By Nigel Westmaas

The issue of poor preservation of Guyana’s archives, as highlighted by Walter Rodney, is not a recent concern. As far back as 1936, the superintendent of the British Guiana archives raised alarms about the “indiscriminate and ruthless destruction of important historical records.” Historically, many vital Guyanese records were stored in the dome of the Public Buildings, leaving them vulnerable to threats such as water damage, dampness, mould, neglect, and insects, including destructive wood ants.

When Hugh “Tommy” Payne joined the National Archives in 1965 and later became the official archivist in 1970, he noted the low regard in which the Archives Department was held at the state level. Payne ultimately resigned in 1988, frustrated by the lack of conservation efforts and the inadequate funding for preserving archival documents.

In the 1970s, Joel Benjamin wrote a discerning article, “Archival Resources for the Study of Guyanese History,” which assessed both the range and the condition of the country’s archives and the national response to their preservation. His was among many voices, before and after independence, that highlighted the state and importance of Guyana’s archives as crucial sources of national memory.

The role(s) of archives

Archives serve as the principal repositories of historical documents, artefacts, and records, playing a critical role in understanding a nation’s history and identity. They shape national narratives by selecting what is preserved and how it is presented to the public. This curation reinforces a sense of unity and distinctiveness, which is vital for political nationalism.

Political leaders often utilise historical narratives from archives to legitimise current political agendas. By highlighting specific historical events or figures that resonate with nationalist ideologies, they can bolster their legitimacy and garner public support. But this selective use of history may lead to a skewed or biased interpretation of the past. For instance, commemorations of significant historical anniversaries rely on records and artefacts preserved in archives. However, the choices used in these commemorations can often be politically motivated, transient, and superficial.

In educational settings, the materials from archives influence how history is taught. The portrayal of historical events shapes young minds, potentially fostering a nationalist outlook by influencing their views on national identity and loyalty.

Internationally, archives can affect a country’s image and influence its diplomatic relations. For example, historical disputes over territories, war crimes, or colonial legacies—often grounded in archival documents—can affect nationalist policies and international diplomacy. The defence strategy against Venezuela (including taking the country to the World Court), for example, presumably relies on archival documentation and research and primary and secondary sources. .

Furthermore, archives and historical collections are vital for fostering national cohesion and a non-partisan appreciation of achievements. The term ‘archive’ traditionally refers to a collection of documents and newspapers maintained in controlled environments within designated buildings by library systems, ministries, or state functionaries. However, it also encompasses informal sources like personal collections, sound recordings, old political flyers, films, photographs, the British Guiana matchbox, unfinished class notes, Amerindian rock paintings, and overlooked works of Guyanese artists, musicians, scientists, and writers, including mundane letters. These items, though perhaps underappreciated initially, can gain significant historical importance and contribute to the nation’s collective memory. National or localised archives often provide dedicated spaces for researchers, scholars, and the public to access and study these materials, including reading rooms and computer stations for accessing digital archives.

Efforts to engage with the public and other institutions, including schools, universities, and other archives, are important. Collaborations can help expand the reach and resources of an archive.

Memory, records and archives serve as a foundational element in the construction of national identity. In Guyana, collective memory encapsulates a blend of indigenous traditions, the legacies of European colonisation, African enslavement, Indian indentureship and the historical subjugation of Amerindians. These memories, transmitted across generations through oral histories, music, and cultural practices, form a unique historical identity that is distinctly Guyanese.

Memory, records and archives serve as a foundational element in the construction of national identity. In Guyana, collective memory encapsulates a blend of indigenous traditions, the legacies of European colonisation, African enslavement, Indian indentureship and the historical subjugation of Amerindians. These memories, transmitted across generations through oral histories, music, and cultural practices, form a unique historical identity that is distinctly Guyanese.

What about popular history?

Memory is inherently selective and subjective. In Guyana, the prominence of certain narratives often eclipses others, particularly those of marginalised communities. This selective memory can result in a skewed perception of history that does not accurately reflect the diverse experiences of all Guyanese people. For example, narratives around Guyana’s political history are often constrained by an overwhelming, mind numbing focus on the two main political parties. But what about the lesser-known political entities like the Guiana United Muslim Party (GUMP) of the early 1960s, the British Guiana Labour Party (founded in 1946), the Brotherhood Movement of British Guiana (1928), the Guiana African Association (1842), and so many others?

The popularisation of Guyanese history faces significant challenges. Media representation plays a crucial role here. There is a pressing need for media outlets to feature historical content that is informative and appealing to a broader audience. To address these challenges, several strategies could be employed. Educational reforms are essential; the school curriculum can be revised to include detailed studies of Guyanese history from a variety of perspectives. This would help cultivate a more well-rounded understanding of the nation’s past among young people.

However, there is an apparent disdain for historical material from some typified by the cynical remark, ‘We have economic challenges, and all you can talk about is archives? How that gon feed me?’

Despite these understandable challenges confronting the preservation and popularisation of history, institutions such as the Frank Narain Parliamentary Library, the National Library, the Caribbean Research Library at the University of Guyana, the Walter Rodney National Archives, and the Cheddi Jagan Research Institute continue to play a vital role in preserving the national memory. Additionally, there are smaller rural collections that contribute significantly, including the “little museum” in Meten-Meer-Zorg, run by a local collector of Guyanese historical items and in existence in the early 2000s, and the most recent iteration of dedicated holders of collections, the Buxton/Friendship Museum, Archives & Culture Centre, established in 2018.

Other more literary fragments of national recall supported by a vast, mostly forgotten series of journals and magazines once graced the shelves and people’s homes in colonial and independent Guyana. From the New World journal, Kyk-Over-Al, Chronicle Christmas Annual, all through to the current Emancipation magazine – the country has an unrecorded and very deep base of thinking and writing from which to draw. Other collections can be found in various volumes and institutions that warrants attention and resolve to go look – the Hansard record of parliamentary proceedings, Timehri journals, paintings of the National Collection at Castellani house are among other storehouses of things Guyanese. The staff at the Caribbean Research Library at the University of Guyana, much like those at the Walter Rodney Archives, continue to do a remarkable job in collecting, storing, protecting, and making available key documents on Guyanese history.

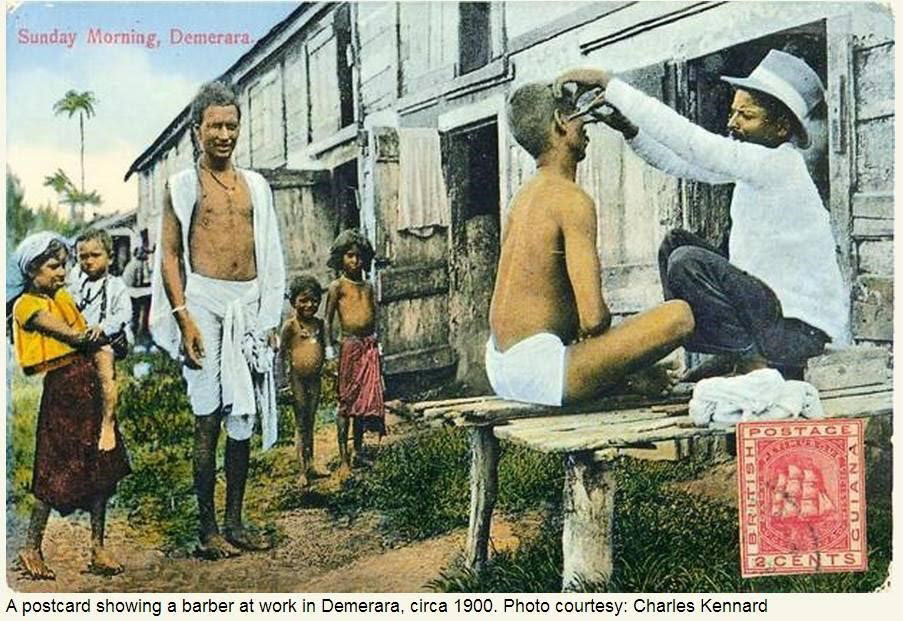

Additionally, there are missed opportunities in recognising national memory through collecting memorabilia or interviewing individuals who recall past events. This oversight extends to various groups including dock workers, artists, politicians, and educators, whose contributions are often unrecognised amid the hustle of daily life. If national consciousness is ongoing then the simple things we throw away, then and now, from an old matchbox, an aged letter, or old postcard are extremely valuable as symbols for a national memory archive.

As early as 2008, an editorial in the Stabroek News raised concerns about the improper storage of historical radio recordings, as highlighted by Denis Chabrol and Gordon Burnett. These journalists pointed out, out of concern, that valuable reel-to-reel tapes and records were stored inadequately, illustrating a broader issue of neglect in preserving tangible historical materials.

There are so many fronts in the assembly of the national memory, from recall via oral history to an old political pamphlet from the 1950s should be valuable for national memory. A curiosity check of the old main newspapers of the past would witness a consistent trend of regular letter writers and pugnacious and informative columnists and elaborate court reporting that even eclipses modern court reporting for accuracy and detail.

The sources or ‘outposts’ of this national memory, in whatever form, can be found in many places, including the archives of the many inveterate collectors in Guyana and abroad. I am sure veteran archivists and collectors would love a peer at the personal collections of some senior Guyanese citizens.

Perhaps a nonpartisan commitment to “national memory and bibliography” ought to be established. This group or institution can be made responsible for seeking, borrowing, copying and making available the oral testimonies, private archives of citizens, and valuable records into the nonpartisan memory reservoir.

In this computer age of flash drives, old letters in the drawer, rare photographs uncovered, should perhaps be assembled and copied with compensation and permission of owners into central rural and urban locations, for the benefit of all Guyanese. One possibility might be a “national collection day” or sharing of memorabilia. Augmented by scanners and the facility of even the new iPhone, can add substantially, along with oral history, to the country’s records.

Earlier this year, a budget allocation of $2.7 billion was announced for the “revitalisation of the nation’s cultural landscape,” including the establishment of a new art gallery and museum. It is not immediately clear whether this means that the existing museums, art galleries, and their accompanying buildings will be expanded or if entirely new structures are planned. Whatever the plan, it must reflect a shift towards a non-partisan, open project that involves broad consultation.

The struggle to popularise Guyanese history is fraught with challenges not last of all a national inertia with things historical, yet it remains a crucial endeavour for fostering a well-informed and cohesive national identity. Central to this mission is the effective use of memory and archives. By investing in these resources, Guyana can preserve its rich past and ensure it is celebrated and understood by future generations. This effort is essential for enriching the country’s historical consciousness and for contributing to a more nuanced and inclusive global historical narrative.

In order to achieve this, Guyana must implement strategic educational and cultural initiatives that engage its citizens, especially the youth, in the study and appreciation of their national history. Educational curriculums need to be enriched with comprehensive local history and cultural programs celebrating the diverse heritage of the nation through festivals, exhibitions, and public lectures. Additionally, the enhancement of digital archives and accessibility to historical resources will enable a wider and more inclusive participation in the nation’s historical discourse.

Few have established the link between the possibility of the archive and national cohesion more clearly than George Lamming, the Caribbean literary icon. One of his key insights underscore the crucial role of interdisciplinary collaboration in realising a comprehensive national historical narrative:

“…this is my suggestion, where the concept of archive and epistemology come together; it is possible, the political leader could arrive at such a vision if he enjoyed a certain measure of collaborative support from other modes of thought and perception; from the historian, the poet, the student of philosophy, and the social scientist, the economist, the theatre director who recreates the cultural history of the nation. It is the collective dialogue between these different categories of sensibility which ultimately gives voice to a commanding vision of a new society.”

Embracing Lamming’s perspective, it becomes evident that building a robust historical consciousness requires a multidisciplinary approach. By fostering a dialogue that includes historians, artists, economists, and scientists, Guyana can forge a historical narrative that is not only rich and inclusive but also instrumental in shaping a visionary and cohesive national identity.

While oil may not spoil, a nation’s memory and its preservation can be severely damaged by an indifference to issues beyond the relentless pursuit of oil revenues, especially when those revenues are spent on matters seemingly unrelated to the development of the human spirit.