(BBC) Contemporary paintings celebrate the brave women who fought fiercely alongside the men in the Haitian revolution of the 18th Century. How did they contribute, and why have their stories been buried for so long?

On the night of 23 August 1791 in Cap-Français, on the north coast of Saint Domingue (present-day Haiti), fires raged on the plantations. The enslaved set fire to the buildings and fields, and killed their masters. It was the start of the Haitian Revolution, the only known uprising of enslaved people in history that led to the founding of a state that was free from slavery.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic in France, news was fast spreading about the uprisings. The wealthy ruling elite and those with a monopoly in the transatlantic slave trade were growing anxious. They began to realise that their days of subjugating the enslaved population for profit were coming to an end. The coordinated attacks was the beginning of an armed resistance that sprung up across the country in the following years.

The enslaved rebellions ultimately led to the previously unthinkable; the dismantling of the colonial system and the declaration of Haiti’s independence in 1804. It was “the first successful large-scale revolt by enslaved people in history”, and the country became the first free black republic in the world, and the first independent Caribbean state.

History mostly remembers the exploits of male freedom fighters of the Haitian Revolution. Figures such as its leader, General Toussaint Louverture; Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who became the first ruler of an independent Haiti; Dutty Boukman who was leader of the Maroons and a vodou priest, or houngan; the first and only King of Haiti Henri Christophe, and others. Their stories have been chronicled and commemorated through time.

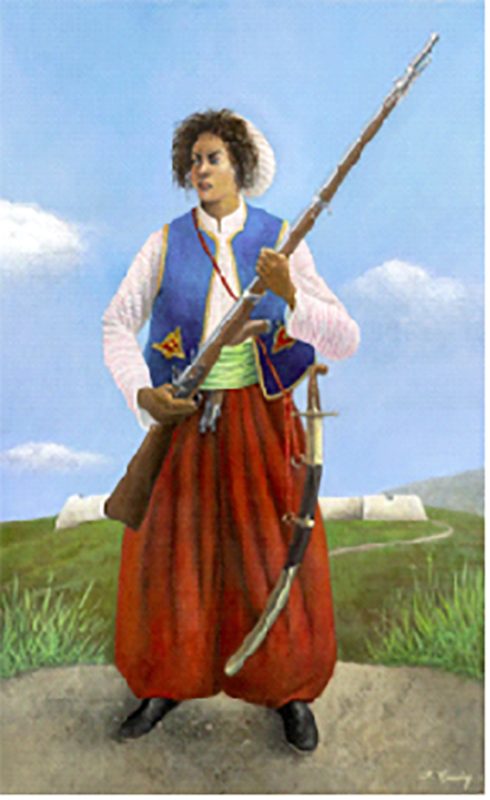

Marie Jeanne Lamartiniére, portrayed by artist Francois Cauvin, wore male uniform and fought alongside men in the revolution (Credit: Courtesy of the artist, Francois Cauvin)

Marie Jeanne Lamartiniére, portrayed by artist Francois Cauvin, wore male uniform and fought alongside men in the revolution (Credit: Courtesy of the artist, Francois Cauvin)

Yet there were also women who had key roles in the fight for Haiti’s independence. Much of their history is unknown in the mainstream, or underrepresented and overlooked due to the lack of documentation and records of their activities. However the stories we do know of women including Sanité Bélair, Cécile Fatiman, Marie-Jeanne Lamartiniére, Catherine Flon, Suzanne Simone Baptiste Louverture and more, detail their determination, bravery and dedication to the cause against all odds.

There’s also a lack of visual evidence of these women. However, contemporary artists Richard Barbot and François Cauvin – both Haitian – have reimagined them, providing faces to the names. Cauvin’s painting of Lamartiniére will be part of The Fitzwilliam Museum exhibition Resistance, Revolution and Reform: Cambridge and the Caribbean in the Age of Abolition in 2025.

Dr Crystal Nicole Eddins, associate professor of sociology at the University of Pittsburgh and author of Rituals, Runaways, and the Haitian Revolution: Collective Action in the African Diaspora, tells the BBC that women employed various tactics of resistance, from overt action, to working quietly behind the scenes. Some, including Bélair and Lamartiniére, were fighting on the frontlines. “We know that women were taking up arms alongside men. Women from African societies held a wide range of social roles, some of which were militaristic, in addition to the fact that women were also labouring on plantations, doing the same work as men. So it follows that they were fighting the same fight.”

There were healers and nurses like Catherine Flon – who is mostly known for being a seamstress, and is said to have sewn the newly independent Haiti’s first flag – as well as educators, spies and saboteurs who used guerilla tactics to sabotage resources, including water supplies, of their enemies. Eddins explains that women also contributed to more gendered roles such as growing and providing food for the rebel armies and their communities.

Sanité Bélair, depicted by Haitian artist Richard Barbot, was a revolutionary who led the charge at Saint-Domingue (Credit: Courtesy of the artist, Richard Barbot)

Sanité Bélair, depicted by Haitian artist Richard Barbot, was a revolutionary who led the charge at Saint-Domingue (Credit: Courtesy of the artist, Richard Barbot)

Sanité Bélair was a Haitian revolutionary leader who served in Toussaint Louverture’s army. She rose through the ranks, first as a sergeant then a lieutenant, leading the charge in the Saint-Domingue expedition. Alongside her husband Charles Bélair, another lieutenant in the army, they were eventually captured and executed on orders from Napoleon. Bélair’s legacy is commemorated with her portrait on the Haitian 10 gourdes banknote, created in 2004 as part of a series celebrating the 200th anniversary of Haiti’s independence.

Less well known were the vodou priestesses (mambos) and spiritually powerful women like Cécile Fatiman, who provided “protection spells” to the rebels, and refused to give up information about their location. They also used their traditional knowledge of herbal medicine to poison slave owners.

Born to an enslaved African woman and a Corsican prince, Fatiman was a prominent mambo and revolutionary who is also said to have created networks of communication transporting information across the plantations. She lived to a remarkable 112 years old.

Marie-Jeanne Lamartiniére was a Haitian soldier and nurse who is celebrated not only for her courage but also for her knowledge and strategy on the battlefield. Wearing male uniform and fighting alongside the men, she was highly respected. Lamartiniére was a key figure in the major Battle of Crête-á-Pierrot in 1802 against French forces.

Women were not exempt from the punishments meted out for participating in the revolution, and they suffered the same brutal fates as men. Bélair was famously known to have refused the blindfold before being executed alongside her husband by the French. “She’s described by earlier historians’ accounts and in CLR James’s book The Black Jacobins, as having been a really brave woman who promoted the fight for independence,” says Eddins.

With the few details we know of Bélair and other women, chroniclers have written about their bravery and determination for the liberation cause. “In some cases, historians have said that it was the women who were the most fierce in their fight.” They subverted colonial oppressions, and, in the face of adversity, fought for agency within their communities and society at large.

Resisting slavery

The colonists created divisions between the enslaved – sowing discord with invented hierarchical systems involving religion and skin tone. By using the divide-and-conquer tactic, colonists hoped that they would be too busy fighting among themselves to break the chains of slavery. In addition, they threatened extreme violence as punishment for insurrection. However, it did not deter the enslaved people’s desire for liberation. They organised revolts without the knowledge of their masters, who were oblivious due to their perceived sense of safety, and their mistaken belief that black people were inferior and incapable of fighting for themselves.

During the period of slavery, vodou created the environment for people to meet, and share cultural ideals and political alliances.

This belief especially persisted in the way black women were viewed. Many took leadership positions in the organised rebellions, though we don’t know much about their stories. Eddins says that newer literature is investigating why these women were silenced in records. Their enslaved status is part of it, according to Eddins, and also according to NYU professor of history Jennifer L Morgan who has also researched this. Eddins says: “[Professor Morgan] talks about how slave status was conferred through the womb of African women, that enslavers didn’t want to see them as human, because if they saw a pregnant woman, that would remind them that African people had kin and had family.” Also, enslavers were unlikely to view black women as being revolutionary or having rebellious inclinations.

Another reason for their lack of visibility in the history books is the fact that there aren’t enough first-person narratives of these women. Eddins says: “We have letters from Toussaint Louverture. We have writings by Jean-Jacques Dessalines, but we don’t have, at least to my knowledge, any known writings from a woman revolutionary. So in the absence of that, it takes creativity to try to figure out how to find these women, and make sense of their stories.” With her next project, Eddins hopes to find other women like Fatiman and Bélair, and make Haitian revolutionary women’s stories more visible.

Dessalines Ripping the White from the Flag by Madsen Mompremier (Credit: Courtesy of the artist/ Fowler Museum at UCLA)

A vodou ceremony known as the Bois Caiman is said to have sparked the Haitian Revolution. Originally, this indigenous African diasporic religion – later developed in Haiti as a response to slavery – was a worship of the elements: earth, sun, water and air. Vodun worshipers believed that there is a connection between the land of the living and the spirit realm. Death is seen as a transition to the invisible world where their ancestors guide and watch over them on Earth. Over the years, due to misconceptions and characterisations by the West, it has become a stigmatised spiritual practice. During the period of slavery, however, vodou created the environment for people to meet, and share cultural ideals and political alliances. Despite being banned, this did not stop people from worshipping in secret. This act of rebellion provided the foundation for bigger and more open resistance.

Fatiman and Dutty Boukman officiated the secret ceremony which was not only a religious ritual but also a meeting to mobilise the enslaved masses from plantations across the country. They strategised on destroying the “sugar plantation economy and outlined the terms of their liberation”. The ceremony and other vodou rituals that involved both men and women were key in bringing racial solidarity between the diverse population in Haiti that included the enslaved, creoles, Africans, free people of colour and Maroons. “These sacred rituals were spaces for enslaved people to come together and practise their religious and sacred practices from whatever fragments of memory that they could put together or reformulate in this new space.” Eddins also mentions that the shared experience of being commodified as slaves and racialised as black was also part of the radicalisation process.

While history remembers and honours the male heroes, the female freedom fighters are less well known (Credit: Courtesy of the artist, Francois Cauvin)

Independence came at a crippling cost, and the country is still suffering the effects of the revolution. However, it’s important to acknowledge that the brave overthrowing of slavery and the creation of an independent Haiti was a joint victory between men and women. And while many sources exist focusing on the male figures of the Haitian Revolution, recent efforts have been made by historians, scholars, activists, writers and others to locate women’s stories of the revolution, and bring them to light – not only for their contributions to the cause but also to understand their lived experiences.