By Nigel Westmaas

In Guyana, the evolution of policing has been deeply intertwined with its colonial history under British rule. The British initially relied on military units to maintain order in the colonies, but as the need for more structured control grew, formal police forces began to emerge in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The policing system in British India, established with the Indian Police Act of 1861, is one of the most notable examples of British colonial policing. It was designed to maintain public order and help the British control such a large population. The system was heavily militarised and centralised, reflecting a model of foreign control rather than community policing.

The Guyana Police Force was formally established on June 11, 1839, under the control of an inspector-general with “an ordinance to establish an effective system of police within British Guiana.” The duties of the police at the time were to “aid, assist and obey the magistrates and to bring to justice all persons charged with or suspected of murders, robberies, thefts of all description, and misdemeanours, as well as all rogues, vagabonds, idle and disorderly persons, and to suppress and prevent all tumults, riots, brawls, outrages and disorders, and all other offences of any kind whatsoever.”

Early police formations

The British model of policing, as implemented in Guyana and other colonies, was characterised by a focus on control and coercion especially against the black population and this was indicative in the pre-police formation called the burgher militia which regulated slave society, followed by the dienaar—free people of colour with police powers who were restricted in the sense that they could not arrest white people. This model was not only about maintaining public order but also about asserting colonial authority, often at the expense of local populations.

Understanding the police force in Guyana requires grasping two critical aspects that reveal its historical nature and procedures. Historically, the force has shown a discernible anti-black bias. This bias, reinforced by institutional socialisation and values of power and control derived from the British colonial era, resulted in an authoritarian structure often at odds with the interests of the working class. Police officers, shaped by this structure and their training, tend to become socially isolated from the wider community, in essence black police socialised in anti-black repression. Historically, the police have collaborated with colonial and post-colonial authorities to suppress strikes, rebellions, and resistance from African and Indian Guyanese. Additionally, as the force evolved, it also repressed the “East Indian” community, particularly during uprisings on sugar estates where demands for justice and better working conditions were made, highlighting the systemic repressive nature of the police across various ethnic groups.

According to Joan Mars (2002), there were three general characteristics of policing in the colony: first, an emphasis on control and coercion as a primary function (as against service); second, the “legitimation of police behaviour, however reprehensible, by the executive and judiciary”; and third, the “indiscriminate resort to violence or ‘deadly force’ as a means of ‘social control and especially crowd control.’” These characteristics have persisted with some changes here and there, right into the post-colonial, independence period and beyond.

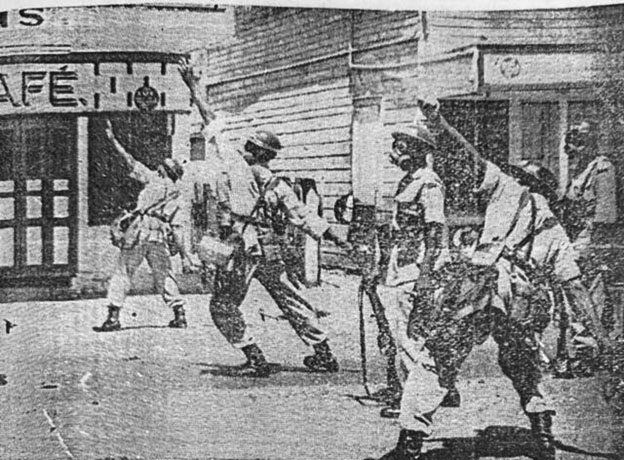

The implementation of a repressive outlook by the colonial police force was evident in the huge disturbances in the 19th and into the 20th century, including the 1856 disturbances in Georgetown, the 1889 riots, the 1905 uprising/riots and Indo-Guianese labour insurgencies against the colonial state and its labour and social regulations as evident in places like Skeldon, 1870, Rosehall 1913 and Enmore, 1948 among others. The Rosehall suppression of indentured labourers by the police was especially brutal. A police corporal, Ramsay, was killed along with 16 indentured labourers. It must be underscored that at the time the derogatory and offensive term “coolie” was widely employed in the press (and society) to describe the Indian population.

According to police historian William Orrett, the twentieth century “began with more strikes throughout the colony over wages, with assaults on overseers and drivers, but the police were able to prevent serious disorder.” Later, “800 Martini-Enfield .303 rifles and a Maxim gun of the same calibre were issued.” But Orrett was reporting from a law enforcement perspective. What he did not outline was the egregious use of force by the police in the 1905 riots.

The repressive Colonel Lushington and the case of Eliza Jones

Under the leadership of Major S Lushington (later Colonel), who was notorious for his role in suppressing the 1905 riots, the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) was established in 1903-1904 and marked a significant evolution in policing in Georgetown. Tasked with maintaining comprehensive criminal records, the CID aimed to “obtain full descriptions of all criminals, to keep in touch with their whereabouts through the force in general, maintain a new system of identification, and finally to keep up to date a special police map of Georgetown.” This development might have been prompted by the rise of the so-called “centipede” gangs that emerged in Georgetown.

By 1906, the department had recorded and classified 653 fingerprint records, 1,642 descriptive histories, and 341 facial diagrams. These facial diagrams were a precursor to the modern photographic identification systems used in law enforcement today. That year witnessed the establishment of the Police Mounted Branch. In response to social rebellions, 40 horses were purchased from the United States to equip this new unit, enhancing the police’s mobility and their capacity to manage public disturbances.

Colonel Lushington’s tenure, however, was also marked by controversy, particularly in the treatment of suspects. In 1906, he was involved in the pre-trial maltreatment of a murder suspect named Eliza Jones, an incident that highlighted the harsh methods sometimes employed by the police. Jones from Mahaica was charged with murder and sentenced to death. Colonel Lushington’s handling of her case, particularly his extreme pressure to elicit a confession, including forcing Jones to kiss the Bible, was criticised as “grave misconduct”. The case’s irregularities even caught the attention of the British Secretary of State for the Colonies. Due to the reliance on purely circumstantial evidence and the improper interrogation methods used by Lushington, Eliza Jones was eventually acquitted. The case was extensively covered by “The Creole,” a local black newspaper. The treatment meted out to Jones was consistent with the treatment of women in general and black women in particular. Shaving of the hair of women of African descent on release from prison was also a method of racialized social control, highlighting the deeply entrenched issues of discrimination and violence within the policing system.

The economic pressures of the early 1920s led to significant challenges for the police force. In January 1923, following a reduction in the civil service budget, the police force went on strike, as documented by ARF Webber (1931).

Further unrest occurred in January 1924 when police were involved in a deadly confrontation with citizens at the famous Ruimveldt labour uprising. During these disturbances, the police fired into a crowd that had thrown rocks at the mounted police, resulting in the shooting deaths of 13 people. This catastrophic event underscored the volatile relationship between the police and the community during periods of social and economic strain.

In August 1933, the Daily Chronicle reported a significant development at Police Headquarters, as women began working as operators for the newly installed telephone switchboard. This move marked a progressive step in gender roles within the workforce at that time.

In response to growing demands for better organisation and representation, a police federation was established in 1950. This body aimed to address various issues affecting police officers and improve their working conditions.

In 1953, policewomen were introduced into the force and the first woman enlisted was reportedly Dianne Cendrecourt.

Over time, the Guyana Police Force has tackled some of the most notorious criminals, particularly during the pre-independence period. Here, just four examples are highlighted. The first case followed the murder of a two-year-old white girl, Molly Schultz, in 1917. Schultz, the daughter of John Schultz of Booker McConnell, had her eyes gouged out and was squeezed to death in what was deemed an “obeah” ceremony. Her murder led to a thorough police investigation that resulted in the arrest of a group of residents of Nooitgedacht, West Bank Demerara. Eventually, six men—Sudin, Mahadeo, Jugdeo, Bakridi, Paul, and Lewis—were hanged in 1918 for the offence.

For some reason, 1959 was the year of the criminal. During this year, one criminal “Sotie” escaped a police dragnet but committed suicide. Edward Lashley, a notorious criminal with 64 convictions including the murder of a police officer was hanged in April for murder, and 5,000 people gathered outside the Georgetown jail to ‘hear’ the hanging. Another bandit, Clement Cuffy, was eventually caught and shot dead near Ruby, East Bank Essequibo after a massive manhunt involving 200 policemen, described as “the biggest manhunt in the annals of British Guiana crime.”

Ethnic imbalance and the Guyana Police Force

The issue of multi-racial composition of the Guyana police force representing the ethnic composition of the country has been raised time and again. John Campbell’s 1987 history of the police highlights the notable developments in 1885, where a significant number of East Indians were incorporated into the police force. According to the report, “out of 157 ranks enlisted that year, 58 of them being East Indian… ,” with many being “recommended by the Immigration Agent-General.” The inspector general emphasised to these Indian policemen that they must “arrest their own race as they would ‘black people.’” What unfolded in the subsequent century concerning the ethnic balance within the police force continues to be a debated topic in the sociology of Guyana. However, after the race riots of 1962, 1963, and 1964, the International Commission of Jurists (1965) recommended the introduction of “racial quotas” to mirror the ethnic demographics in the police force.

Indeed, the 1960s were marked by significant civil unrest, with riots calling for reforms in police methods and interactions with the community. These events tested the police force’s capacity to manage large-scale public disturbances and led to critical assessments of their procedures and force composition. For example, in the wake of the 1964 riots the New York Times reported that H J M Hubbard, Minister of Trade and Industry, who was at the emergency camp set up for Indo-Guianese refugees from Mackenzie on Georgetown’s outskirts, reported that police officials failed to “enforce discipline among their men and outrages against East Indians were reported.” There was also condemnation from the opposition PNC about the treatment of its activist, Immanuel Fairbairn who was tortured while in police custody in 1963.

The issue of ethnic imbalance in the forces (inclusive of the army) should also be viewed in light of the wider political economy and in relation to other sectors where disparities in ethnic equality and representation still persist.

After Guyana gained independence in 1966, its police force underwent modifications to align with the objectives and governance structures of the new nation. However, these changes did not constitute a “revolution,” as many pre-independence structures have persisted—some even to the present day.

In Guyana, policing strategies and law enforcement methods continue to be significantly influenced by political directives through the main political parties that have held state power since independence. These influences can impact how policies are implemented on the ground and the overall effectiveness of policing. It is crucial to consider these political contexts when evaluating the role of the police, as they can affect everything from resource allocation to operational priorities. For instance, the term “negro” is still employed in the formal police identification system to describe African Guyanese, despite the global civil rights movements and shifts in language since the late 1960s that led to the removal of outdated and racially offensive terms. This persistence of its usage means it survived two political administrations and highlights the need for public education and legislative action.

In a March 2023 Stabroek News column, Akola Thompson discussed the disproportionate use of facial recognition technology by the police, emphasising that in “the tracking of historically Black communities in Guyana, the GPF has created an environment of fear and instability among residents.” She argued that such biases contribute to a cycle where Black communities are disproportionately targeted by law enforcement, thereby reinforcing negative stereotypes about criminality within these groups. Walter Rodney articulated a related sentiment in the case of Jamaica in Groundings with my Brothers, stating, “Since ‘independence’, the Black police force of Jamaica have demonstrated they can be as savage in their approach to black brothers as the white police of New York, for ultimately they serve the same masters.”

The influence of the state in power on the practice of extrajudicial elements in police practice is evident in relatively recent history. During the Working People’s Alliance’s public political activity especially from1979 to 1982, a “death squad” emerged under the Burnham administration to suppress the organisation and the accompanying civil rebellion. In the early 2000s, organised police units known as the “phantom squad” and the “black clothes” police appeared under the Jagdeo administration. A consistent feature of their operations was the extrajudicial killings of numerous African Guyanese.

Recognizing these issues, ongoing efforts to modernise the Guyana Police Force must be introduced alongside the sensitising of the general force to racial and cultural issues, gendered violence, and other initiatives to improve community-police relations.

The goal of these substantive reforms would be to establish a more equitable, nonpartisan, and effective law enforcement system that serves all segments of Guyanese society fairly and competently. This includes not only combating crime at the grassroots level but also addressing white-collar crime and corruption at the upper echelons of society.