There was a golden epoch when Georgetown was honoured with the title of the Garden City of the Caribbean. Early in the last century, the City Fathers had engaged in a tree-planting exercise which complemented the fastidiously well-groomed capital. The principal thoroughfares and the avenues of the dual carriageway streets were each lined with a specific species of plant. Sadly, today, only Main Street (the location of State House), and Independence Park (commonly referred to as Parade Ground), with a smattering of matured Samaan trees still retain that nostalgic throwback appearance of yesteryear.

The Samaan tree species – scientific name Samanea saman – is native to Central and South America and can be found anywhere from Mexico to Brazil. In the Caribbean, the local name varies widely from island to island, including the Samaan, Coco Tamarind, French Tamarind, Rain tree, Monkey pod, Five o’clock tree, Algarrobo, and Guango. Samaan trees attain heights anywhere from 50’ to 80’, even 160’ in extreme cases, and are characteristically distinguished by a large umbrella-shaped crown, a canopy which can extend as much as 100’ in diameter. The tree, a member of the legume family, has a massive surface root system, does not require much maintenance, and enjoys life spans ranging between 80 to 100 years.

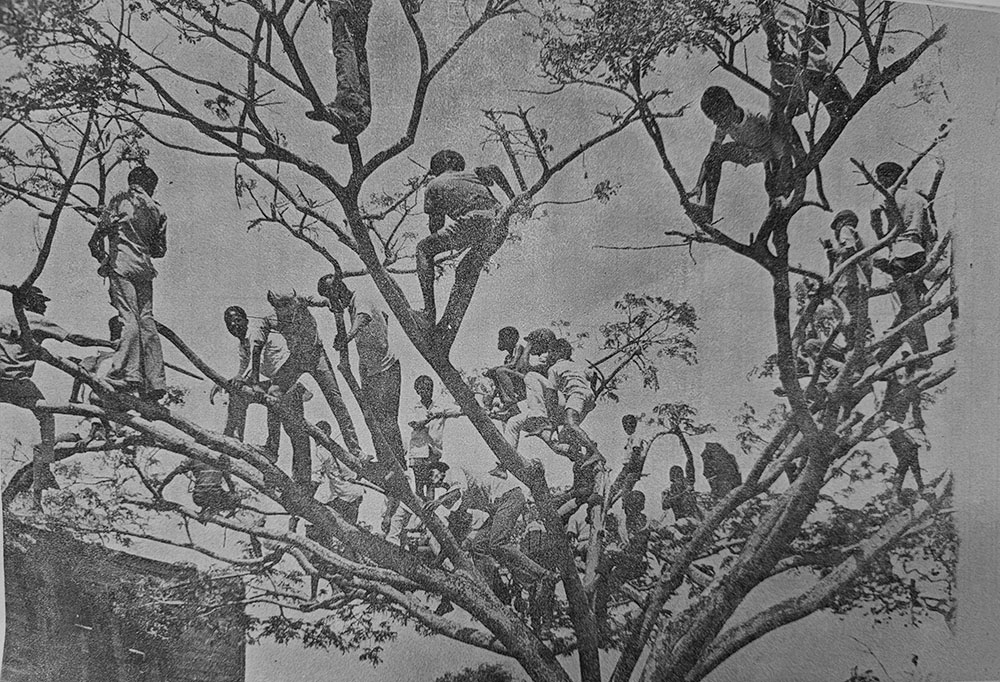

In the latter half of the last century, Test matches at the Georgetown Cricket Club – popularly referred to as ‘Bourda’, the city ward within which the ground is located – were always much more than a game of cricket. They were also unscripted operatic dramas, quite often unfolding in front of a packed house, with many of the occupants having joined the queues in the wee hours of the morn (on some occasions as early as 4:00 am), in order to secure one of the precious seats in the open air theatre. The stands engulfing the sward were often filled to capacity several hours before the scheduled start of play, and the colourful crowds entertained themselves with statistical arguments about the game, music, food and liquid refreshments, including varying strengths of alcohol. Many disappointed patrons who failed to gain entrance to the match, found themselves out of options. Some did the next best thing.

As Dave Martin sang in his calypso “It’s Traditional” (1975 Album ‘Sexy Lady’)

“… And if somebody put on a dance, or a big show or a movie

West Indians believe we have a duty to try and get in free,

We will scale the wall, climb the fence,

Buss up we hand and we knee

“Oh yes, Its Traditional,

It’s Traditional …”

At Bourda, this translated to: “We will climb the nearest tree, as long as it’s free, and we guarantee to see …”

Even before the stands were bursting at their seams, the bird men (also commonly referred to as bird watchers) had already established their positions in the Samaan trees overlooking the cricket ground. These avid cricket fans never bothered with the lines and simply ascended the trees, often barefoot with their ‘yachting’ boots slung around their necks. These adventurers, who did not suffer from acrophobia, were well aware of the risks involved in seeking a bird’s eye view of the proceedings or so one hopes. They sat, stood, or clung to their perches in nature’s readymade pavilion with its large branches and leafy shade. Having secured a prime spot, the well prepared birdman, remained in place, knowing fully well that any descent posed the possibility of the loss of his spot. Food supplies and a transistor radio were basic necessities for the experienced, with some climbers going as far as taking along a basket attached to a rope for purchases, and an umbrella for the unexpected – more often guaranteed – shower of rain.

Discerning the methodology of determining who got which limb on a tree, has so far proven futile. One suspects that with limited spots available, some sort of hierarchy or feudal system of fiefs existed with ‘landlords ‘ controlling prized real estate. The row of Samaans along the northern parapet of upper Regent Road was the favoured section since it was much closer to the ground – separated from the action by a trench and with a clear view over the one level stands of the day – as compared to those trees on the Merriman Mall which were more than double the distance away. Prime location was the vantage point in the trees nearest to the sight screen which commanded a line of sight often better than that enjoyed by the radio commentators.

One anecdote from the 1971 Test match between the West Indies and India recounted that a strapping gentleman arrived with a ladder (hitherto unknown) placed it against a favoured tree and declared that it was “a bob” (25 cents) to ascend. Some time after lunch, while everyone was fully engaged with action on the field of play, the budding entrepreneur and his ‘piece of capital equipment’ disappeared, literally and figuratively leaving his clients high and dry.

The most fearless climbers gained access to the much envied eyrie position of each tree, where one was rewarded a spectacular view of the field of play, and the coolest of breezes, amid the ceaseless segueing of the youngest branches. During the 1970s and 1980s, the unofficial title of best climber was claimed by a young man who had suffered from polio as child and was restricted to a wheelchair but often resorted to crawling around – more like scurrying – on his hands and knees (to which were attached custom made leather pads). Blessed with a well defined torso of developed shoulders and powerful arms, which compensated for his shrivelled legs, he could swiftly slither up to the apex of any tree from which he basked in clear views of the city’s tallest edifices of the time, including, St George’s Cathedral, the Bank of Guyana, Stabroek Market and the Pegasus Hotel.

Whilst adding colour to the theatrical production, the birdmen kept the disappointed patrons, curious passersby and the less adventurous standing under the canopies, updated with live commentaries, often sprinkled with vocabulary not conducive for public broadcast on either of the two radio stations of the day, Radio Demerara or the Guyana Broadcasting Service. Venturing up the Samaans came with two potential hazards for the local thrillseekers. The surface area on Regent Road was limited and could not facilitate the development of the extensive root system required to support the trees, and thus, they were somewhat stunted, and susceptible to collapsing under the burden imposed by the birdmen. During the decade preceding the 1974 visit of the MCC, five Samaans had crashed to the ground, injuring birdmen and damaging parked cars on two occasions. Par for the course were birdmen sustaining broken legs and/or arms when brittle branches snapped under their weight leading to an unwarranted descent.

Confronted with these disasters, the Mayor and City Council considered applying the law which makes climbing the council’s trees an illegal act under the Summary Jurisdiction (Offences) Ordinance, Chapter 14, soliciting the services of the Guyana Fire Service to use high powered water hoses to flush out the pathfinders, and even ringing the girth of the Samaans with barbed wire. These all failed; illegal occupation of the trees was virtually impossible to prevent. The council duly informed car owners and injured birdmen who sought compensation for loss and injury suffered during the collapse of Samaan trees, that it was not prepared to bear their financial burden.

Threat to the birdmen’s habitat

The threat to the birdmen’s privileged habitat arrived in the same format that confronts all manner of animal and plant life; progress. The necessity to expand the seating at Bourda saw the arrival of new double decker stands, which blocked the previously prized sightlines afforded by the Samaans. The first such development was the Clive Lloyd Stand, backing New Garden Street (the western side of the ground) in 1983, which had no bearing on the birdmen since there were no trees along that side. This structure was followed by the Shell Stand at the north-west corner (New Garden Street and North Road), which partially blocked the view from some of the trees on the Merriman Mall. Finally, came the Lance Gibbs Stand which backed onto North Road, blocking more trees on the mall. (The completion of these three stands completed the extinction of the former north-west stand.)

Alas, these wooden structures eventually had to be pulled down due to safety issues resulting from years of wear and tear.

The arrival of live television broadcasting of Test matches (In Search of West Indies Cricket – The Origin of Live Televised Cricket from the West Indies, 5 November, 2023) at Bourda dealt another blow to the birdmen’s habitat. In 1991, new media centres were built at both ends of the wicket. The two-storey buildings completely eliminated the highly sought sightlines from the north and the south ends. The death knell was sounded in the early 2000s when the Rohan Kanhai Stand (formerly South Stand A, located between the Ladies Pavilion and the southern sightscreen) was rebuilt as a two-storey steel structure with private boxes on the upper flat.

The last sentinels

Today, the depleted orchard of Samaan trees still stand amid the stumps of their predecessors, on the Merriman Mall, Vlissengen Road and upper Regent Road, safeguarding the moat which encompasses the GCC and the Georgetown Football Club against the inevitable passage of time. The massive trunks, battered and twisted are anchored by gigantic roots crawling as far as the drip lines of the canopy. Large branches snapped off by the combined pummelling of nature’s forces lie rotting close nearby; the gnarled bark protecting the hallowed landmarks from the whims and fancies of destructive human elements.

No longer do the alternating thunderous roars of approval and swooning wails of disappointment, synonymous with a Bourda Test match emanate from the field. No longer do the echoes of the unique sound of willow on leather die among the stout branches, leaves and pods of the Samaan. Their silent memories of Test matches past, are unspoken by the leaves to the many passersby, eluding those tired and lost souls who squat beneath the shade of the extended canopies during the blazing midday heat. Other meanderers, content to reflect under the glare of a full moon filtering through the dense canopy, can only imagine appeals for LBW, and the thunderous applause of another time. The stout unmounted branches, now glistening with moss, no longer bear the weight of a boisterous bunch of adventurers.

Former birdmen, now in their westering days, might pause to admire their former sanctuaries, recount stories of Test matches past, and smile at the memories of the good times in the Samaan Pavilions of Bourda.