Jamaica Gleaner Editorial | Transcendental Ramphal

Often, eulogies inflate the virtues and achievements of their subjects, even of great men.

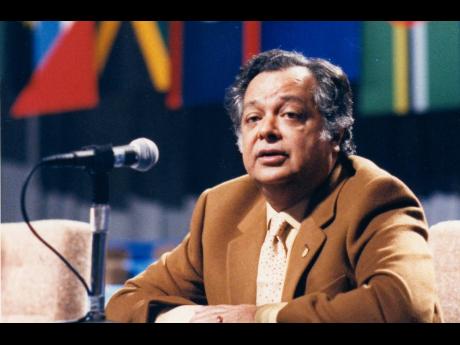

Hardly can such a claim be made about Shridath ‘Sonny’ Ramphal, a Guyanese by birth, West Indian by inclination, and a committed global citizen, who died on Friday, a month shy of his 97th birthday.

Indeed, the long list of honours, including Jamaica’s prestigious Order of Merit (OM), bestowed on Sir Shridath by countries and institutions, during his lifetime, speak more eloquently to his accomplishments and the esteem in which he was held than anything that might be said about him in his death.

Yet, three statements, one before he died, but now resurrected, are profound summations of, and testaments to, Sir Shridath’s life and accomplishments.

One was by Nelson Mandela, the South African leader, in 1990 during a visit in London, shortly after being released, after 27 years in prison, for opposing his country’s system of Apartheid and white-minority rule.

“He is one of those men who have become famous because in their fight for justice, they have chosen the world as their theatre,” Mr Mandela said.

The second is contained in Barbadian Prime Minister Mia Mottley’s eulogy to Mr Ramphal.

“As a region,” Miss Mottley said, “We have produced many outstanding leaders in a multitude of areas – great men who made it clear that we would never be confined by size.

“But there is a smaller group that stands at the pinnacle of Caribbean greatness, people whose lifetime of labour for the betterment of the West Indian people compelled us to view them not by the country of their birth, but by their efforts to make us recognise our oneness and honour our oneness.”

Finally, as P. J. Patterson, the former Jamaican prime minister, put it, “Sir Shridath was not just a leader; he was a beacon for the developing world, championing causes that range from decolonisation to economic development.”

UNFORTUNATE

This country’s award of the OM to Sir Shridath notwithstanding, it is unfortunate how little Jamaicans seem to know, or appear to care, in the island’s role in providing some of the spark that helped to light Sir Shridath’s beacon, to which Mr Patterson referred.

Like many of his generation, Sonny Ramphal’s sojourn in post-war England to study law honed his sense of being a West Indian.

Or, as Sir Shridath described in an introduction to his CV on his website: “I became a West Indian in London …But my West Indianness became all-consuming.”

Significantly, that identity was sharpened by the influence of Norman Manley, a Jamaican political leader and national hero.

In the same introduction, Sir Shridath writes, “In 1950 Norman Manley visited London and spoke to West Indian students at LSE (London School of Economics). I was wholly captivated and confirmed my notion that the furtherance of West Indian federalism has to be the central goal of my life.”

Eventually, the young Ramphal returned to what was then British Guiana as a legal draughtsman and then solicitor general, before being recruited by the renowned Jamaican jurist, Harvey DaCosta, as his deputy as attorney general of the West Indies Federation.

When the federation collapsed, Sir Shridath joined Mr DaCosta’s new law firm in Jamaica. Indeed, it is from Kingston that the Guyanese leader, Forbes Burnham, enticed Sir Shridath to join his administration, in which he served with integrity and distinction in several positions, especially as foreign minister.

In 1975, Sir Shridath was elected unopposed as the secretary general (SG) of the Commonwealth. He held the post for 15 years, the longest by an SG to date, and at a period when the Commonwealth was perhaps at its most potent.

ESSENTIAL ARCHITECT

In many respects, Shridath Ramphal was the essential architect, and embodiment, of the modern Commonwealth, which he made into a moral voice against apartheid, anti-colonialism, hunger and poverty, and strangling Third World debt. Indeed, within the movement, no voice, except perhaps Jamaica’s Michael Manley’s, no one spoke longer, louder or more passionately than he against South Africa’s apartheid and white-minority rule in the rest of southern Africa.

In the Caribbean, in the face of the collapse of the Federation, he remained a tireless advocate for regional integration.

He understood deeply that contrary to Eric Williams’ “spurious arithmetic”, declared after Jamaica’s withdrawal from the Federation, that “one from 10 leaves nought”, that the combination of the region’s parts was likely to be greater than their arithmetic sum.

The Caribbean Community’s transition to a single market and economy remains a work in progress. Every inch of progress made is a credit to the vision and will of people like Shridath Ramphal, who, for three-quarters of a century, up to his death, stuck to the mission and still had time and energy attempting to make the world a better place for everyone who inhabits it.

It would be a fitting monument to Sir Shridath’s memory for CARICOM to complete the work on the CSME, especially the right of free movement in the region for all CARICOM citizens, as envisioned by the Revised Treaty of Chaguaramas.

Further, even ahead of their next formal summit, CARICOM leaders should commission work in other tangible ways of honouring Sir Shridath.