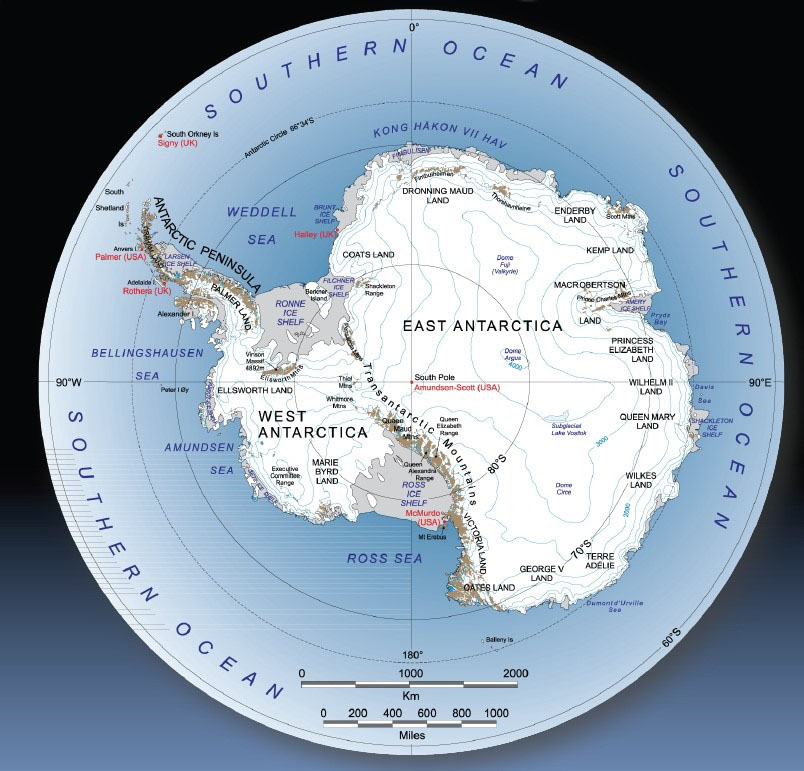

PUCON, Chile, (Reuters) – Nearly 1,500 academics, researchers and scientists specializing in Antarctica gathered in southern Chile for the 11th Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research conference this week to share the most cutting-edge research from the vast white continent.

Nearly every aspect of science, from geology to biology and glaciology to arts, was covered but a major undercurrent ran through the conference. Antarctica is changing, faster than expected.

Extreme weather events in the ice-covered continent were no longer hypothetical presentations, but first-hand accounts from researchers about heavy rainfall, intense heat waves and sudden Foehn (strong dry winds) events at research stations that led to mass melting, giant glacier break-offs and dangerous weather conditions with global implications.

With detailed weather station and satellite data dating back only about 40 years, scientists wondered whether these events meant Antarctica had reached a tipping point, or a point of accelerated and irreversible sea ice loss from the West Antarctic ice sheet.

“There’s uncertainty about whether the current observations indicate a temporary dip or a downward plunge (of sea ice),” said Liz Keller, a paleoclimate specialist from the Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand that led a session about predicting and detecting tipping points in Antarctica.

NASA estimates show the Antarctic ice sheet has enough ice to raise the global mean sea level by up to 58 meters. Studies have shown that about a third of the world’s population lives below 100 vertical meters of sea level.

While it’s tough to determine whether we’ve hit a “point of no return,” Keller says that it’s clear the rate of change is unprecedented.

“You might see the same rise in CO2 over thousands of years, and now it’s happened in 100 years,” Keller said.

Mike Weber, a paleooceanographer from Germany’s University of Bonn, who specializes in Antarctic ice sheet stability, says sediment records dating back 21,000 years show similar periods of accelerated ice melt.

The ice sheet has experienced similar accelerated ice mass loss at least eight times, Weber said, with acceleration beginning over a few decades that kick off a phase of ice loss that can last centuries, leading to dramatically higher sea levels around the world.

Weber says ice loss has picked up over the last decade, and the question is whether it’s already kicked off a centuries-long phase or not.

“Maybe we’re entering such a phase right now,” Weber said. “If we are, at least for now, there will be no stopping it.”

While some say the climate changes are already locked in, scientists agreed that the worst case scenarios can still be avoided by dramatically reducing fossil fuel emissions.

Weber says the earth’s crust rebounds in response to retreating glaciers and their diminishing weight could balance out sea level rise, and new research published weeks ago shows that a balance is still possible if the rate of change is slow enough.

“If we keep emissions low, we can stop this eventually,” said Weber. “If we keep them high, we have a runaway situation and we cannot do anything.”

Mathieu Casado, a paleoclimate and polar meteorologist at France’s Climate and Environment Sciences Laboratory, specializes in studying water isotopes to reconstruct historical temperatures.

Casado said data from dozens of ice cores collected throughout the ice sheet has allowed him to reconstruct temperature patterns in Antarctica dating back 800,000 years.

Casado’s research showed that the current temperature rise in the last fifty years was clearly outside natural variability, highlighting the role of industry in producing carbon emissions that drive climate change.

He added that the last time the Earth was this warm was 125,000 years ago and sea levels were 6 to 9 meters higher “with quite a bit of contribution for West Antarctica.”

Temperature and carbon dioxide were historically at equilibrium and balanced each other out, Casado said, but we currently have much higher levels of CO2 and are far from equilibrium.

Casado and other scientists noted the speed and quantity at which carbon is being pumped into the atmosphere is unprecedented.

Gino Casassa, a glaciologist and head of Chilean Antarctic Institute, said that current estimates show sea levels rising by 4 meters by 2100 and more if emissions continue to grow.

“What happens in Antarctica doesn’t stay in Antarctica,” said Casassa, adding that global atmospheric, ocean and weather patterns are linked to the continent.

“Antarctica isn’t just an ice refrigerator isolated from the rest of the planet that has no impact.”