By Nigel Westmaas

(This is a summarised version of a paper delivered at the Guyana Institute of Historical Research in June 2013 to mark the 250th anniversary of the 1763 revolution. At the time of the presentation, Marjoleine Kars’ groundbreaking study (Blood on the River) of the 1763 event had not yet been published, so the paper does not reflect some of the new research on the event.)

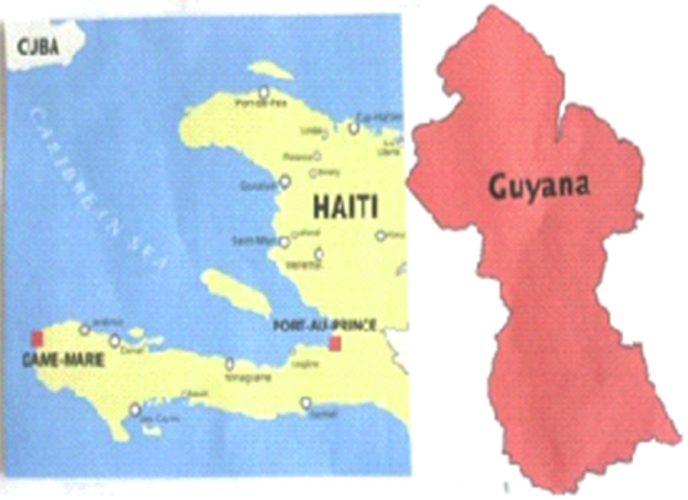

This article focuses on the Kofi 1763-64 revolution in Berbice and the Haitian revolution of 1791-1804. Utilising available mainstream research, it compares and contrasts the context, course, leadership, and outcomes and impact of both slave uprisings and revolutions.

The methodology of comparative history is central to this analysis and involves different historical events, or processes to identify patterns, similarities, and differences. It is a valuable tool for understanding how specific factors—such as economic conditions, social structures, or leadership—may influence the course and outcome of historical events. However, it is important to acknowledge that evaluating different events is inherently challenging due to varying perspectives, time periods, sociological and political contexts, and the general imprecision involved.

The assessment of the “success” or “failure” of both Berbice and Haiti is offered primarily through the specific lens of state power. In other words, the comparison is framed around the concept of the nation-state, focusing on the overthrow or challenge to the authority of European colonial powers. This perspective is important because the notion of “success” could also be attributed to the many Maroon societies that established their own spaces and governance within the borders of colonial states—such as those in Jamaica, St Lucia, Guyana, Suriname, and the nearly century-long revolt in Palmares, Brazil (1605-1694 approx).

In 1763, production under the Dutch, in a Berbice territory that was 17,900 square miles, was relatively small compared to Haiti (St Domingue). Berbice held approximately 85 private and company plantations winding all the way down the Berbice River in what Anna Benjamin termed “a more intimate, personal river… snaking its way ribbon like through the bush covered banks”. In terms of production, the local economy was relatively stable at the time of the revolt. Alvin Thompson noted for example that “a particularly good harvest had been reaped in 1755, and 1763 seemed to hold promise of another.” In 1762, the approximate population of Berbice numbered, according to official records, (and excluding free Amerindians), 346 whites, 244 Amerindian slaves and 4,000 black enslaved.

By contrast, Haiti at the onset of its revolution in 1791 was the largest producer of sugar in the world. In 1789, according to one source “some 4,100 ships were registered leaving and entering the country’s ports.” Production levels in Haiti were also astronomical: “sugar, coffee, cotton, indigo and cocoa were produced on 8,500 plantations”, according to the source, and there were approximately 500,000 enslaved on the island.

Moments in the 1763 uprising

Twenty-eight years before the Haitian revolution, Kofi’s men and women planned, organised and attacked Dutch planter and colonial interests in Berbice. In the long history of slave revolts in the western hemisphere, Berbice was the only example of an enslaved revolt that held out for a period of a year plus. It is also true that 1763 pales in terms of size (that is the number of insurgents active in the respective rebellion) with other major enslaved revolts including the substantial Jamaican slave revolts of 1760 (Tacky’s revolt) and the massive insurrection of 20,000 slaves in the Baptist revolt of 1831; and of course the largest Guianese slave revolt, the Demerara revolt of 1823. But, as Eusi Kwayana wrote in 1966: “West Indian activities cannot afford to pay obeisance to quantity…. Numbers, then, are not of the first importance. It is sufficient that there is new historical precedent. A small number of human agents in a human drama can conceivably do something that has not taken place before, something astonishing to informed observers. This was the case with 1763.”

There are several main historians of the 1763 Berbice revolt including Anna Benjamin, Alvin Thompson and Winston McGowan and their collective narrative of the Berbice revolt coincides in some broad areas. After the launch of the Kofi revolt on February 27, 1763, the revolution was consolidated by mid-March and the rebels had driven the colonists almost completely out of the colony. The first major battle of the uprising was at Plantation Peereboom where the Dutch were besieged by Kofi’s forces. By early March, other plantations were abandoned and the Dutch flotilla fled in utter pandemonium to other plantations. There was a major attack on Dageraad on May 16, 1763. Everywhere there was widespread panic among white planters and other colonists. Van Hoogenheim’s diary records “shouting and screaming” and the “woeful lamentation and consternation” as people heard of the approach of the insurgents. Many jumped into the river in panic. By the end of March, the governor managed to re-establish his forces at Dageraad as troops from Suriname arrived. There was a large five-hour battle on May 13 of 2,000 plus enslaved on Dageraad. In late May, a ship time report of the insurrection reached the Netherlands and Dutch forces were sent arriving in Berbice by November – December 1763. Negotiation and correspondence between van Hoogenheim and Kofi on tactical and strategic possibilities lasted for several months and about eight letters in all were dispatched by the two antagonists. Among the negotiating items at various stages was the possibility of power sharing, territorial division and/or the total removal of the Dutch. But the negotiations gave the colonial order crucial time. Indeed, at one point Kofi called off an attack after receiving a letter. By February 1764 the revolution was all but over but some rebel leaders persisted. One noted example was Fortuijn, a remarkable rebel leader from the Canje area who held out until June of 1764 and died by torture without flinching.

Convenient phases in the Haitian Revolution

In Haiti’s case, the complexity and enormity of the revolution again allows for only a brief summary. For Haiti, we can conveniently establish five phases for the course of its revolution.

The first phase was between 1791 and 1793 when on August 14, 1791, a rebellion broke out in Le Cap led by vodou priest Boukman. Many white planters and families fled. Thousands of the enslaved were killed as were planters and their supporters.

In the second general phase between 1793-1798 Britain and Spain declared war on France after the execution of Louis 16th. Fear of enslaved revolts local and global forced the British hand and there was an invasion of Haiti. White refugees and planters fled to North America – Philadelphia and Charleston. British and French troops were welcomed by planters, and they conspired to restore slavery on the island. Toussaint L’Ouverture emerged at this point as a leader out of the masses.

The third phase, between 1798-1802, marked the consolidation of Toussaint’s power. Unity between Toussaint (North and West) and Rigaud (South) drove out the British, but tensions soon arose, leading to a regional struggle. By mid-1800, Toussaint ruled Saint-Domingue (Haiti) and travelled extensively to maintain control. He reintroduced plantation work for ex-enslaved people and welcomed back white planters and advisors. When General Moise, Toussaint’s nephew, revolted against this policy, Toussaint had him and hundreds executed. Meanwhile, Napoleon Bonaparte came to power in France (1799), setting the stage for conflict. In 1801, when Napoleon declared himself emperor, Toussaint issued a new constitution, maintaining loyalty to France with the condition that slavery must end.

The fourth phase we can call the War of Independence between 1802-1803. In this period Napoleon’s brother-in-law General Le Clerc landed 10,000 troops in Saint-Domingue in February 1802, the largest overseas armada of troops sent abroad up to that time. Resistance was initially light; several black generals surrendered but Toussaint, Christophe and Dessalines fought on in rearguard actions with the support of rural blacks. Toussaint was eventually captured through deceit and taken to France in chains. Dessalines, a formidable military tactician and a harsh, controversial commander with a strategy of total liberation, continued his fight. Formerly a field slave, his back bore the scars of 360 whip marks. Le Clerc died of yellow fever in this period but in 1802, French general Rochambeau (personally sent by Napoleon) waged a war of genocide against the black population. But this also backfired and served instead to unite the Haitian people. Ultimately, 100,000 European troops fell on Haitian soil.

The fifth and final phase involved victory and Independence. On Jan 1, 1804 Dessalines declared Saint-Domingue independent and named it Haiti. All whites were forbidden to own land in Haiti. Having destroyed the wealthiest planter class in the New World – and defeated the armies of France, England and Spain – the Haitians tried to restore the economy and build a free republic. Without going into detail we see in the case of Haiti the scale of the revolution in contrast to Berbice. We should note that in both the Berbice and Haitian revolutions there were clusters of leaders and defining leadership figures with contrasting personalities and tactics in each case. There were Toussaint and Kofi; Dessalines and Akara; Moises and Atta and Fortuijn. And as with all leaders and leadership in momentous events there was treachery and rivalry, military geniuses and poor commanders. Again on a comparative note, Alvin Thompson stated that the African forces of Berbice were estimated by “their antagonists at between 2,000 and 2,500 men”. The military forces at the disposal of Toussaint ran into the tens of thousands and of course the Haitians were fighting three European armies. And even though nothing could rival the troops dispatched by the French to Haiti, we should note in comparative perspective that the Dutch sent “the largest expeditionary force ever to set sail for a Dutch colony …” with a total of 660 army volunteers to Berbice.

The fifth and final phase involved victory and Independence. On Jan 1, 1804 Dessalines declared Saint-Domingue independent and named it Haiti. All whites were forbidden to own land in Haiti. Having destroyed the wealthiest planter class in the New World – and defeated the armies of France, England and Spain – the Haitians tried to restore the economy and build a free republic. Without going into detail we see in the case of Haiti the scale of the revolution in contrast to Berbice. We should note that in both the Berbice and Haitian revolutions there were clusters of leaders and defining leadership figures with contrasting personalities and tactics in each case. There were Toussaint and Kofi; Dessalines and Akara; Moises and Atta and Fortuijn. And as with all leaders and leadership in momentous events there was treachery and rivalry, military geniuses and poor commanders. Again on a comparative note, Alvin Thompson stated that the African forces of Berbice were estimated by “their antagonists at between 2,000 and 2,500 men”. The military forces at the disposal of Toussaint ran into the tens of thousands and of course the Haitians were fighting three European armies. And even though nothing could rival the troops dispatched by the French to Haiti, we should note in comparative perspective that the Dutch sent “the largest expeditionary force ever to set sail for a Dutch colony …” with a total of 660 army volunteers to Berbice.

What general conclusions can we draw from the course of events in both of these remarkable revolutions?

First, both revolutions occurred at the height of the Atlantic slave trade. Second, they both disrupted and weakened European and American capital, as well as the slave trade and slavery in general. Haiti’s revolution also led to the collapse of Napoleon’s grand design for the American colonies, culminating in France’s sale of Louisiana to the United States in 1803 following Haiti’s defeat of Napoleon.

In the wake of the revolution the new republic, Haiti provided military aid to Simon Bolivar and Latin American republics with arms in their anti-colonial fight. Other slave rebellions in the Atlantic and the Americas were influenced by word of mouth via newspapers and ship ports. Also, on account of the dramatic fall in sugar exports after Haiti’s victory and subsequent isolation by the big powers, Cuban sugar benefited enormously from the punitive economic isolation of Haiti. The global isolation of the revolution was crucial. Haiti became a leper state, but the country bravely continued its mission of freedom for enslaved people everywhere and its constitutional clauses and articles opened possibilities of extending freedom and citizenship to the enslaved from other plantation societies. For instance, in 1817, Article 44 of the Haitian constitution allowed three enslaved Jamaican mariners who had escaped, to land on Haitian soil to freedom much to the chagrin of the Jamaican planters who tried unsuccessfully to negotiate their return with President Petion.

In the case of Berbice, the revolution resulted in the depopulation of the area; the white population was reduced by half. The heavy cost on Dutch expenditure – mainly for the cost of expeditions drained the colony and Holland thereby weakening the Dutch empire overall. After 1763 there was a temporary disruption of open slave resistance in the area. The prison population grew significantly with incarceration rates of 2,500 and other punishments made the situation very grave. And yet by the end of the 18th century, resistance continued unabated and the maroon activity of the 1790s in Guiana was testimony to this. The governor of Berbice at the centre of the revolt, van Hoogenheim, was replaced.

This is just a summary of two monumental events, but what stood out in both revolts was the brave tactical and strategic vision of Africans under slavery and the severe odds they faced in Guiana, Haiti, and the Americas in general. It is a magnificent testimony to the human spirit that, despite the immense challenges of maintaining secrecy, discipline, and strategy—and with the full awareness that their chances of survival were slim—the Africans in Berbice and Haiti succeeded to the extent they did, despite so much being stacked against them. It is essential to ignite the history of the Berbice Revolution in the minds of young people, from kindergarten to university.

The 1763 Berbice Revolution deserves prideful celebration, especially as it predates and compares to the Haitian Revolution, the most permanent of them all.