Akima McPherson: How does it feel to be back in Guyana exhibiting again?

Akima McPherson: How does it feel to be back in Guyana exhibiting again?

Jerry Barry: You can imagine, I’m very elated. It is something I had planned for a long time. I brought an exhibition in 2006 but it was a small introductory one. The response was huge. Busloads of kids visited. I was excited, but I said this is not the real show. I had to go back home and prepare. So, I went back to my studio.

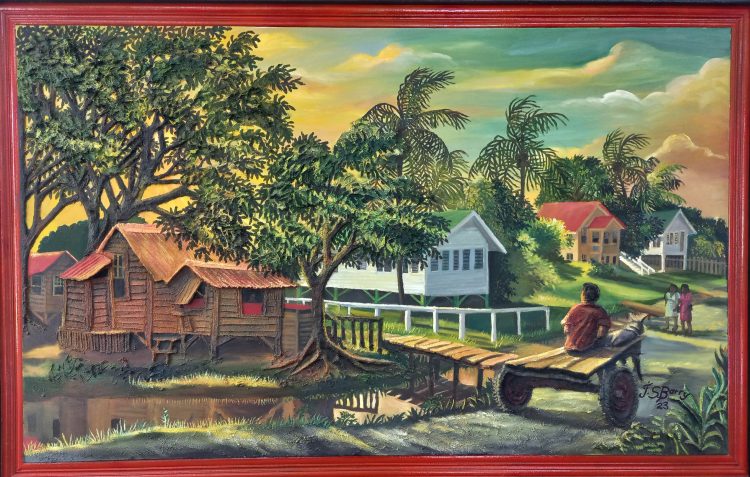

I didn’t bring many paintings. I painted most of them here. […] I used to have my friends and relatives send digital images of [Guyana] sunsets and sunrises but I felt I needed to be here, to experience the atmosphere.

AM: You have over 50 paintings in the show.

JB: 59. They are paintings and [a few] prints.

AM: How long are you here working on the collection?

JB: I’ve been here for over two years now. See, I wanted to come and get a feel of the colours, … the right colours. Like I said, if you want to do a true landscape you have to be [in it] to get the true atmosphere.

AM: Did you do the paintings en plein air (outdoors)?

JB: I worked in my studio. But I would use my phone to capture the scene. I like to go and experience the space before I paint.

AM: Since you are not working outdoors to capture the atmosphere but are indoors it means people are not seeing you work…other artists, for instance. How was that experience? It must have been very solitary.

JB: It would always be a solitary experience. I lived here. I used to sketch here. Before leaving for the States, I used to go around to the villages on foot or bicycle and make sketches. I’d do the sketches and return to the studio and paint. See, colour changes within the minute so I wouldn’t try to paint. Prior, I would try to jot down the colours [while] in the landscape then go home and work quickly before I forget the colours. So those paintings in the exhibition are from sketches of scenes I’d seen.

AM: When did you leave Guyana?

JB: I left in 1990. I used to come every two years or every year and I continued the same routine, going around to the villages making sketches. I have hundreds of these sketches. So, what I wanted to do was paint out my favourite ones for this show. But I had painted them three or four times already. So, I was doing the final rendition for those scenes. See, I like to experiment with ways of capturing mood.

I brought back four paintings. One is “Kissing Bridge with the Bamboo Patch”. “Breadfruit Tree in the Moonlight” is another. […] I used to study moonlight. I was a colourist but I was not necessarily studying the [colours in the] scene but the atmosphere of the moonlight. For instance, how the atmosphere is with the dew. I wanted to get at that feeling.

AM: So, you were really trying to capture mood?

JB: Yes, capture mood and that is tough. I paint here and many of my trainees and mentees would look at the work and say it is finished and I would say no. […] I haven’t captured the mood.

[For many painters], the foundation is [the basis to] begin to paint. That underpainting that they do, I do it differently. I would do layers and layers of paint as I try to capture the mood of the painting. Only when I’ve got it can the painting begin.

AM: I understand what you are saying about mood. When I was training as an undergrad we were left to paint and then someone decided to teach the lot of us how to prepare the ground. It felt like all we were doing was trying to get enough paint coverage on the ground. Then when I actually went to paint, sometimes the energy of my application of the ground didn’t match the energy of the painting that was ultimately intended. Now when I paint I am thinking about mood from the beginning and that determines my application of paint.

JB: Well, different schools and persons have their own approaches. Sealing the canvas so you can begin to paint is what most art schools teach. I believe that from A1 you begin with capturing the mood … until I’m satisfied with what I’m seeing the painting never starts. But when you look at it, it may look finished but it is not. Then I will bring in the light and that will determine what will happen next. You bring in the light, then the dark, then you bring the light in again and it is a sort of see-saw between the two. You keep doing that until the painting says I have had enough.

I think the painting controls … its own destiny. If you approach painting from within the painting it will tell you where it wants to go.

Barry described a painting that he could not complete in time for the show. It depicts a young girl on the seawall with her baby and other children as she watches men repair boats. He described her relation to the light – the sun. It is clear that the figure is not paramount but the figure’s relationship to the rising sun is. I need to see the painting because my thoughts are wandering: how old is the girl with the baby? What is her relationship to any one of the men at work? I’m distracted by thoughts of parenting in circumstances of dire pecuniary limits and potential parental irresponsibility. I interrupt my thoughts to say,

AM: Your watercolours are wonderful and I think they wonderfully capture mood.

JB: Yes, especially with watercolour, it is 90% mood. For me, if you go for just the academic approach it flattens out the painting, but if you paint strictly on the basis of mood it’s fantastic.

Barry mentioned a painting with boats. He discussed his theory of the third eye. It is not the Third Eye of the Chakra system but a theory that determines how he composes his pictures to allow the viewer to feel within the space. I reflected on his images and recalled this effect. He marries sculpture with painting so there are evident sculptural effects in his oil paintings. “Sunrise at Nabaclis,” he pointed out, is a good example of this marriage. He shared some unexpected techniques alongside mentioning the anticipated palette knife. He explained how he uses thinned acrylic paint like watercolour. He explained that by using acrylic in this manner, colours do not bleed. We discuss bleeding colours, watercolour paper, and his approximation that his painting of a Croton has about 75 layers of (as he terms it) “acrylic watercolour” – acrylic thinned and used like watercolour.

AM: So, despite being a septuagenarian you are always experimenting?

JB: Oh, yes! Learning is a lifelong experience. As soon as an artist stops learning, stops experimenting, they are going to fade out.

[…]

Jerry Barry will host an Artist Talk on June 12th at the National Gallery of Art, Castellani House.