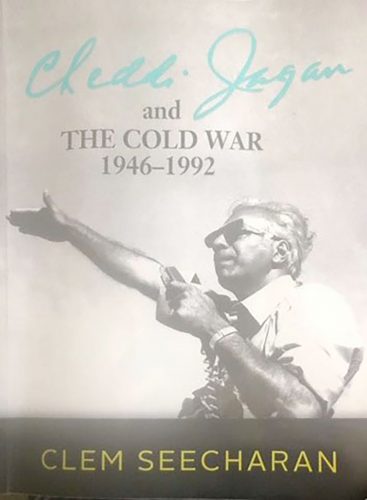

The imagination of the book is immediately evident in its cover design, which captures a quintessential pose of Jagan, frequently seen at public meetings, hands pointed outward to the horizon, embodying the subject’s vitality and passion. The inclusion of Jagan’s signature in green on the cover, contrasting with the book’s title, subtly reflects the book’s portrayal of Jagan, matching, in a sense, empathy with critical analysis within the narrative.

Technique-wise, Seecharan adeptly harnesses the power of extensive quotations, allowing individuals and organisations to express their thoughts, experiences, and emotions in their own words. This approach lends authenticity to the narrative but also serves a dual purpose: it establishes a robust body of evidence while meticulously crafting the historical record. By doing so, Seecharan ensures that the narrative remains deeply rooted in personal testimonies, official documents, secondary sources, and declassified intelligence records, offering readers an intimate glimpse into the lives and times of Jagan amid multiple other personalities and organisations.

These carefully marshalled notes do more than just relay facts; they capture the essence of the period, reflecting the societal, cultural, and emotional landscapes of the time. This technique enriches the historical context and enhances the reader’s understanding, making the narrative more engaging and impactful. He also balances thorough analysis with the readability factor so as not to overwhelm or overinform (although he does do so in some sections) the reader.

In colonial Guyana during the 1920s to 1940s up to the formation of the Political Affairs Committee in 1946, the societal fabric was woven with threads of sometimes conflicting nationalisms, primarily among the African and Indian populations. These identities, shaped by the legacies of slavery and indentureship respectively, led to the development of distinct movements that sought recognition, rights, and autonomy within the colonial structure. The juxtaposition of accommodating and duelling African and Indian political and social organisations and figures continually in the book highlights the complexities of colonial society, where the struggle for liberation from colonial rule was intertwined with the challenge of navigating inter-ethnic relations, living conditions, and nationalist aspirations.

Seecharan adeptly navigates the shades of Jagan’s appeal in his book, set against the context of prevalent indifference or outright hostility towards communism. He vividly illustrates how communism was “largely incomprehensible to Jagan’s supporters,” yet, despite this, Jagan succeeded in preserving his supporter base over decades of his commitment to Marxism-Leninism.

The emphasis on Janet Jagan, Cheddi Jagan’s wife and key political collaborator, as well as the influence of figures such as the Jamaican British-based communist Billy Strachan, Fenton Ramsahoye, Ranji Chandisingh, and others, is notable. However, the text leaves readers desiring Seecharan to also explore the wider and later (closer to the modern period) network of influencers and advisors (like Feroze Mohamed who is mentioned) who impacted Cheddi Jagan’s later political evolution, albeit still strictly leaning on Marxism-Leninism in the advanced Cold War era.

Seecharan hints at, but does not fully discuss, the role of economic incentives in Jagan and the PPP’s alignment with the Soviet bloc, leading to speculation about the true nature of this association. Was this partnership fundamentally a strategic manoeuvre to enhance the party’s operational capabilities under the facade of ideological commitment, especially when considering the provision of support for printing and other resources? This angle suggests the exploitation of Soviet financial aid for such purposes. Nonetheless, the author, backed by substantial data and evidence, ultimately posits that the affinity for Soviet and Cuban communism was genuinely fervent, despite recognising economic factors like the contributions like Gimpex, the party’s principal financial resource and printing presses.

The book offers a direct critique of Jagan’s actions, supported by evidence yet often presented through a sympathetic lens. Despite his incessant determination of the historical errors of Jagan’s Soviet affiliations, he is portrayed in the book as a politician whose honesty stemmed from his commitment to the working class, viewing communism as the most viable means for the working class as the following quote instructs: “whatever Jagan’s limitations as a politician, his capacity for hard work, honesty of purpose, incorruptibility, and sheer indefatigability (based on his belief in the tenets of Marxism-Leninism) rendered him a unique politician in the history of the region- possibly in the British Empire.”

Exploring the political shadows

Seecharan intersperses historical bites throughout the text that highlights lesser known aspects of Guyanese political and social life in the period. These insights, often overlooked in broader historical accounts, provide fertile ground for further scholarly exploration and could significantly enrich our understanding of Guyana’s complex past. One such example is the book unveiling a fascinating conversation between Henry Kissinger and Fred Wills, a former Guyana Foreign minister, concerning race relations in Cuba. This dialogue is particularly intriguing; at one point, Kissinger even accused Wills of harassing the US ambassador in Georgetown. This exchange sheds light on the complexities of international diplomacy and the tensions that can arise between nations, especially on sensitive topics such as race.

Another intriguing aspect of Seecharan’s research is the emphasis he places on the pivotal Birch Grove (England) summit meeting between British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan and US President John Kennedy that, according to the author, effectively sealed Jagan’s fate as a pariah in the ‘West’ from the early 1960s. Additionally, the book highlights Jagan’s interactions with Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s sister, MI5’s surveillance of both Cheddi and Janet Jagan, and other pieces of information not thoroughly documented in other analyses of the Cold War period and Guyana’s politics.

Seecharan likewise highlights the role of “Lascar”, the M15 (British intelligence) spy, who frequently eavesdropped and monitored the movements of Jagan, his party comrades and British communists, who worked out of the Communist Party of Great Britain’s office in King Street. London where Jagan and his Guyanese and British comrades would frequent.

At times, Seecharan’s treatment of specific topics are unnecessarily repetitive. For instance, Ranji Chandisingh’s defection to the PNC is repeated. Additionally, the recounting of Janet Jagan’s account of Sidney King’s extended stay in Eastern Europe during the 1950s is also repeated, as is the report of “Lascar’s” interception of the conversation between Jagan and the British communist Palme Dutt. There are further instances of repetition, suggesting that several sections or chapters could have been efficiently condensed into a single thematic chapter.

Unspoken signals and oversights

Seecharan often interprets racism or ethnic division in Guyana as being confined to explicit expressions during elections or through public political discourse, neglecting the importance of examining below the surface language and signals Jagan and Burnham (and their respective parties) utilised to subtly address their followers. Similar to how terms like “affirmative action” and “welfare” serve as coded messages in the United States, Guyana has witnessed its own form of communication in settings where racial provocations are not immediately obvious and acted on more freely in ethnic enclaves and “out of earshot”. While not directly implicating Jagan (although Seecharan does provide an extract from a distinctly racial speech by Jagan in 1964), it is suggested that there could be situations where the actions of senior figures and supporters are influenced by indirect signals from their leader, leaving the latter free from public and ethical accountability.

While the author critiques the cooperative dimension of the early village movement’s failure, there is some oversight in not addressing the wider context of racial hostility African Guyanese encountered in the immediate post-emancipation period. This hostility was not limited to restrictions on the village movement but a constant stream of hindrances including the imposition of unjust and malicious taxation, barriers to accessing crown lands, and overt and covert white supremacist racism, which severely hampered their economic potential and ability to transform their livelihood in both urban and rural economic sectors. The reduction in wages and general economic malaise for African Guyanese workers sparked strikes and disturbances in both the 19th and 20th centuries.

The author initially groups the PPP, PNC, and WPA as “Marxist-Leninist” parties but later clarifies their distinct ideologies. The WPA aligned more with “new left” Marxism than Marxism-Leninism, had ties with the Socialist International, and lesser connections to the Soviets or Cubans. The PNC claimed to be Marxist-Leninist but balanced Western and Eastern influences in its policies. The PPP, driven by Jagan’s strong support, was the most explicitly Marxist-Leninist of the three.

The author’s portrayal of Burnham primarily as a clever orator, manipulator, and dissembler seems to overlook an opportunity to also examine the pressures he faced, including those from his Afro-Guyanese constituency, his influences (apart from the ideological west and Communist east) and his entrapment, similar to Jagan, in a situation eloquently described by Martin Carter, with an eye to the respective ethnic bases of Burnham and Jagan, as “leaders who follow from in front.”

Although not necessarily germane to his focus the author made a notably cryptic comment, describing the Grenada revolution as “ridiculous” without providing further explanation or context. This leaves the reader to ponder the intended meaning behind such a terse assessment. Was the author commenting on the abrupt end of the revolution in 1983, precipitated by internal conflicts and strife? Or was the reference more broadly aimed at the entire revolution itself? If the comment is intended to encompass the revolution in its entirety, such a characterisation could be deemed unjust. It overlooks the widespread participation in and popularity of the revolution among the Grenadian people, particularly in light of Eric Gairy’s oppressive dictatorship. The revolution, before its premature demise, represented a significant movement against authoritarian rule, and to dismiss it summarily as “ridiculous” fails to acknowledge the complex motivations behind it and the genuine desire for change among the Grenadian populace.

Assessing legacy

Ultimately, the true value and significance of a book are often not recognised in the present but over time. While we await history’s verdict, the captivating breadth of its subject matter undeniably positions it as an authoritative analysis of the central aspect of Jagan’s political career—his pivotal role in Guyana and, by extension, the broader region and the Americas.

Overall, Seecharan imparts a vital moral lesson regarding the evaluation of any Guyanese public figure’s political successes and shortcomings. In sum, that it’s possible for a historian to offer critiques of a public figure while still acknowledging their overall contributions and accomplishments in holistic form.

To challenge or undermine the narrative presented by Seecharan, as well as the established narrative of US and British antagonism towards Jagan during the Cold War, would be comparable to attempting to extract a single thread from a densely woven tapestry of evidence and party propaganda that has reinforced this perspective for decades. This is underscored by the author’s tongue-in-cheek remark that even those with official credentials persist in refusing to label Jagan as a communist.

The last word can be attributed to Martin Carter, arguably the most insightful and deepest of all Guyanese thinkers. Carter recounted a conversation, or some variant thereof, in which he was asked whether India would have achieved its independence sooner if Mahatma Gandhi had not committed to non-violence. The response: “Then he would not have been Mahatma Gandhi.” In a similar vein, Seecharan implicitly recognises in his book that this principle applies to Cheddi Jagan and his legacy.