Introduction

The Official Gazette of 11 May 2023 published two documents – a Guarantee and Indemnity Agreement dated 9th June 2023 (GIA) and a Contract of Insurance effective 1st. February 2024. The first deals with the Environmental Obligations of the three Contractors – Exxon, Hess and CNOOC – and the second, with third party insurance taken out by the companies to protect against a range of risks to their assets and operations. The beneficiary under the GIA is the Environmental Protection Agency while the beneficiary under the Contract of Insurance is the oil companies themselves.

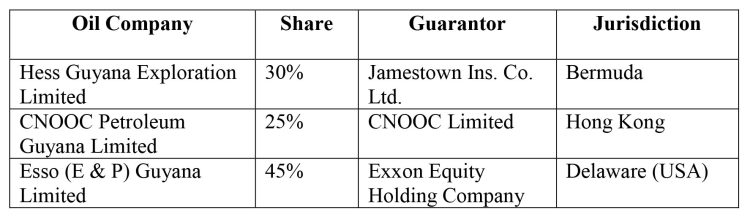

The 39-page GIA is made up of three separate but identical Agreements in which the Guarantors – all affiliates of the oil companies – undertake on behalf of the three Contractors to indemnify the EPA as the beneficiary on behalf of the Guyana Government.

Here is a table of the respective GIAs.

G$2 BN not adequate

The maximum total sum payable under the three GIA is US$2 Bn., less than bird feed in relation to the average US$15 Bn. cost of the last five international environmental disasters. Given the number of wells in simultaneous production in relatively close proximity to each other in the Stabroek Block, the risk of things going wrong increases exponentially.

The 2016 Agreement repeats identically the Indemnity provision of the 1999 Agreement, which was already overgenerous to the oil companies, on more than just royalty and taxation. If the GIAs are all the country can insist on in relation to environmental insurance, then Guyana is dangerously exposed. Any spill can spell disaster, wiping out the Natural Resource Fund in one stroke.

In every case, the GIA is guaranteed by an affiliate of the respective oil company. In identical wording, the three GIAs assure that the Guarantor is rated by an internationally recognised credit rating agency. It seems that the EPA forgot to ask the name of the credit rating agency, the actual rating. The lawyer representing the EPA should feel extremely uncomfortable about this omission.

In any case, it is doubtful whether the Agreements meet the requirement of the environmental permits which require Exxon as the Operator, to provide to the EPA legally binding undertakings of adequate financial resources for the Co-Venturers to pay or satisfy their respective environmental obligations regarding the Stabroek Block if their respective Co-venturers fail to do so. A total $2 BN for the three companies is far short of adequate.

The centrepiece of the Environmental Obligations is in respect of any pollution or other harm to the environment caused by petroleum operations in the Stabroek Block. These include the cost to prevent, reduce or contain the discharge or release of any contaminant; any monetary fine or penalty imposed by the government; and any damages arising from failure by the oil companies to comply with lawful directions given by the EPA.

Bearing the real burden

Drawing down from the GIA is not automatic and will probably be costly since the EPA will have to bear all legal costs incurred by it in enforcing or attempting to enforce the guarantee. To do so, it must first show that there has been a default; that the oil company has failed to discharge its environmental obligation; that the amount does not exceed the sum guaranteed in respect of that oil company; and that the EPA intends to draw down under the Agreement. In strict legal language, the Agreement provides that the Guarantor shall have no liability for any indirect, special, consequential loss, loss of profit or punitive damages arising from or relating to the guarantee and Indemnity Agreement, or the transactions contemplated. The consequences of these exceptions fall squarely on the country.

Suspicion

It is rare for finance companies operating in three different jurisdictions to have identically worded legal documents, or to have a choice of law in favour of a developing country with only a partially developed legal system. What is unprecedented is to have each of these three Agreements signed on the same day, across three different time zones, in which one signatory is common – that of the EPA head. It is unclear what legal advice the EPA took in negotiating and signing these complex documents, or why the Agreements have no subscribing witnesses, or why all the pages are not initialed as good practice requires.

There is a sneaking suspicion that these Agreements were put together with an eye on the case brought by citizens seeking to have such an agreement produced in court. The three companies have been evasive along the way, as the matter wended its way to the CCJ. Courts look with disfavour at such conduct. Something seems wrong that Exxon Guyana is now a major user of an expensive, overburdened court system to which it contributes nothing and extracts every drop of blood and ounce of flesh. Oh, and to have a state agency pay the cost of publishing their documents!

In a column on Wednesday of this week, I will compare the Guarantee and Indemnity Agreement under the environmental laws with the 2016 Agreement.