1966.

2024.

History is beckoning. We are in a season for reflections. A season for considerations of the paths travelled and reckoning with the potholes and the speed bumps that stymied progress. We are in a season to celebrate our achievements.

Celebrate we must.

Reflect we must.

Self-diagnose we should.

1966 to 2024. History requires a reckoning with our individual and collective politics and our politicians – who did what to whom in the past and how today, the children and grandchildren navigate the unfortunate repercussions. In this season, the actions of the present and their impact on the future of today’s and tomorrow’s children should be foremost in our thoughts. But alas, when it is deemed acceptable that an adult may work for $4,000 per day my hope dissipates for the actions of today precipitating the present and future we all deserve.

I lean on Lady Guyana. I think of the mosaic of her family – those she spawned and those she adopted and their unfortunate socio-cultural and socio-political offsprings. I think of Lady Guyana, and I want to believe that she would like to be a beacon in the Western world’s continued exploration with the complex repercussions of the plantations. With the rich and varied histories of those she spawned along with those she adopted, their belongingness to her (albeit forced in some instances), I ask what future can be forged that allows for a new people, seamlessly assembled like the homogenous seeming mashed potatoes with mashed turning plantain and mashed sweet potato?

I think of a certain Russian writer, a decaying corpse long before Lady Guyana became a Lady through acquisition of her independence. As a consequence of our season, celebrating the removal of one colonial force, I regret I must lean on his ideas in thinking about my perennial question; What should art aspire to? According to this celebrated writer, art should aim to unify people. In his lengthy essay ‘What is Art’, our writer distinguishes between counterfeit and real art. The latter can be distinguished from the former because of its infectious quality. Real art he claims “infects” people with the emotions of the artist.

To begin with, our unnamed writer asserts that art, as a human activity, does not exist for its own sake. Therefore, no to ‘art for art’s sake.’ He pronounces no to art existing to simply be, to be beautiful. Instead, art should be in service to humanity and its value determined by how beneficial or harmful it is. But before we veer off the path or fly over a speed bump politically instrumentalising art to assign it a use value, our writer deems the objective of artmaking to be the transmission of sincerely felt emotion to another. In other words, infecting others in like manner – causing others to feel as you felt – and thus unifying one with others.

Furthermore, the infection of one by another must be deliberate; a yawn causing another to yawn is not art or laughter causing another to laugh is not art. But through deliberate external actions causing one to feel pleasure or sadness as one feels, one creates art. Thus, art is the deliberate and intentional act of bringing individuals into union with one another, through shared feelings.

Additionally, art, according to our writer, should aspire to universality. In being infectious, art should aim to transcend social class and other barriers. Thus, in being both infectious and universal, art can bring disparate individuals, separated by ‘race’, class, sex, gender, nationality, into union with each other

Scenes of Long Ago

‘Scenes of Long Ago’ is a collaborative exhibition held by septuagenarian artist Jerry Barry at the National Gallery of Art Castellani House. Barry holds several tertiary-level qualifications including a Master of Fine Art from the University of Hartford, Connecticut, USA. Barry has participated in several exhibitions in the USA where he resided for many years. He last exhibited in Guyana in 2006. Barry’s current exhibition which opened to the public on May 18 runs until June 14, 2024, and occupies both the ground and first floors of the gallery.

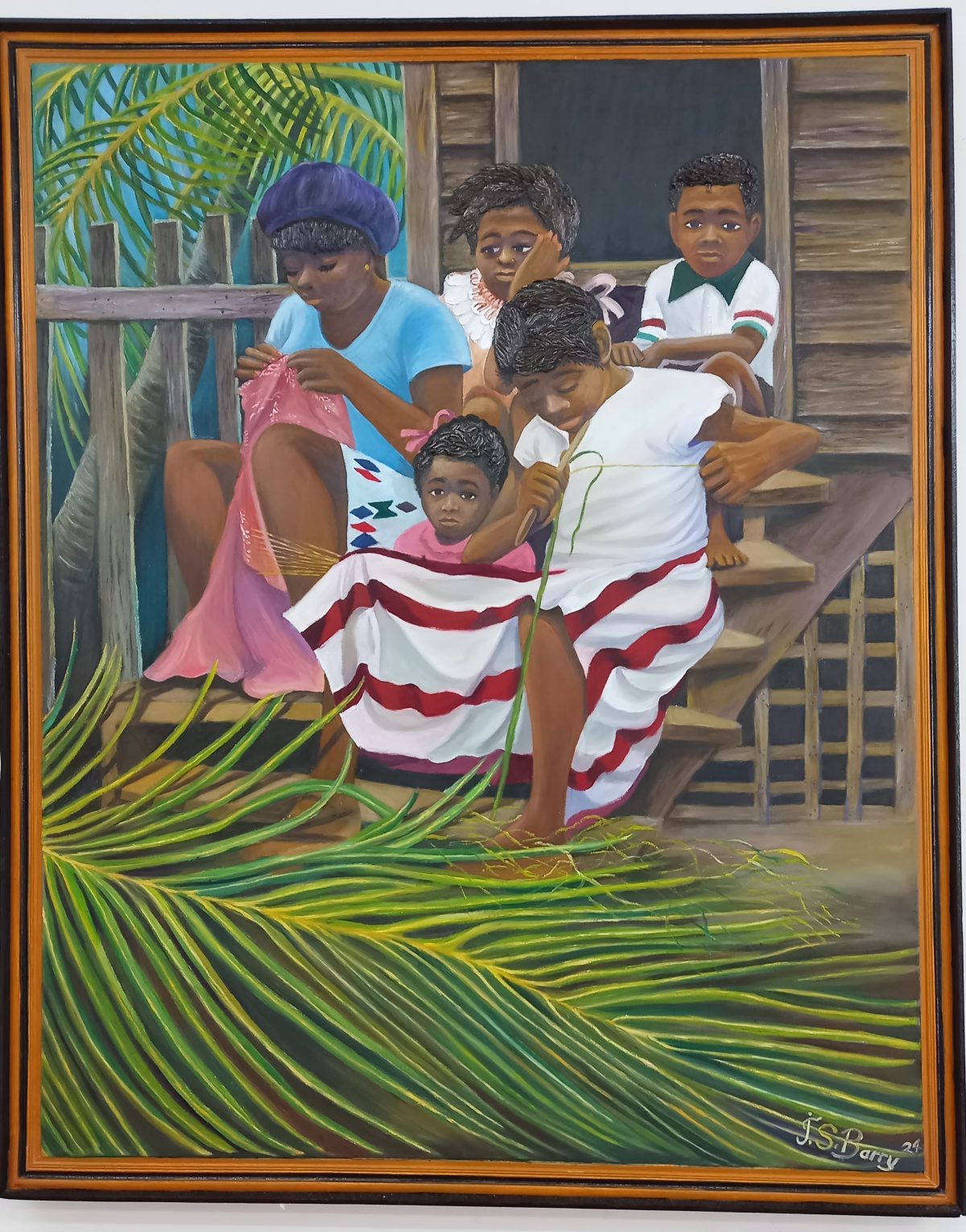

Nostalgia is the feeling of infection in ‘Scenes of Long Ago’. Differing from the fast-paced building boom of contemporary Guyana, Barry’s canvases offer glimpses of yesteryear that propose a tranquil, clean, luscious Lady Guyana characterised by simple industry. Donkey carts traverse the city street in the foreground of the Stabroek Market clock tower and the East Coast Village of Nabaclis. A mother (presumably) sits on a step mending a garment with well-dressed children frowning beside her. One senses that perhaps their play has been curtailed. Barry’s title, “Sunday Morning Chores” reinforces the feeling of disappointment the children appear to feel. And indeed, one of the four children in a crisp white top and a red and white skirt strips a palm branch with her face not quickly seen by the mom should she glance her way. In other canvases, the streets are empty. No children playing. No half-clad men walking with cutlasses or sticks as can be seen today in the city and our villages. No signs of drug addiction or abuse. One feels the peace and security of Barry’s yesteryear Lady Guyana.

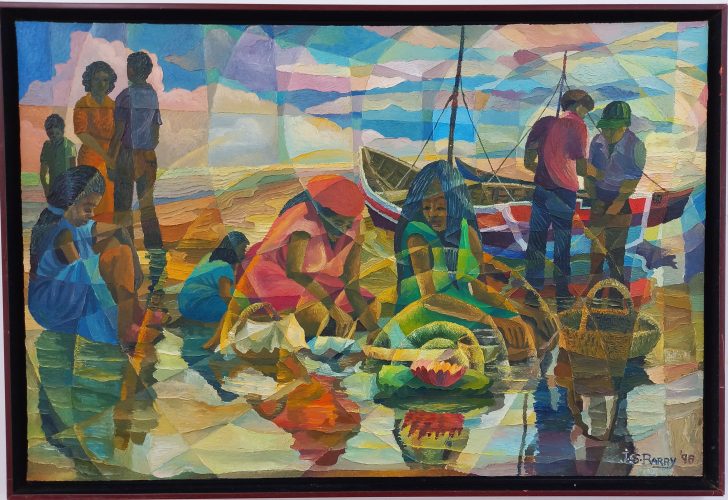

I wonder how much of Barry’s nostalgia-toned paintings are sanitised recollections or carefully articulated longings? But I am filled with similar longings. “Early Morning Prayers”. “Cleanliness is next to Godliness”. Tidy and colourfully dressed ladies set offerings in place as other well-dressed men and a woman stand nearby. One wonders whether the two men in conversation concern the boats in the background and whether the man and woman to the left of the composition are bonded as individuals may be. A peaceful world of prayer, business and perhaps courtship – none of the violence that has caused Lady Guyana to be high on the gender-based violence incidence rankings. I am moved with a longing for strife-free coexistence in all spheres of our life.

In Barry’s images, the houses are all modest wooden structures, well-painted. No sign of deterioration or neglect. No sign of nature reclaiming homes or yards at a pace that outpaces homeowners. No sign of vast disparities in socio-economic realities. No sign of the transformation of the city or the villages. I wonder how contemporary Guyana might look through the lens of an artist two or three decades from now.

Barry’s exhibition is without question worth visiting and revisiting.

Akima McPherson is an artist, art historian, and art educator.