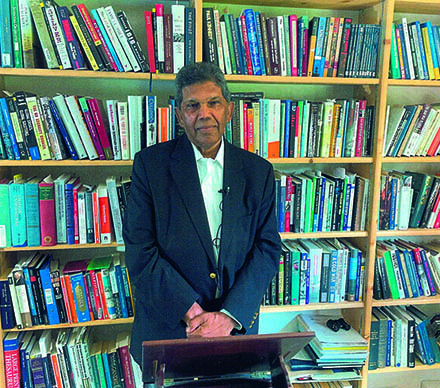

By Dr Bertrand Ramcharan

Honourable Members of the Peace Seminar of Columbia University,

It is a distinct honour to address you at this Peace Seminar, which I myself chaired at one stage, and to which I last spoke after I came off the peace-making, peacekeeping, peacebuilding, and humanitarian processes as Director of the International Conference on the Former Yugoslavia for nearly four years. We meet at a time of great challenges for the UN, when climate change endangers the world, wars are raging in several parts of the world, humanitarian and human rights crises abound, the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals is stalled, and the peoples of the UN are asking about its relevance and its future.

I had the privilege of serving the United Nations for three and a half decades, commencing at entry level and leaving at the level of Under-Secretary-General. I have served in peace and during war, and was given the rare opportunity to serve with love – to borrow a phrase from one of my distinguished compatriots in Guyana. I have probably had one of the most diversified careers of any UN official in the history of the world organization, touching on all three foundational areas of the UN, peace, development, and human rights, and I shall endeavour in these reflections to share some insights from my engagements. I shall begin with the area of peace.

Peace

For five years I was Chief of the speechwriting service of the UN Secretary-General and wrote the first draft of Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali’s Agenda for Peace (1992), which was devoted to preventive diplomacy, peacemaking, peacekeeping, and peace enforcement. I also wrote a fair bit about preventive diplomacy at the United Nations, subsequently authoring two books on this subject. I followed up on the issue of preventive diplomacy and preventive strategies when I performed the functions of UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. I have since written a book, Preventive Human Rights Strategies.

For three and a half years I was Director of the International Conference on the Former Yugoslavia and was involved extensively in the peace negotiations, in peacekeeping, peacebuilding, peace enforcement, and humanitarian operations. For three years I was Director in the UN Political Department dealing with African conflicts. While in the Office of High Commissioner for Human Rights I conducted a mission to the Ivory Coast during the midst of the war in that country, submitting a report on my visit to the UN Security Council. I did a mission for Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon to Georgia a week before the Russo-Georgia war. And I have been part of a UN team that visited prisoner of war camps in Iran and Iraq during the war between those two countries. I have come to the following reflections on the role of the United Nations in the area of the maintenance of international peace and security:

Preventive Diplomacy: The UN should do its utmost to foster national prevention systems in every country. This idea was advanced by former Secretary-General Kofi Annan and is now highlighted by Secretary-General Antonio Guterres. In addition, the UN could establish more regional and sub-regional centres promoting preventive diplomacy. It currently has four such centres, three in Africa and one in Central Asia.

Peacemaking: Peacemaking by the UN is influenced by the distribution of power on the ground and by the attitudes of external powers, especially great powers. Parties with the will to fight and the means to fight will fight, unless a more powerful source imposes itself on them. That more powerful source is usually a great power, rarely the UN. There are situations that the UN can do very little about and one should recognize this. The UN should endeavour to contribute in situations where its efforts can be meaningful.

Peacekeeping: UN peacekeeping has been, and remains, a valuable asset of the UN. In the future, the UN could concentrate more on the deployment of international observers. The UN should rarely be involved in peace enforcement. It is an organization of peace, not of war-fighting.

Humanitarian operations: The UN renders invaluable service to millions of people in need, but UN humanitarian operations are invariably under-funded. In the Yugoslav conflicts we saw that humanitarian aid was diverted by warring functions for military purposes. As a member of an international inquiry panel into the human rights situation in Darfur, I could see how valiantly UN humanitarian personnel were endeavouring to bring aid to people desperately in need. Alas, this desperate situation continues in our time, as we gather here.

Development

I am convinced that the UN Sustainable Development Goals cannot be fully achieved without efficient and fair governance in every country and without universal respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. Development and human rights need to go hand in hand.

I could see this as member of an international Commission of Inquiry into the situation in Zimbabwe, then under President Robert Mugabe.

I am of the view that the right to development, in the elaboration of which I have participated and followed from the inception, needs more attention to be given to the national implementation of the right to development. I have written about this in a monograph published by the University of Cape Town.

Human Rights

Human rights work needs both the seed-planter and the fire brigade. The gardener plants the seeds of future protection of human rights. The fire brigade endeavours to put out the fires of gross violations of human rights. Without the efforts of the gardener, one cannot prevent future fires of gross violations.

The most important seed-planting effort that the UN can undertake is to work with countries on the establishment or enhancement of adequate and effective national human rights protection systems. The Universal Periodic Review operated by the UN Human Rights Council can help in this process. I have just published a Global Handbook on National Human Rights Protection Systems which explores how this can be done.

Another insight I would like to share is that the achievement of universal respect for human rights requires the vigorous participation of civil society organizations. I have mapped this out in a recent publication, The Protection Roles of Human Rights NGOs. It contains chapters written by NGO leaders on problems encountered on the ground in numerous societies across the world.

A key need, in my view, is that we must do our utmost to promote human rights education across all settings. This is why, serving as High Commissioner, I called for a UN Declaration on Human Rights Education, which was subsequently elaborated and then adopted by the UN General Assembly.

The UN of the Future

As we meet here, the UN is assembling for its Summit of the Future, at which it will adopt a Pact for the Future. I shared such a moment when I wrote the first draft of Agenda for Peace in 1992 some three decades ago. I tend to the view that:

The UN operates best through incremental approaches, with carefully selected and realizable goals.

The structure of governance in UN Member States influences the achievement of national and international goals. The authoritative Economist Intelligence Unit publishes an annual report on the state of governance in the world, which shows that the overwhelming majority of UN Member States are not governed by democracies. What does this say about the governance of the UN, its selection of policy goals, and their implementation nationally. I leave this to you to ponder. In Commonwealth law there is a maxim of equity: “He or she who comes to equity must come with clean hands.”

The UN of the future will require wise leadership and careful diplomacy in a world of contestation among the great powers.