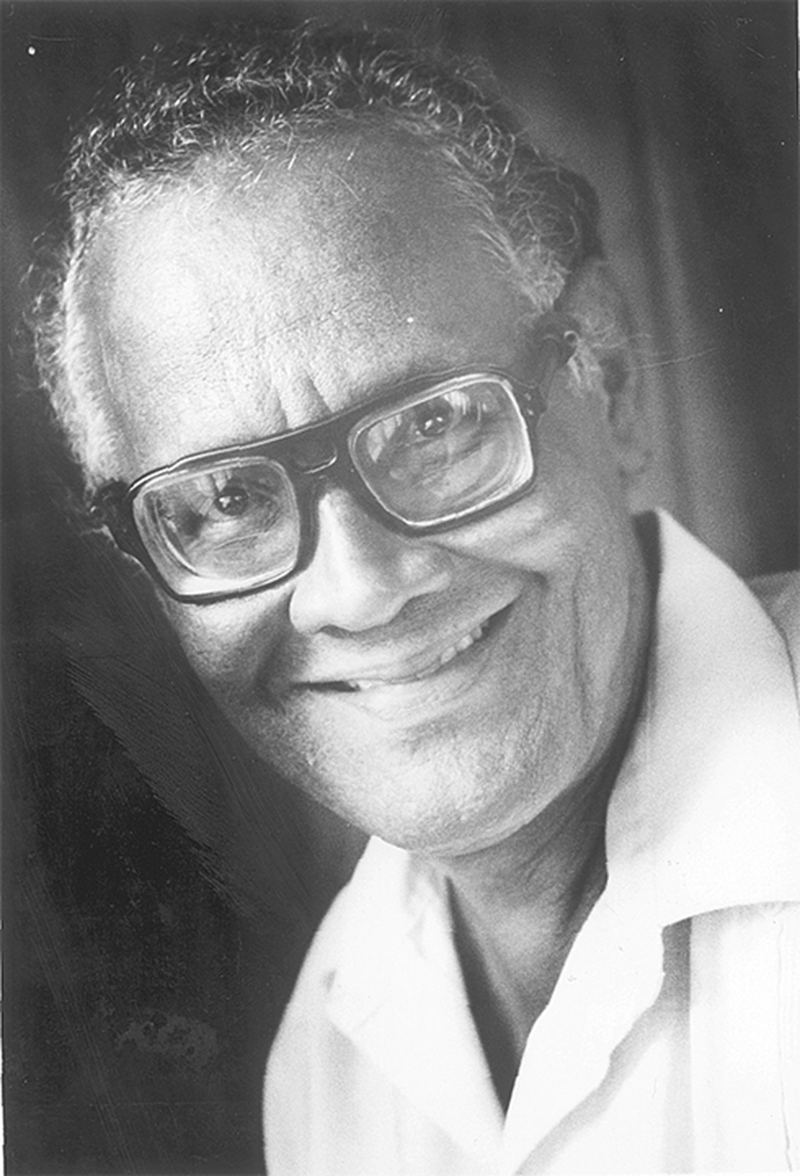

Every year around this time, we honour the extraordinary Caribbean poet Martin Carter, who was born in June. We do so this year with a revisit of significant but not so well known selections of his poetry and prose.

Every year around this time, we honour the extraordinary Caribbean poet Martin Carter, who was born in June. We do so this year with a revisit of significant but not so well known selections of his poetry and prose.

In June 2000, there were two important publications: All Are Involved: The Art of Martin Carter, edited by Stewart Brown, published in the UK by Peepal Tree Press and launched in Guyana during the Annual West Indian Literature Conference hosted by the University of Guyana, and a special double issue of the journal Kyk-Over-Al 49/50: Martin Carter Tribute, edited by Ian McDonald and Vanda Radzik.

Brown collected new and existing learned articles on the art of Martin Carter, making scholarship on this foremost writer easily accessible for the first time in one volume and enlarging his international recognition. Kyk-Over-Al released the special tribute with an abounding variety of contributions, poems, tributes and criticism. There were also samples of Carter’s own work – selections of his prose, which is far less known than his poems, and a rare treat – a few recently discovered poems that were never previously published.

These are worth reprinting because they are such rare treasures, and because of what they can reveal about Carter’s preoccupations, things never before publicly analysed. The three poems here were published for the first time in this issue of Kyk-Over-Al. They are part of a suite of five poems along with two handwritten manuscripts and a poem “For the Students of St Rose’s”.

Poem No 2 in the suite, for instance, is an excellent example of Carter’s metaphysical verse. Kamau Brathwaite is known to have commented on this poet’s excursions into the metaphysical, particularly in “I Am No Soldier”, cautioning that there were too many echoes of John Donne and the seventeenth century English, and that the imagery was alien to the Caribbean. Carter was, in fact, referring to the surroundings at the place where he was imprisoned in 1953 and comparing it to the vast, endless regions of emptiness, loneliness and the stark unfriendly severity of an arctic night, referencing not only physical discomfort, but a sense of isolation and over all, solidarity with fellow combatants of struggle wherever they may be across the wide world.

In this poem reproduced here, he references the vast, endless vacancy of the sky, relating it to other boundaryless stretches like the sea and loneliness. These images of the overarching sky, bent to match the shape of the earth, are not unknown to other Carter poems such as “Bent”. He places himself in confrontation of space and the need of a compass to navigate it. He uses metaphysics to negotiate human compassion.

The metaphor of the bat appears in poem No 3, as it does in another suite of Four Poems and “Demerara Nigger”, waking up and flying at night to “confuse clocks”, hanging on rafters and “plunging into depths that are always dark”. The poem’s syntax and cadence are as precise as is often the case in Carter’s careful craft.

In his little known poems, like the one dedicated to St Rose’s High School in Guyana is another example of this craft. At the time when the poem was written (1974) St Rose’s was a girls’ school and Carter plays on the uniform worn by the students, using it as a central metaphor for the whole poem. The white socks, the colour green and its relation to nature are all at the core of the poem and its relation to freedom as opposed to imprisonment.

The prose pieces were selected by Nigel Westmaas for Kyk-Over-Al and can reflect important elements of Carter’s work and development that take us well beyond the poetry with which most readers of Carter would be familiar. They are not so familiar with the prose. “Pablo Neruda” was first published as an editorial for the magazine Thunder, Vol 5: No 42, January 15, 1955. Thunder is an organ for the PPP and Carter worked with it for some time in the 1950s and for a period, served as editor, a position he took over from Janet Jagan at that time.

The periodical was a very frequent publisher of poetry as well as reviews, film, the arts and literature. Carter’s own poetry was first published there. He was a very prolific writer of prose contributions to Thunder, including, of course, several editorials. After that early period of his development he is known for many other important prose pieces, including a convocation address at the University of Guyana, where he also worked as Artist In Residence and then Senior Research Fellow.

One of his duties at the university was to run the courses in Creative Writing, and it is not surprising that he wrote theoretical pieces, including those on poetry. Many have been the attempts by poets throughout history to attempt to define poetry. Carter theorised here in “About Poetry”, which was first published in Kaie, July 14, 1976, the journal of the National History and Arts Council, which became the Department of Culture in Guyana.

2.

For thousands of miles the sky is all the same

Just like the sea or time or loneliness.

It was the heart that noticed all of this

When it computed distance into loss.

The sky bends with the earth and earth with space

And those who navigate are full of hope:

But the compass that they need is far more kind

Than love’s magnetic north pole of desire.

3.

I will walk across the floor through tables, through voices

like a man who is very drunk I will think only of the moment

Abolishing time’s furniture I will make myself my own

A high roof with rafters whereon I’ll hang like a bat.

Flitting through twilight by trees that are going to sleep

I will disappear into the flame of sunset by the rim of the sea:

Plunging myself into depths that are always dark

I will see all things and return to tell you all..

Using the speech of men I will whisper to you

Of dreams that change to ghosts and haunt a life;

And prayers in the heart that mutilate

I will repeat, until your eyes are streaming.

For The Students of St Rose’s.

Green must come the wind; trees are clouds

And a bosomful of rain a clutch of tears.

But life is not a uniform; nor do the socks

of a hummingbird

fall down for a want of garters.

Every pavement is a hard salute

to a hand raised; the city a cell

and God a jail-bird. Hence

God lives in the prison of every human heart.

And for a green wind, a world waits.

About Poetry

From a particular position it seems more than ordinarily useful to think of poems as codes. Also since poets are conventionally lumped with other artists it is also to suggest that while the poet makes use of art in the organisation of his code or codes, he is not an artist in the same way, for instance, as a musician or a painter or a sculptor. Whitman in his preface to his Leaves of Grass said: “The poetic quality is not marshalled in rhyme or uniformity or abstract addresses to things nor in melancholy complaints or good precepts, but is the life of these and much else . . .”

Every time someone construes a true poem he makes one. He completes, as it were, the poet’s “breaking into the chain”. Every proper reading is also another kind of completion. But every proper reading is only as significant as the original code is significant; which is as much to say that the code itself is a true poem.

So what elevates a given code to the status of a true poem? To attempt an answer one must attempt an interpretation of a true code. If, as is advanced here, a code is something based on mutuality; something itself which provides the ground or the possibility of expression, then herein the code becomes a knack. A knack is the mutuality of simulability. Hence what follows.

Star code and tree fruit. Shout

in the throat of the music of my loss.

Rain. The nymph of a grasshopper

laughs. Flood surrounds the fence

of the heron’s knotted ankle. Cattle

man or beast of water, when I tried

I touched. When I touched

I found myself. The frail udder

of love waits for strong fingers’

this code of stars has been a long time waiting

and when my feet scuffle, the leaves of trees talk.

From Kaie, 1976

Pablo Neruda

On the back page of this issue is a poem by Pablo Neruda (“I want the Earth”). Pablo Neruda is one of the greatest living poets in the world. He is a Chilean and his poems are originally written in Spanish. The version printed here is therefore a translation.

Two years ago Pablo was awarded a Stalin Prize for outstanding work in the cause of the maintenance of world peace. The award of such a prize is a tribute to Neruda’s poetic power, a tribute to his unflinching stand in defence of human culture and civilisation. It is also a tribute to the Chilean people without whom there could be no Pablo Neruda.

In his early life the poet travelled widely in the world for he worked in the diplomatic service of Chile. He served from time to time in India, Burma and other Eastern and European countries. At the time he was still dominated by the anxieties of decaying bourgeois society and his poetry was permeated by death wishes and full of all the obscurantism now so fashionable in certain literary circles in Europe and America.

It was during his period of service in Spain that he really came alive. The Spanish Civil War opened his eyes to the truth. The inhuman activities of the Fascists assisted by Hitler and Mussolini revolted him. He saw how ordinary men and women could become heroes in the fight for liberty, how down there in the thoroughfares of reality that history was being made. And from then on he heard among the marching sound of men going forward to the dawn.

Back from Chile, Neruda joined forces with the liberation movement of the people and was elected by the tin miners to represent them in the national assembly. But this did not last too long. Soon the police were at him like a pack of mad dogs and he was forced to flee as he himself has written “through the tall night, through all our life”.

Having escaped from the hands of the butchers who ruled Chile at that time, Neruda went from country to country, attending conferences, reading his poems in the world, and inspiring men with hope and courage. Today, Neruda is back in Chile, or back at home once again doing his job, the job of a poet, which is to stand proudly on the side of truth and hope in a world full of ugliness and tumult and struggle.

Thunder is proud to print a poem by such a man and poet.

Thunder Editorial, 1955