By Nigel Westmaas

“Mi naw bow to Babylon!”..Mi neva bow to Babylon! Not even in de slave ship, mi jus keep quiet till when we reach land and whiteman pay money fi mi and tek mi fi cut cane up by some mountain, an before im coulda dream fuh beat mi mi gaan! Yes Maroon! Ariginal rebel! Spirit intact! Fram dat day to dis I & I live as a free man, and dats ’undreds a years, so mi nuh av no slave mentality, and mi nah bow to Babylon, white or black”

IZion, Rasta leader in Power Game (Percy Henzell)

Historical context and research challenges

Research on the Maroon resistance of the Americas, the Caribbean and Guyana is perhaps less extensive compared to the study of “formal” enslaved resistance, largely due to differences in historical documentation. While slavery and enslaved resistance was systematically recorded and documented through legal records, court trials of the enslaved, personal diaries, business ledgers, and government documents, Maroon communities often resided in hidden and remote areas, resulting in less comprehensive documentation and fewer primary sources for researchers. Thus academic and public historical narratives have traditionally concentrated on more dominant themes, such as the transatlantic slave trade, plantation economies, and “formal” abolitionist movements. Nonetheless, the legacy of the Maroons remains a subject of substantial academic and public interest and their history and influence can be explored through an interdisciplinary approach, combining history, anthropology, archaeology, and other fields, which can present challenges for researchers focused on traditional historical methods.

While both Maroon and enslaved resistance were pivotal in opposing slavery, they differed significantly in context, objectives, and outcomes. Maroon resistance was fundamentally about escaping subjugation to achieve freedom and self-governance. Conversely, plantation enslaved (as in testimony arising from the 1823 revolt) typically sought to improve living conditions or address specific abuses within the existing system of enslavement, when not in open resistance. This included overt acts of rebellion and sabotage as well as subtler forms of resistance like deliberate work slowdowns, feigning illness, and pilferage. Desertion from the plantation typically occurred in small numbers, a strategic choice that likely made escape more manageable and pursuit more difficult. The dense forests provided excellent cover, further complicating recovery efforts by the colonial authorities.

Such acts of resistance aimed at mitigating the harshness of their conditions, asserting dignity, and challenging the immediate injustices within the slavery framework.

Scholars such as James Rose, Alvin Thompson, Sylviane A Diouf, Richard Price, Kamau Brathwaite, Johnhennry Gonsalez, and more recently, David Alston, have significantly contributed to our understanding of Maroon activity and influence across the Americas, the Caribbean and Guyana. Maroon resistance, which aimed for freedom and self-governance, differed from that of the enslaved. The Maroons, also known by various names such as Palenques, Quilombos, Mocambos, “bush negroes”, Cumbes, Ladeiras, and Mambises, are groups that have played a pivotal role in the history of resistance against colonial slavery. The Maroon societies, composed of escaped slaves in the Americas, are also profound examples of cultural fusion, particularly between Amerindian and African traditions and various aspects of their rich cultural life in the “borderlands”, highlighting their culinary arts, music, military tactics, legal systems, medical practices, and manners. The fusion of these traditions is not merely a historical footnote; it is a vibrant testament to the enduring spirit and adaptability of the Maroon people.

Walter Rodney also commented on the issue of the runaways. He wrote, “the problems of runaways varied in acuteness depending mainly on environment. The forested area of Guyana offered conditions no less favourable to runaways than did Suriname and Brazil. In one period of Dutch ascendancy, intermingling between Amerindians and Africans produced the mixed ‘Boviander’ communities which were highly rebellious and constituted poles of attraction for runaways. …even the necessary activity of slaves ‘aback’ such as cutting palm trees for thatch, was considered dangerous since it facilitated escape.”

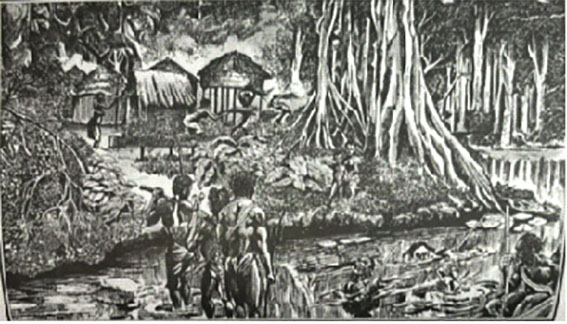

Maroon communities were a substantial economic and political threat to the colonial plantocracies. Maroons typically escaped to secure hideouts located in forested sections along coastlines, swamps, rivers, and creeks. They were adept at using the environment to their advantage, employing guerrilla tactics that were often compared with those used by notable resistance leaders in other regions, such as Zumbi in Brazil and Nanny and Cudjoe in Jamaica.

Their guerrilla warfare tactics were sometimes more debilitating to white power than open plantation rebellions, causing fear and contempt among planters. This contempt is evident in the dehumanising language used by the planters to describe the Maroons, with terms such as “beasts,” “snakes,” “gangrene,” “vermin,” “pernicious scum,” “chronic plague,” and “hydra.” The loss of slaves not only incurred direct costs but also put severe economic pressure on the plantation system and colonial governments. Laurens Storm vans Gravesande, a significant Dutch Governor during the time of Dutch colonisation of Guyana, frequently voiced his frustrations and concerns in his correspondence regarding the challenges posed by the Maroons.

European raids on Maroon camps often found them well-stocked with essential staples such as rice, yams, and cassava. Maroons cultivated a variety of crops including plantains, sugar cane, peas, peppers, tanje (tannia), tobacco, calabash, wingrain (warigula), basil, Indian corn, pumpkins, limes, and okras. This agricultural base was supplemented by fishing and hunting, supporting a robust and self-sufficient economy. For example, in 1810, a militia captain in Demerara, Edmonstone, cited a Maroon community in the Abary-Mahaicony area that had 14 houses surrounded by rice fields, which he estimated could feed 700 men for a year, in addition to providing ground provisions and tobacco.

Music within Maroon communities was predominantly influenced by African traditions. The rhythms, instruments, and melodies carried over from African ancestors have been preserved and adapted.

The Maroons likewise developed a structured system to handle disputes, reflecting a sophisticated understanding of governance. When a person raised a complaint, it was brought before a council at a predetermined time and place. Here, each party presented its case, and a resolution was typically reached during the session, demonstrating a democratic and efficient legal process within these communities.

Maroon societies maintained high standards of conduct and had their unique medical, legal, and cultural practices. In medical practices, Maroons considered themselves unparalleled herbalists, utilising a vast array of native herbs—an amalgamation of African herbal knowledge and Amerindian plant usage. Remedies ranged from cold treatments involving ingredients like cow tongue and rat-ears to the use of nutmeg paste for serious wounds, indicating a deep empirical knowledge of natural medicine.

The Guyana Maroons in particular

The population of Maroons in British Guiana was difficult to assess, with figures ranging from as few as 2,000 to as many as 12,000. Marronage saw a notable increase after the 1763 rebellion. In 1744 according to Thompson, there were approximately 300 Maroons in northwest Essequibo, sited in large encampments. The prevalence of marronage seemed to increase following the 1763 Berbice rebellion, indicating a growing resistance movement. By the 1790s, it was estimated that there were about eight Maroon communities in Demerara alone. The 1795 Demerara revolt was a significant event that strained military and financial resources considerably.

Earlier, in 1744, around 300 Maroons were reported to be living in large encampments in northwest Essequibo. By 1767-68, a small group of about 50 had moved from Berbice to Essequibo-Demerara, demonstrating the fluid and dynamic nature of Maroon settlements. In 1773, the activities of the Maroon communities led the colonial government in Suriname to declare financial bankruptcy.

The scale of marronage activity in Guyana never reached the levels observed in Suriname, such as those of the Saramaka or Djuka Maroons. Suriname’s Maroons, for instance, were significant enough to negotiate peace treaties (as in the case of Jamaica with the English) with the Dutch in the mid-18th century, although these treaties were followed by renewed conflicts. Yet, while rarely acknowledged, Guyana maroon communities were known for their highly developed, independent societies and their harassment of the “formal” colonial plantation slave society.

David Alston, an independent Scottish scholar, has produced updated research on Guiana Maroons and concluded that Guiana Maroon activity, or what he calls “borderland marronage,” did not die off in the 1790s but continued all the way up until the formal abolition of slavery in 1834. He substantiated his claim that the Guyana Maroons “were a significant and enduring presence” by asserting that from “the last decade of the eighteenth century until emancipation in 1834, Maroon communities were larger, more resilient, and more enduring than has been recognized.” In support of this contention, he identified the activity of the Guyana Maroons in conjunction with enslaved resistance in 1795, 1810, 1814, 1823, and all the way to 1834.

Significantly, Alston showed how the huge Demerara revolt of 1823 held some important and unexplored relationships with the Maroons in existence at the time of the coast revolt. He asserted that both the Demerara revolt leaders, father and son Gladstone and Quamina, “were said to have referred to Maroons being willing to join the insurgents, with reports, attributed to Jack Gladstone, of a ‘thousand Bush negroes’ who might come from Wakenaam island in the mouth of the Essequibo river.”

Alston described one European expedition in 1818 comprising militia and Amerindians that attacked Maroons in the area of New Beehive and Greenfield on the East Coast Demerara and captured one leader named Frank. According to Alston, “Captain Frank, ‘dressed in all the paraphernalia of obeism(sic)’ was hanged at New Beehive” and his body “was decapitated and his head was placed on a pole,” an act that was typical of plantation repression by Europeans throughout the Americas and Caribbean.

The Maroons in Guyana, much like their counterparts in places like Suriname and Haiti, represented complex socio-political entities that navigated between resistance and negotiation with colonial powers.

This “negotiation” and political contracts with colonial powers from “borderland” to plantation complex also involved counter revolutionary action by the maroons on enslaved Africans on the plantation and this extended to “catching runaways for slaveholders.”

Historical accounts, such as those by James Rose (who has published more directly on the 1795 Maroon revolt) and others, draw regional comparisons and delve into the interactions — conflicts and alliances — between Maroon communities and Amerindian groups, as well as enslaved plantation populations. Maroons, in essence, embraced a unique conception of freedom. This conception was both compromising and uncompromising in relation to political spaces, organisation, government, and fierce preservation of independence.

Economically, the impact of marronage was profound. Every escaped slave represented not just a loss of labour but also a direct financial cost. Maroon assaults intensified the economic pressure on the plantation system and colonial governments.

The strain was not only economic but also military. The 1795 Demerara revolt, for example, exerted tremendous pressure on the colonial forces, costing them heavily both in terms of military expenditure and human resources. James Rose recounts how Maroon community expeditions at the time, “numbering in excess of a hundred” attacked plantations at Canal Number One and Windsor Forest. The Maroon leader, Amsterdam, deemed “the supreme leader and military commander” of the Maroons of 1795, was eventually captured and subjected to extreme torture before his execution. Yet, according to Dutch accounts, Amsterdam withstood all the torture and “regarded the bye-standers with all the complacency of heroic fortitude, and exhibiting the most unyielding courage…” could not “extort from him a single groan; or a syllable that could in any way impeach his friends.”

In summary, the Maroons of the Guianas represented a significant resistance movement that continuously challenged the colonial and plantation systems through both passive resistance and active conflict. Their persistent defiance not only disrupted the oppressive structures but also inspired other forms of resistance among enslaved populations. As evidenced by the enslaved uprising in Berbice in 1763, which sent shockwaves in the Guiana colonies and the region long before the Haitian revolution of 1791-1804, the Maroons exemplified the spirit of rebellion and the relentless pursuit of freedom. As IZion aptly stated, they were the “ariginal” rebels, embodying the indomitable will to resist and survive against all odds.