Just over one week ago on March 8, Guyana-born artist and photographer Dr Ingrid Pollard MBE (b. 1953) was named the winner of the 2024 Hasselblad Award. The prize is the world’s top accolade given to a living photographer. In addition to receiving 2 million Swedish kronor (approximately US$195,000), Pollard will also receive a Hasselblad camera. Later this year, on October 11 when she receives her award, an exhibition of her work will open at the Hasselblad Center, Gothenburg, Sweden, and will be accompanied by a substantial publication. Pollard is the 44th Hasselblad Award winner and consequently, joins the illustrious list of past awardees which includes Americans Cindy Sherman, Nan Goldin, and Carrie Mae Weems; German Wolfgang Tillmans and Chilean Alfredo Jaar, each of whom stands out in art’s histories.

The award citation reads as follows:

“In her four decades of practice Ingrid Pollard uses photography to question deeply ingrained social and cultural constructs behind race, identity, community, and gender. Her work reveals subtle and starkly evident injustices through her engagement with the British landscape, iconography, and identity, as well as challenging the medium of photography and its history. “Formally her work combines portraiture, found archival material, objects and text to produce complex installations. Born in Guyana and raised in Britain, she has consistently engaged with colonial history and how it continues to impact society, both in her artistic practice and as an educator in photography. Ingrid Pollard has a profound impact on younger generations of artists and thinkers.”

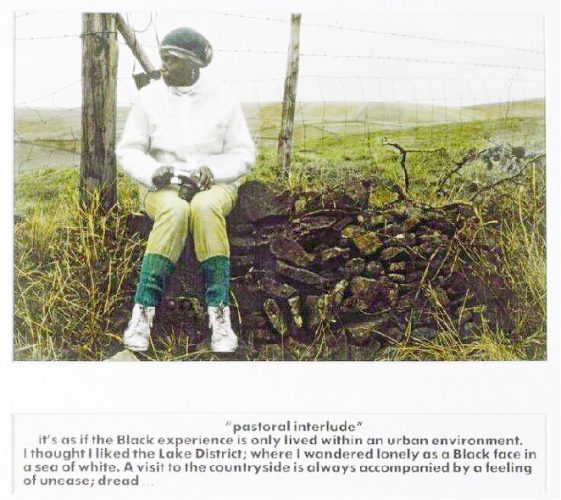

Pastoral Interlude

Pastoral Interlude from 1988 is perhaps Pollard’s most familiar and referred-to work from her oeuvre. The series of five images depict solitary black bodies that are typically associated with urban congestion or agrarian toil, wandering, attempting leisure, but made uncomfortable in the English rural landscape. Each image is accompanied by text that heightens the dissonance of these particular bodies within these spaces that are typically associated with whiteness and recalls histories that are buried and erased through wilful collective amnesia.

In the image from the series accompanying this article, Pollard photographs a friend whose unease emanates through the lens of her camera. The photograph’s subject does not directly engage the viewer. She sits before us to be viewed and surveyed. But looking feels intrusive. Her knees are clenched assuming a posture of resistance while her feet seem relaxed and set to move. Her shoulders hunch forward slightly, in a subtle gesture of enclosing and protecting her body. In her lap, she holds a camera, an object to better see with, but what she sees her camera does not. Instead, Pollard’s camera forecasts unpleasantness through the protagonist’s penetrating glance to her right. Compounding the unease, she sits in front of a wire fence that recalls exclusion, confinement, restrictions, and boundaries. Text beneath the image tells us, “[…] A visit to the countryside is always accompanied by a feeling of unease; dread, …” One wonders whether it is the countryside or living within these particular bodies that brings unease and dread.

At another register of reading, Pollard’s work in this series reflects notions related to cultural geography which in part explores the intersection between place and identity formation. Thus, Pollard’s figures who occupy space that is quintessentially English and their apparent discomfort communicated through their bodies and/or the accompanying text brings into question their identity and belongingness to the British nation space. For instance, in another work from the series, our aforementioned subject stands surveying a sublime landscape of undulating hills with tree and shrubbery clusters. As she surveys the expanse of space and greenery, we recognise a barrier to her intimate interaction and knowing of the space – a low stone wall bars her advance.

Pollard’s use of text further displaces the images of the series from momentary captures of idyllic wanderings and time spent in the countryside. One such text states, “…Searching for sea-shells; waves lap my wellington boots carrying lost souls of brothers & sisters released over the ship side…” Thus, the uneasy presence of black bodies, immigrant bodies, and former colonial bodies in these spaces unearth forgotten bodies. They are the colonised, labour-imposed bodies and the bodies which hold traces of certain types of encounters that could not be spoken of. In a 2017 interview speaking about this seminal work, Pollard explained: “[…] it’s just talking about the construction of England and where black people are outside of urban areas. […] The fact that it is now 25 years old, the relevancy of that is still quite important. So, that relationship of black people outside of the urban areas – how do we place them in English history? Because we know black people have been in this country 600 years at least, in and out of urban areas. Because it’s just [before] the Industrial Revolution that the majority of the population of England were outside of urban areas. Black people would have been in those rural areas but that story is not being told at all.”

Pastoral Interlude and other works interrogating identity and Britishness positioned Pollard as a significant figure in the Black British art movement of the 1980s. In the 2023 King’s New Year’s Honours, Pollard was awarded an MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire) for her services to art. One year earlier, in 2022, Pollard was nominated for the Turner Prize. The prize is named for the English painter J M W Turner (1775-1851) who although popular during his lifetime was also controversial yet hugely influential on the changing trajectory of painting, and thus art history. Nominations are made by the public from exhibitions held in the year before the award. Pollard’s solo exhibition Carbon Slowly Turning at the MK Gallery although not a retrospective represented 40 years of her practice and garnered her a nomination. The works in the exhibition explored Britishness, race and sexuality. In 2019, she received a Paul Hamlyn Foundation Award which allowed her the “opportunity to experiment, scale and develop [her] photo-based work with ambition” and a BALTIC Artists Award which supports the making of new work. In 2016, Pollard was awarded an Honorary Fellowship from the Royal Photographic Society.

In addition to numerous group and solo exhibitions (including one in Barbados in 2009), Pollard has participated in numerous residencies, and taught at several UK institutions including Newcastle University; Kingston University, London; and Central Saint Martin, University of the Arts London.

As a child, Pollard lived on Hadfield Street, Georgetown before emigrating to the UK at the age of 4 in the company of her sister to join their parents. Although she cannot pinpoint when her interest in photography began, Pollard recalls as a child pouring over the family photo album with its images and text. She also recalls as a child drawing quite well and that her father also drew. At 14 her father gave her a Box Brownie camera and later a 35mm camera. After writing her ‘O’ and ‘A’ level examinations, Pollard worked odd jobs to support her self-directed development before eventually undertaking formal studies. Pollard earned a BA in Film and Video from the London College of Printing (LCP) in 1988, an MA in Photographic Studies from the University of Derby in 1995, and a PhD from the University of Westminster in 2016.