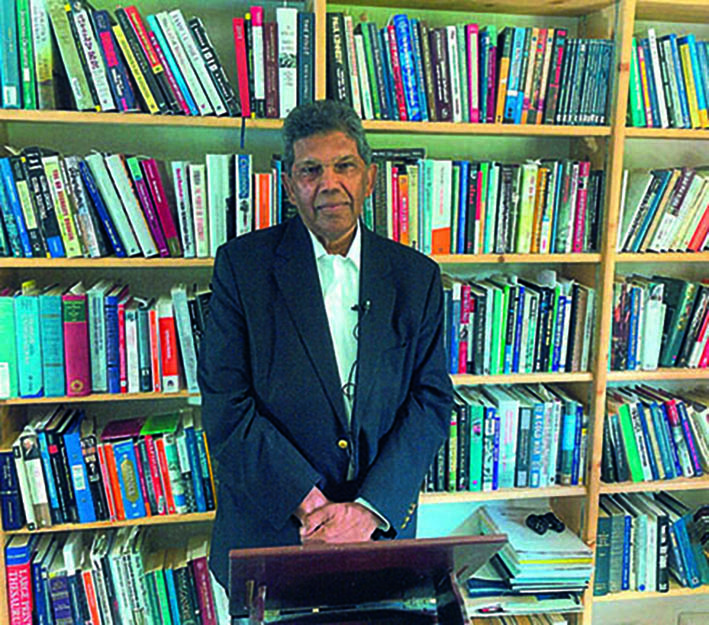

By Dr Bertrand Ramcharan

Seventh Chancellor of the University of Guyana

Sometime Fellow of Harvard University and Fellow of the LSE

In an eye-opening and much acclaimed new book, Autocracy Inc., celebrated journalist and author Anne Applebaum writes: “There is no liberal world order anymore, and the aspiration to create one no longer seems real. But there are liberal societies, open and free countries that offer a better chance for people to live useful lives than closed dictatorships do. They are hardly perfect. Those that exist have deep flaws, profound divisions, and terrible historical scars. But that’s all the more reason to defend and protect them.”

In contrast to such liberal societies, she writes, “the strongmen who lead Russia, China, Iran, North Korea, Vene-zuela, Nicaragua, Angola, Myanmar, Cuba, Syria, Zimbabwe, Mali, Belarus, Sudan, Azerbaijan, and perhaps three dozen others, share a determination to deprive their citizens of any real influence or public voice, to push back against all forms of transparency or accountability, and to repress anyone, at home and abroad, who challenges them. They also share a brutally pragmatic approach to wealth”.

Their bonds with one another, and with their friends in the democratic world, she continues, are cemented not through ideals but through deals – deals designed to take the edge off sanctions, to exchange surveillance technology, and to help one another get rich.

The details in this book are staggering of the efforts within this group of countries to overturn the principles and rules of the United Nations Charter, to move away from notions of constitutional governance, the rule of law, the concept of shared human dignity, and universal values of human rights. We will leave it to the reader to read these details to herself or himself. Applebaum summarises the global predicament thus: A world in which autocracies work together to stay in power, work together to promote their system, and work together to damage democracy is not some distant dystopia. That world is the one we are living in right now.

The situation prevailing in Venezuela is one that Guyanese would do well to take note of. Applebaum writes about the “Maduro model” of governance: Autocrats who adopt it are “willing to see their country enter the category of failed states”, accepting economic collapse, endemic violence, mass poverty and international isolation if that’s what it takes to stay in power. And Maduro receives unstinting support from his friends in Autocracy Inc. Applebaum writes: “Iran, plus Russia, China, and Turkey have kept the profoundly unpopular Venezuelan regime afloat and even allowed it to support autocrats elsewhere.” The Venezuelans, for their part, might have helped launder money for Hezbollah…and are believed to have provided passports for Hezbollah and Iranian officials as well.

Why mention Maduro’s Venezuela here? Because, in the context of the on-going electoral imbroglio, with the Presidents of Brazil and the USA calling for new elections in Venezuela, it should come as no surprise to anyone if the “Maduro model” were to resort to active aggression against Guyana’s Essequibo – with support from Autocracy Inc.

Returning to the question posed in the title of this essay: “Whither Guyana: Autocracy or Democracy?”, some historical context is necessary, and we will present this factually and clinically: Prior to attaining its independence, Guyana was a violent theatre of the Cold War. Dr Cheddi Jagan was branded a communist and he and the PPP were shunted from power. Forbes Burnham, then wearing the cloak of a democrat, took Guyana into independence and proceeded to do the following things: rig elections blatantly and massively; replace the Independence Constitution through a fraudulent referendum; declare the PNC a Marxist Leninist party – the ‘vanguard party’; place the party above the Government; and exercise dictatorial powers as an all-powerful Executive President. These are all established historical facts.

Burnham’s successor, Desmond Hoyte also rigged elections but then, under international pressure following the end of the Cold War in 1989, accepted free and fair elections in 1992. Between 1992 and 2020 there have been various shades of instability around each election held. There has been one distinguishing feature of this instability: the PNC has not been willing to accept the result of most of these elections, with resultant disorder and violence. It did come to power fairly with a slender majority in 2015 but the evidence is overwhelming that it illegally sought to remain in power even though it had lost the elections in 2020.

As elections approach in 2025, leading PNCR advocates – and others of goodwill – are calling for a changed system of governance and for inclusive governance, or for power-sharing. Those now in government have, so far, side-stepped such calls and, although a Parliamentary commission has been established to look at constitutional changes, it remains to be seen whether any such change will come about in the year or so before elections are due. As far as is known, the commission has been largely inactive since its establishment.

It is in this context that the question arises for reflection as to Guyana’s future path from the perspectives of autocracy or democracy. Two historical facts stand out: first, the PNCR has a record of subverting elections; and, second, the PPP has a record of autocratic tendencies.

How so? In 2009, Applebaum writes, Uganda passed a law giving a government board the power to regulate and even dissolve domestic civic organizations. An Ethiopian version of the same law gave a similar board the right to abolish organizations if they are deemed “prejudicial to public peace, welfare, or good order in Ethiopia”, language sufficiently vague to allow the abolition of almost any organization. Cambodia passed a law banning any organizations whose activities “jeopardize peace, stability, and public order or harm the national security, national unity, culture and traditions of Cambodian society,” which pretty much covers any activity the government wants to ban.

In January 2024, Venezuela’s National Assembly took up a new law that would allow the government to dissolve NGOs and impose heavy fines on their members for breaking any of a long list of arbitrary requirements. Cuba, which, according to Applebaum, has not registered any independent organizations since 1985, has recently arrested hundreds of people who participated in informal groups too.

In Guyana, we have recently seen official inquisitions into the tax status of NGOs, calls for new laws to ‘regulate’ NGOs, and public campaigns of vilification against particular NGOs and their leaders. There are shades of autocracy here, without a doubt. And Guyana has also seen ‘highest level’ admonitions of judges carrying out their duties in good faith.

There are also other shades of autocracy: Parliamentary scrutiny of governmental activity is minimal, if existent. Governmental consultation with the opposition is hardly existent. Oil money has made the Government lush with funds for information campaigns. And an Oracle in the ruling party pronounces on all matters, big and small. The spirit of governance smells of autocracy.

Guyana’s historical record is thus a blemished one when it comes to assessing it from the perspectives of autocracy and democracy: one party has subverted elections, while the other party practices “All is mine.”

One must, however, distinguish between parties and people. There can be no doubt that the Guyanese people, across the board, are a freedom-loving people, in favour of democracy, the rule of law, and respect for fundamental human rights. This is a part of their DNA. Guyana and Guyanese share this with their Caribbean sisters and brothers, and with their sisters and brothers in North and South America.

In the coming global struggle then, between Autocracy Inc. and Democracy Inc., Guyana belongs squarely within the sphere of Democracy Inc. It would help us to navigate our way inside Democracy Inc. if we could negotiate a new system of governance that would give every Guyanese a sense of belonging, or ownership, of their system of Governance.

So far, no leader of any of the political parties has been able to rise to this challenge of leading us to a system of governance in which every Guyanese would feel that she or he has a stake. And none of the leading parties has thus far risen to this challenge.

Until Guyana succeeds in devising a trusted system of governance, it will remain precariously poised between democracy and autocracy, with vibes of autocracy manifesting themselves in the governance of the country.

And the Oracle, whatever it says, will remain an irrelevance in the judgment of history.