The ancient township of New Amsterdam in Berbice has still managed to resist the hurly-burly of modern development and retain quite a feel of its long existence as an old urban district with an old world, if not colonial, atmosphere. Yet, surprisingly, it has retained virtually nothing in terms of visible signposts to remind anyone that it was the producer and home of many of Guyana’s most important writers, such as Edgar Mittelholzer (1909 – 1965).

The ancient township of New Amsterdam in Berbice has still managed to resist the hurly-burly of modern development and retain quite a feel of its long existence as an old urban district with an old world, if not colonial, atmosphere. Yet, surprisingly, it has retained virtually nothing in terms of visible signposts to remind anyone that it was the producer and home of many of Guyana’s most important writers, such as Edgar Mittelholzer (1909 – 1965).

Nothing remains but a plot of land on Coburg Street, neatly fenced, but quite vacant, where the house in which he once lived used to stand. It has long since been demolished. The only other landmark still extant is a house on North Road in Queenstown, New Amsterdam, where relatives who still live there say he spent much time and in which there was a four-poster bed on which he used to sleep. Interestingly, the house retains all its old architectural features.

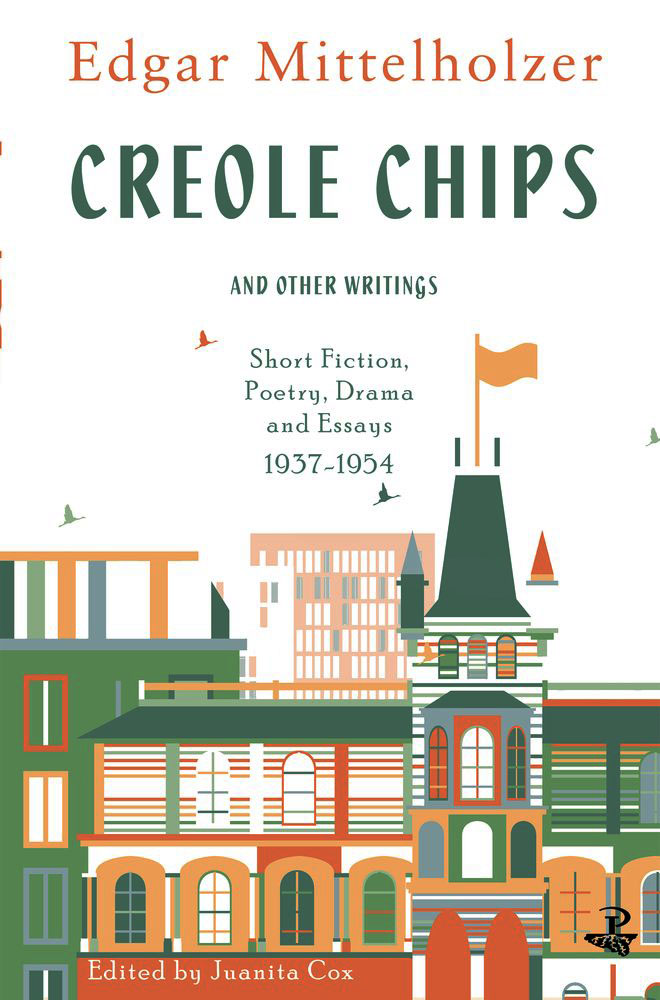

However, there is access to the best memories of Mittelholzer, of New Amsterdam and even of George-town, in the 1930s when he lived there, in his early writings. We can refer specifically to his first collection – the self published group of short skits titled Creole Chips (1937) that, according to legend, he used to walk around the town selling copies from door to door. It is a mark of his lifelong determination to be a professional writer and to earn a living from his publications.

However, there is access to the best memories of Mittelholzer, of New Amsterdam and even of George-town, in the 1930s when he lived there, in his early writings. We can refer specifically to his first collection – the self published group of short skits titled Creole Chips (1937) that, according to legend, he used to walk around the town selling copies from door to door. It is a mark of his lifelong determination to be a professional writer and to earn a living from his publications.

We are indebted to the substantial collection of his early work Creole Chips and Other Writings (2018 ) compiled and edited by Juanita Cox and published by Peepal Tree Press. Cox, the leading scholar on Mittelholzer, explains that “the prolific Guyanese writer . . . is best known for his many novels, all of which were published with the notable exception of Corentyne Thunder (1941) between 1950 and 1965. Several of his early novels received international acclaim and were translated into European languages including Dutch, French. Italian and German. Less well known among today’s readers is the range and scope of Mittelholzer’s shorter works . . . over 20 short stories, poems, and plays as well as non-fictional essays and personal writings. . . . No attempt has been made, until now, to bring this body of work together as one collection”.

Here are samples of the author’s very first published prose taken from Cox‘s 2018 volume.

CREOLE CHIP N0. 4

A paw-paw tree in Mrs Jones’ yard was leaning well over the fence and dropping dead leaves and (when rain fell) long trickles of water over the delicate limbs of a rose plant in Mrs Smith’s yard. Mrs Smith, who weas very proud of her rose-plants and extremely painstaking over them, wrote a friendly little note to Mrs Jones. The note read: “Dear Mrs Jones, I hope I’m not worrying you too much, but won’t you try to get that paw-paw tree cut down? It keeps dropping leaves and water on my Marshall-Neil rose-plant, and I notice it’s only a male paw-paw tree and doesn’t bear. I trust you are well. Yours kindly, Maisie Smith”

Mrs Jones, on reading this, made an acid sound and crumpled up the note, telling the bedpost that she would see Mrs Smith between the hinges before cutting down her paw-paw tree. “A male paw-paw tree is it? Wel just for that reason it’ll remain where it is. Confound her Marshall Neil rose-plant!” so taking writing-pad and pen, Mrs Jones wrote back to Mrs Smith as follows:

“Dear Mrs Smith. I think you are quite right about the paw-paw tree, my dear. It really seems so useless. I’m terribly sorry if it has damaged your Marshall Neil rose-plant in any way. I’m going to see and have it cut down as soon as I can”.

Of course, the paw-paw tree has not been cut down. It still leans over the fence. But it no more drops leaves or water on Mrs Smith Marshall Neil rose-plant, because Mrs Smith’s Marshal Neil rose-plant died two months ago.

CREOLE CHIP NO. 5

One bright morning in February last, Sergeant Strypes of Alfredtown Police Station said to Constable Batton that word had come to him that P-c Batton was in the habit, while on night-beat, of calling in at the cottages of various young ladies of doubtful repute. This was a serious matter, Sergeant Strypes pointed out, and if the truth of it could be proved it would mean instant dismissal for P-c Batton. Wilful neglect of duty while on beat! Did P-c Batton realise what this meant? Ha!

p-c Batton strenuously denied the charge, and Sergeant Strypes, with an ominous wave of the hand, said “Awright, awright” and told P-c Batton to go. Two days later P-c Batton was allotted the nine to midnight beat in Regent Street. At ten-fifteen P-c Batton, with a sharp glance up and down the deserted street, made his way bravely into a yard and knocked on the door of a small two-roomed cottage. A voice from within the cottage said, “Who dah?” the voice of Matilda Lesperance, the housemaid of Mrs Jeeves of Camp Street.

P-c Batton replied “Is me Charlie. Open the door, man. Is wha wrong wid you?”

The door opened to reveal Matilda and a kerosene lamp. Matilda expressed pleasure at seeing P-c Batton and told him to “Come in, sweetie. Ah didn’t know was you”.

P-c Batton entered, but before the door could be closed again a voice from Outer Darkness rapped: “Hold there, Batton!” it was the voice of Sergeant Strypes – Sergeant Strypes disguised as a ragged mendicant. The Sergeant was accompanied by Sub-Inspector Nancy, also disguised as a ragged mendicant.

CREOLE CHIP NO. 9

Soon after Cousin John had arrived back from Nickerie, the residents of St Anns Street, New Amsterdam, began to hear strange wailing sounds proceeding from the residence of the Benjamins. These sounds only made themselves heard in the still of the night, and the neighbours wagged their heads and told each other that they “thought so”. “Ha! That man, eh? They had always known that he dealt with bacoos. This proved it beyond doubt. Good gracious! Hear how the thing wailed at nights! The evil in this world, eh? And he a professing Christian.

Mrs Singer was of the opinion that he didn’t feed it on raw beef: that was why it wailed.

But Mrs Tawker thought it was because it had got out of his control. “Ha! You can’t go dabbling in the dark and get off scot-free, my dear.”

Mrs Whistknot held the theory that he kept it in the kitchen and the rats disturbed it. “You have to know how to treat these creatures”, she said wisely. You can’t make fun with them. Huh!”

Two days later the Benjamins’ cook had received a livid brand on her bare arm. Who had branded her? Nobody knew.

But Mrs Singer said to Mrs Tawker: “Ha! You see that, my dear. What did I tell you? I knew it was coming. I knew. Ha! You can’t play with bacoo and get off”. from Edgar Mittelholzer, Creole Chips.