By Baytoram Ramharack

Political biographies of prominent Guyanese are rare. The publication of the biography of Janet Jagan written by Professor Emerita Patricia Mohammed is a welcome addition to Guyanese historiography. Whatever one might opine about Janet Jagan, her political tenure in Guyana is marked by controversy, partly because not much is publicly known about her personal background and what sustained her political activism for more than 60 years. This book is an attempt to fill that void by interrogating key moments of Janet’s life experiences. The author undertakes this task by venturing well beyond Janet Jagan’s political activism and argues the case for a complex personality – an agent of change thrust into an unfamiliar political and cultural space, who together with her husband, was driven by a mission to improve the quality of life for Guyanese. Perusing the narrative, one cannot fail to notice the diverse opinions ascertained from oral interviews – the core of the author’s investigative “methodology” – and the simplicity of language by which the biography is presented. This book amounts to more than a bird’s eye view of the life and legacy of Janet Jagan.

Readers should be alerted to two caveats regarding this non-fictional publication. First, it is written by Patricia Mohammed, a Trinidadian who specializes in the study of feminist theory and gender (in)equality. Her background endows her with the analytical tools to competently examine Janet’s role as a female agent of change, while minimizing the tendencies for injecting personal biases. Not oblivious to this challenge, the author treads a fine line by confessing that her work “weighs on the side of compassion” but seeks to avoid the “ethnic or political discourses that force people to choose sides.” Second, the biography is commissioned by friends and families of the Jagans, who, understandably, are vested in the preservation of Janet’s legacy. This relationship provided the author with access to information not generally available in the public domain, but readers should not expect a critical assessment of Janet’s work. Arguably, the author has achieved her goal of delivering “a meaningful tribute to Janet Jagan.”

Readers should be alerted to two caveats regarding this non-fictional publication. First, it is written by Patricia Mohammed, a Trinidadian who specializes in the study of feminist theory and gender (in)equality. Her background endows her with the analytical tools to competently examine Janet’s role as a female agent of change, while minimizing the tendencies for injecting personal biases. Not oblivious to this challenge, the author treads a fine line by confessing that her work “weighs on the side of compassion” but seeks to avoid the “ethnic or political discourses that force people to choose sides.” Second, the biography is commissioned by friends and families of the Jagans, who, understandably, are vested in the preservation of Janet’s legacy. This relationship provided the author with access to information not generally available in the public domain, but readers should not expect a critical assessment of Janet’s work. Arguably, the author has achieved her goal of delivering “a meaningful tribute to Janet Jagan.”

The book highlights several broad strands of Janet Jagan’s life and the issues that occupied her attention in Guyana. The narrative questioned the validity of some traditionally held beliefs by critics of the People’s Progressive Party (PPP), such as Janet’s indifference with Cheddi Jagan on matters of “strategies and tactics and ideological issues,” her role in indoctrinating Cheddi with Marxist ideology, and her own “dogmatic Marxist-Leninist approach to development,” to name a few. The narrative also highlights several long-held assumptions about Janet, including her effective organizational skills, her role as archivist for the PPP, and as a person who maintained fraternal ties with leftist radicals around the world, such as Billy Strachan (Communist Party of Great Britain), Ahmed Ben Bella (exiled Algerian president), Nazim Hikmet (exiled Turkish poet).

Readers are reminded about Janet’s talent for poetry writing, her ability to compose short stories, as well as her interest in environmental preservation. The narrative also speaks to her role in uplifting the status of women in British Guiana, her frugality and her generosity.

The book praises Janet’s journalistic drive and her impassioned embrace of the arts and artists of Guyana. It was Janet who boosted Martin Carter’s career by publishing his early poems in Thunder (as editor), she supported Helen Taitt and the School of Guyana Ballet, patronized Castellani House as a National Gallery, supported the Roth Museum of Anthropology, and she donated rare photographs to the National Trust of Guyana. Books from her personal collection were gifted to the National Library, and it was Janet Jagan who created the Museum of African Heritage.

Professors Ramabai Espinet and David Dabydeen (who, along with Jeremy Poynting assisted with publication of her writings) speculated that Janet’s political activism may have been influenced by Edna Manley (of Jamaica), as well as Phyllis Alfrey (of Dominica), both of whom were “phenotypically white, socialist.” Janet’s love and support for the arts may have been attributed to her “Jewish intellectual culture.” Western fiction and non-fiction works, the classics and short stories of Russian literary artists like Anton Chekhov, as well as the Georgetown creole community played a significant role in influencing her philosophical thoughts and literary efforts. Nonetheless, as a patron of the arts, one is hard pressed to conclude from the author’s narrative that Janet Jagan shared an unburdened appreciation for and interest in the cultural expressions of her largely Indian supporters.

The 15 chapters dedicated to an understanding of Janet Jagan’s contributions to Guyana reveal the personality of a person not cut from the same social and cultural fabric of the two political giants – Cheddi Jagan and Forbes Burnham. Yet, in a modern nation born out of a rejection of European colonialism, an American born woman would occupy the highest leadership position in Guyana. Her ascension came with a price. As the author notes, the most obvious reason for Janet’s accomplishment stemmed from living in the political world fashioned by her Indian Guyanese husband. Perhaps more important though is the fact that Janet commanded the respect of the party’s core leadership. She remained the de facto organizer, administrator and protector of the PPP from its inception to her demise. Her imposing authority, acquired reputation and organizational ability proved pivotal in 1997, following the untimely death of her charismatic husband who had outlived the Cold War, and his political nemesis, Forbes Burnham.

A crucial test surfaced in 1997 when the party had to contend with internal factions. The presidential contenders for leadership were Janet Jagan, Clement Rohee, Bharrat Jagdeo and Ralph Ramkaran. Cheddi had apparently anointed Janet as his successor, by association, if not by public endorsement. Jagdeo and Rohee declined to challenge Janet, but Ramkarran had to contend with a “vulgar and organized demonization” of his character and integrity from comrades within his own party. Despite Janet’s hesitancy in assuming the mantle of leadership due to “old age, health issues, whiteness, and foreign born” the party cadres hitched their wagons around her candidacy. She won an overwhelming victory for the Presidency (presumably due to sympathy votes and the Jagan persona).

Ironically, her electoral victory was pyrrhic. Her victory was greeted with street protests and targeted violence against Indian supporters of the PPP, led by Africans and the PNC. PPP leaders, including Janet Jagan, remain perplexed as to the underlying causes for the vitriolic assault on what they considered to be a historical achievement – the first female presidency of Guyana. The rebellion led by the opposition was not simply a reaction to Janet Jagan’s perfidious defiance of throwing the court injunction documents over her shoulders at State House on December 19, 1997 “in an unpresidential fit of pique.” The author invokes a quotation from Linden Lewis, a Guyanese professor at Bucknell University, who wrote a biography of Forbes Burnham, in order to explain the politics behind the anti-Janet Jagan backlash: “I had a neutral position …initially, as she had earned the right by virtue of her longevity in the political landscape. But then I backed off…I don’t care how long she stayed in Guyana, she’s an American. I can’t stay here long enough to be president of the United States. By virtue of birth, I am eliminated from that possibility, and to give her that position to me is really problematic, so I don’t come to this on account of race, I do it on account of political principle, and the question of nationalism and sovereignty and all those things. The only thing that mitigates that in a way is that her citizenship in the United States was revoked…”

In 1997, after 54 years of residing in Guyana, in a moment of self-denial, and perhaps taking comfort in the fact that her support among Indians was unshakable, Janet insisted that “people do not see white when they look at me.”

Professor Patricia Mohammed is neither a trained historian nor a political scientist. Not surprisingly, she surrendered to the litany of interviewees who monopolized the storytelling of her main character. Her study, however, fell short of addressing some crucial areas in Janet Jagan’s political tenure. For one, Janet did not merely function in the political shadows of her husband; she was an integral partner – a comrade in arms – who envisioned a decaying and exploitative capitalist system giving way to a new economic model engineered to promote respect for human dignity and equality. Unlike her husband, Janet did not wear her political ideology on her sleeves, but readers are not exposed to an interrogation of Janet’s consideration of the consequences of the policies adopted by her party, particularly when discussions of such issues arose during the post-Cold War era. Was this a case where a more pragmatic Cheddi Jagan was “Gorbachev before Gorbachev” but Janet, who was opposed to the PPP alliance with the “Civic,” remained, as a member of the old guard, more interested in preserving the party’s original image and protecting her, and the party’s orthodox Marxist ideology?

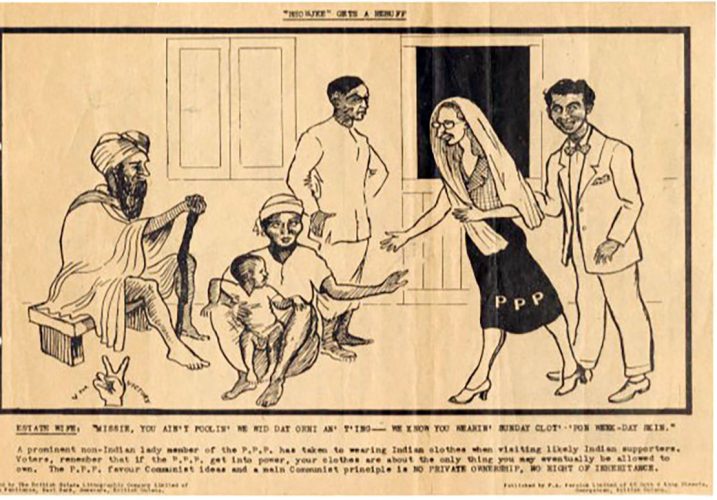

Anti-Janet Jagan caricature mocking her Indian clothing

Most unfortunate, at least for this reader, is an unexpected, but glaring omission of a discussion from the narrative of Janet Jagan’s views on the racial/ethnic problem, which defined Indian – African relations. The “race problem” was certainly not oblivious to Janet. It was an enduring problem for most of her political career, and she was certainly conscious of her own “whiteness” being a minority living in a racially divided society, as she intimated in an interview with David Dabydeen.

Chapter Eleven, boldly captioned “The Blue-Eyed Bhowgie of Guyana,” conveys a specious impression that the divisive issue of race/ethnicity would suffice and be confronted in the narrative. Instead, the focus quickly meandered into an exposé on the personal lives and familial relationships of the Jagans. However, as the author correctly observed, “bhowgie” is a term of endearment, bestowed upon Janet Jagan because of Indian innocence and naivete. The use of “blue-eyed” as a descriptor was a reference to Janet’s physical character, but it was also an indication of her being considered as a political saviour (primarily by Indians).

Janet Jagan resigned her portfolio as Minister of Home Affairs (under British rule) in 1964, at a crucial time when the country was faced with serious political and racial violence between Africans and Indians. Yet, she never attempted to confront this dilemma by aggressively advocating for structural changes in the institutions of power or sought to address the security concerns of both Africans and Indians when her party had an opportunity to do so.

Sydney King (Eusi Kwayana) said in 1957 that Janet Jagan suffered from the “Lady Macbeth complex.” In hindsight, this was an unfair characterization because Janet Jagan was more than a cheerleader during her husband’s political career. In reality, though, Janet Jagan represented a political anomaly, and a rarity where a foreign-born individual could become the leader of a country defined by a cultural mosaic and history far removed from her experience in Chicago. Clearly, the author has recognized that Janet Jagan has earned a permanent niche as a shaper of modern Guyanese political history and that Janet was more than an inconsequential appendage to the legacy of Cheddi Jagan. For anyone interested in modern Guyanese historiography, which would undoubtedly include the legacy of Janet Jagan, reading this book should be a good place to begin that journey.

Baytoram Ramharack teaches history and politics at Nassau Community College (New York).