It feels cruel that if you search for “The Heartbreak Kid” on Google, the Farrelly Brothers lethargic 2007 comedy comes up first, rather than the 1972 Elaine May film that it is (somewhat) based on. It’s a familiar bugbear. SEO trends tend to prioritise newer work. Further, May’s sophomore film – and arguably her best successful – has been increasingly hard to find. It was released on DVD in the nineties, but copies have been increasingly hard to come by since.

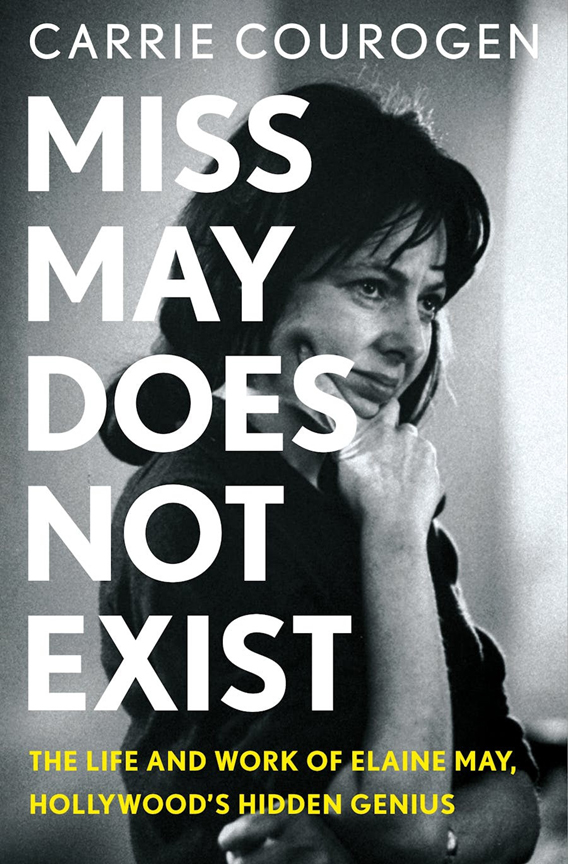

Metrograph, in New York, hosted a rare 35mm print of the film to celebrate the release of a new biography on May, Carrie Courogen’s “Miss May Does Not Exist”. More than 50 years after its release, the rhythms of this romantic comedy of errors are not the same as the sensibilities of contemporary romance, or comedy. Instead, the screening provided a welcome reminder of what sharp and excavating comedy can look like; of how laugh after laugh in an emphatic comedy could be punctuated with thoughtfulness as well as disarming depth; of how Elaine May’s skills as a filmmaker are worthy of the timely memorialisation of Courogen’s book; and of the essentiality of “The Heartbreak Kid” which, in its seductive slyness, is one of the hallmarks of 1970s comedy.

There are no heroes in “The Heartbreak Kid”, only people. Charles Grodin’s Lenny Cantrow is our not-quite-a-hero here. The opening sequence runs through a quick montage from date to flirtation to marriage as Lenny settles down with his very earnest wife Lila (May’s daughter, Jeannie Berlin).

They embark on their honeymoon less than ten minutes into the film, and the domestic bliss is very short-lived. Little by little we stay in Lenny’s perspective as he grows increasingly dismayed at the habits of his wife – her off-tone singing voice, her enthusiasm for her double-egg salad sandwich, her need for reassurance in bed. By the time their road-trip from New York ends at the hotel in Miami, and the appearance of the remote and glamorous college-student Kelly (Cybil Shepherd) the stage is set for Lenny to jettison one relationship in pursuit of another. That pursuit is complicated by Kelly’s domineering father (Eddie Albert) and from there the comedic complications only grow.

Even for film enthusiasts, much of May’s work is not as explicitly known as her male contemporaries. One of the thrills of Courogen’s book is the way it functions as both a biography of a great artist, and an essential book on filmmaking and the creative process. May’s four films get chapter focus, as do other creative events in her life. And the chapter on “The Heartbreak Kid”, just as the ones on her other films, emerge as vital cinematic knowledge for readers, even those who might be new to May. One compelling section of the chapter on the film talks of the dynamics of May’s working relationship with the screenwriter, playwright Neil Simon. One of the most prolific late-century American playwrights, Simon had so much cachet in Hollywood at the time that he was able to wield power more than most screenwriters – insisting that no line in the film could be changed without his approval. But comedy is more than words, and watching “The Heartbreak Kid” on a big screen in its 35mm glory.

There’s a lingering effect that’s central to the best of May’s work. Her early theatrical sketches with Mike Nichols, before they both achieved Hollywood fame, would draw great mileage from letting a punchline settle for a few seconds longer than you expect. It’s a quality that moves over into the comedic rhythms of her film work, too. As Lenny devises increasingly ridiculous lies to explain his absence to Lila, as he seeks out Kelly, May will refuse to leave a scene too fast. We stay in the absurdity and the discomfort.

Later on, when the film changes tracks and Lenny begins to woo Kelly’s father for her hand, the lingering moments become even more charged.

In some of the sharpest moments in “The Heartbreak Kid”, when Lenny’s unctuousness sits in sharp contrast to Albert’s circumspect father, a foolish statement lingers for a beat – emphasising the comedic absurdity but also the potential nuances for more. Courogen writes thoughtfully in her chapter on the film of the way May, “lingers in the silences, refusing to snap through lines at a rapid-fire setup/punchline pace. How she forces the audience to squirm, dealing in voyeuristic long take after long take, camera close, refusing to look away”. It’s a right, and sharp, assessment of the quality and one which reminds me most of what May, and other valuable American filmmakers who developed in the theatre, bring to cinema. The voyeuristic quality feels like a central quality of a filmmaker who knows the power of letting an audience espy the entirety of a set. Even as we focus on our primary fingers, the depth of the drama is found in letting us consider them in relation to the world around them.

A thing that struck about the lingering effect this time around is the vividness of the ensemble, many of them unnamed – or even silent characters. At the wedding that opens the film the camera lingers on faces, and bodies in the audience. In an increasingly absurd sequence where Lenny tries to extract himself from his wifely duties, Grodin runs through the halls of the hotel as the camera lingers on a couple observing him. The unnamed hotel guest even gets the punchline of the scene, one of the biggest laughs of the screening at Metrograph. In the climactic “bombshell” confession between husband and a wife, one particular female restaurant guest feels as meaningful as the couple themselves. A lesser, less adroit film might move from main characters to main characters but May’s explicit valuing of ensembles – of blocking in relation to minor characters – makes “The Heartbreak Kid” feel grounded in truth about human interactions, especially when its plot begins to escalate. The final sequence, a reception for another wedding, lands as effectively for that generous lingering on the minor characters emphasising the ambivalence of Lenny in that final shot.

Discomfort is the bedrock of some of the best works of comedy. There are many ways this faithless man and his capricious way could be played. The voyeuristic element the book speaks of in relation to May’s directorial vision is key to what makes “The Heartbreak Kid” so compelling half a century later. These are not great people, but they are also not inhuman. Even when they hurt each other. It would be hard to launch any kind of personality defence of Lenny, but May gives us the rope to hang him with. We sit in that discomfort and by its end, it’s her direction more than the script that challenges us to find something familiar and even strangely moving in him. Courogen’s account of the behind-the-scenes work May insisted on doing to ensure that discomfort was projected makes for one of the most enjoyable chapters in the novel. When she writes of May avoiding the broadness of Simon’s script in her direction, avoiding the instinct to go for “easy laughs without interrogation” it feels as emblematic of “The Heartbreak Kid” as it is about May’s entire career. Frame after frame, even when the laughter reaches a peak, May is always interrogating.

There are many laughs in “The Heartbreak Kid”, but very few of them come easy. And it’s that quality that makes them feel all the more worth it. Metrograph’s screening is a reminder of the charming rhythms of May’s work, and Courogen’s book is a welcome addition to the annals of works on valued filmmakers.

Now, if only someone can work on developing some reprints of “The Heartbreak Kid”…